Why Bill Maher is Right About Marijuana – But Also Terribly Wrong.

Posted on | February 25, 2015 | 2 Comments

Mike Magee

Bill Maher prides himself on logic and clarity, and of course, in-your-face, biting humor. This is on full display during his “New Rules” segment, with which he closes each show. He is especially well known for his personal and professional advocacy for the legalization of marijuana. His major points are that the substance is relatively harmless and that the criminalization of the substance has done far more harm than good, especially for minorities.

As he said last week, (while excoriating Ted Cruz and Jeb Bush, both of whom have admitted using the substance in the past, but are opposed to legalizing it), “Obama should acknowledge that putting people in jail for nonviolent drug offenses was a giant mistake in the first place, and then he should use the power of the presidential pardon and free them all.” And, with special reference to the youthful indiscretions of the Bush brothers, “We should at least be honest with our kids and tell them the truth about drug laws in this country. Kids, if you’re gonna experiment, make absolutely certain that beforehand your parents are white and well-connected.”

And, of course, Maher is right. The “Drug War” has been a disaster, and it is patently racist. Just consider the record in the largest cities on the East and West coast. In New York, during Mayor Bloomberg’s tenure, from 2002 to 2012, 1 million police hours were expended making 400,000 marijuana possession arrests. And who gets arrested? That’s well-documented – it’s primarily blacks and hispanics, caught up in “stop and frisk”.

New York Times columnist Charles Blow went after the city’s Democratic politicians on the “how it happens” piece. As he said, “The war on drugs in this country has become a war focused on marijuana, one being waged primarily against minorities and promoted, fueled, and financed primarily by Democratic politicians. Young police officers are funneled into low income black and Spanish neighborhoods where they are encouraged to aggressively stop and frisk young men. And if you look for something you’ll find it. So they find some of these young people with small amounts of drugs. Then these young people are arrested. The officers will get experience processing arrests and will likely get to file overtime… And the police chiefs will get a measure of productivity from their officers. The young men who were arrested are simply pawns.… No one knows all the repercussions of legalizing marijuana but it is clear that criminalizing it has made it a life ruining racial weapon.”

The practice is mirrored exactly on the West coast. Even though young whites have been shown to use marijuana at higher rates than blacks, LA police officers in the past 20 years have arrested blacks for marijuana possession at a population adjusted rate six times that of whites. How about other cities? San Diego – 6X disparity; Pasadena – 12.5 X disparity. In the state capital of Sacramento, the black population (14% of the total) accounts for over half of all marijuana arrests.

Now when you combine the targeting of minorities with the lack of legal resources to fight these arrests, you begin to understand how a minority that accounts for 13% of the population can be the source of more than 40% of all imprisoned Americans. Compare that with whites, who represent 64% of our population, but contribute only 39% of our prison population.

So Bill Maher is right about marijuana, but he’s also terribly wrong. Where he loses me is in glibly suggesting that weed is harmless, at least in comparison to other substances. On the surface, I’ve always known this to be untrue. After all, you’re breathing chemical-laden smoke deep into the bronchial tree. That can’t be good. Young active minds dulled and confused? That can’t be good. Operating motor equipment while impaired? That can’t be good.

Now a major study, published last month in Addiction magazine, under the auspices of the WHO, supports my biases with facts. The author, Wayne Hall, an addiction specialist at the University of Queensland in Australia, compared populations in 1993 and 2013. He focused on “two New Zealand birth cohort studies whose members lived through a historical period during which a large proportion used cannabis during adolescence and young adulthood; sufficient numbers of these had used cannabis often enough, and for long enough, to provide information about the adverse effects of regular and sustained cannabis use.” His results were in line with other recent cohort studies in Australia, Germany and the Netherlands .

Adverse effects of chronic use:

“Psychosocial outcomes:

Regular cannabis users can develop a dependence syndrome, the risks of which are around 1 in 10 of all cannabis users and 1 in 6 among those who start in adolescence.

Regular cannabis users double their risks of experiencing psychotic symptoms and disorders, especially if they have a personal or family history of psychotic disorders, and if they initiate cannabis use in their mid-teens.

Regular adolescent cannabis users have lower educational attainment than non-using peers.

Regular adolescent cannabis users are more likely to use other illicit drugs.

Regular cannabis use that begins in adolescence and continues throughout young adulthood appears to produce cognitive impairment but the mechanism and reversibility of the impairment is unclear.

Regular cannabis use in adolescence approximately doubles the risk of being diagnosed with schizophrenia or reporting psychotic symptoms in adulthood.

All these relationships have persisted after controlling for plausible confounders in well-designed studies, but some researchers still question whether adverse effects are related causally to regular cannabis use or explained by shared risk factors.

Physical health outcomes:

Regular cannabis smokers have higher risks of developing chronic bronchitis, but it is unclear if it impairs respiratory function.

Cannabis smoking by middle-aged adults probably increases the risks of myocardial infarction.”

That’s quite a list. Now Bill Maher is right on two counts: First, alcohol is worse. For example, as we’ve seen on multiple college campuses, you can die from alcohol intoxication. You can’t from marijuana. Second, marijuana possession has become the ultimate “Scarlet Letter” on the records of countless young black and hispanic males in the US. That’s why I’m for legalization.

But at the same time, Maher owes it to his faithful viewers, in his next “New Rules”, to point out that wide open use of marijuana by adolescents and young people is not without risk, and in fact, in Bill’s own words, “Is pretty f—ing stupid!”

For Health Commentary, I’m Mike Magee

Tags: bill maher > drug war > effects of mariquana > legalization of mariquana > Marijauan > New Rules > Real Time with Bill Maher

Precise But (Not Yet) Personal

Posted on | February 25, 2015 | 1 Comment

“President Obama’s new initiative to fund genetic sequencing could be a powerful tool for good in improving U.S. health care—but only if the medical establishment welcomes it.”

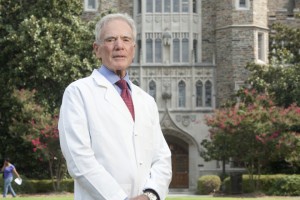

That’s the view of Duke Chancellor Emeritus, Ralph Snyderman, MD in a recent article in The American Interest.

In the article, he explains, “On January 30, 2015, President Obama announced a bold funding initiative to support the sequencing of the genomes of a million volunteers and correlate the data with clinical information to allow a better understanding of the roles genes play in health and disease. This information will boost precision or personalized medicine and allow appropriate therapeutics to be targeted to those who need them — that is, getting the right drug to the right person. This is in contrast to our current “one-size-fits-all” approach to care, where more than half of major drugs are ineffective or cause unwanted side effects, and drug expenditures are currently about $320 billion a year and rising. Replacing that approach with one designed to meet the precise needs of the patient would not only be better medicine, but also more cost-effective.” Read on…

Tags: Duke university > Personalized Medicine > Ralph Snyderman > The American Interest

If the “Homeland” is Safe, Is America Safe?

Posted on | February 13, 2015 | 1 Comment

Mike Magee

“Too often, road safety is treated as a transportation issue, not a public health issue, and road-traffic injuries are called accidents, though most could be prevented. As a result, many countries put far less effort into understanding and preventing road-traffic injuries than they do into understanding and preventing diseases that do less harm.”(1)

That’s what Dr. LEE Jong-wook, director-general of the World Health Organization,said in 2004. At the time it was estimated that 140,000 injuries occur on roads worldwide each day. Fifteen thousand people were disabled as a result, and 3,000 die.(1) In the year 2000, 1.26 million people were killed in roadway accidents, accounting for 25 percent of all deaths from injury that year.(2,3)

In 1990, roadway injuries were the ninth-leading cause of death and disability worldwide. But by 2020, that ranking is projected to shoot to number three, just behind ischemic heart disease and unipolar depression. The change in rank is based on a projection that roadway injuries will increase by 60 percent in 30 years if current trends continue.(4)

The burden of unsafe roads falls most heavily on the most vulnerable. But as we dramatically witnessed on February 4, 2015, in Valhalla, NY, the US is far from immune to this kind of preventable human carnage. In that accident, Metro North train # 659 crashed into a sports utility vehicle driven onto the rails by a 49 year old mother of three. The car was carried a thousand feet down the rails, and she died along with five passengers caught up in a fiery blaze in the lead train car.

An unfortunate “once in a million” transportation event in the most highly developed nation in the world? Apparently not, according to an investigative report in the New York Times last week. Their reporters took a road trip around the Metropolitan area to visit “the 10 crossings that the railroad administration’s accident-prediction algorithm deems the most likely sites for crashes in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut.”

Here’s the list including the number of railroad accidents at each site since 1975:

Elmwood Park,NJ – Midland Ave. (29 accidents)

Brentwood, LI – Washington Ave. Ave. (8 accidents)

Brentwood, LI – Fifth Ave. (8 accidents)

Central Islip, LI – Carlton Ave. (10 accidents)

Ramsey, NJ – Main Street (6 accidents)

Oceanside, LI – Atlantic Avenue (10 accidents)

Wyandanch, LI – 18th Street (6 accidents)

Bethpage, LI – Stewart Ave. (9 accidents)

Hackensack, NJ – Main Street (7 accidents)

Hackensack, NJ – Anderson Street (6 accidents)

Are these the exception rather than the rule across America. Yes and no. The worst location in the US is in Ashdown, Arkansas. They’ve had 19 accidents since 1975. But according to last week’s report, only 112 other sites have risk paradigm scores as high or higher than those listed above, but that’s out of 130,000 nationwide that were studied. Risk rises with the number and type of trains and autos, speed of crossing trains (some commuter trains cross at up to 80 mph), the presence of partially obstructed and “on-grade” track crossings, the absence of automated safety rails, and a history of faulty equipment.

Of course, all of these issues are correctable, and occasionally, after a tragedy, that is exactly what happens. Back in 1982, 9 teenagers riding in a minivan died in a fiery blaze in a train crash in Mineola, Long Island. In the aftermath and public outcry, citizens demanded a corrective response to the unsafe crossing. To their credit, the state did respond, but the creation of the new overpass took them an unbelievable 16 years and $85 million. Balance that against a Federal Highway Administration’s Section 130 program (for crossing improvements) annual allocation of $220 million for our entire nation.

As our Congress considers vast increases in Military and Homeland Security budgets in the name of “securing our homeland” (which are already, by all accounts, excessive), few appear to appreciate the irony. The reality is that “the homeland”, formerly known simply as America, each and every day, for each and every citizen who crosses rail, rides rail, uses roads and bridges, or rides and walks on spaces not safe or adequate for pedestrians, is not safe. And the reason has nothing to do with terrorists. It is a function of a Congress and a range of State Houses which neither lead nor represent this nation very well.

For Health Commentary, I’m Mike Magee.

References:

2.United Nations moves towards action on Road Traffic Safety following Bone and Joint Decade proposal. [press release]. Bone and Joint Decade. September 16, 2003.

3.Ahead of General Assembly, Annan urges commitment to Road Safety. [press release]. Bone and Joint Decade. September 9, 2003.

Tags: homeland security > infrastructure investment > railroad safety > railroad safety metropolitan ny > transportation safety

UNC’s Other “Dean Smith”: Colin “Tim” Thomas M.D.

Posted on | February 11, 2015 | Comments Off on UNC’s Other “Dean Smith”: Colin “Tim” Thomas M.D.

Tim Thomas with Mike and Trish Magee at 2008 UNC Distinguished Alumni Awards, Chapel Hill, NC.

This week the airwaves were filled with well-deserved reviews of the life and accomplishments of Dean Smith, the legendary basketball coach from the University of North Carolina “Tar Heels”. Loving basketball, and having introduced three of our four children to the game while in Chapel Hill from 1973 to 1978, I can well understand the universal admiration, not only for the coach, but also for the man.

But I didn’t want this moment to pass without paying tribute to a lesser known, but equally amazing UNC leader, of the same vintage as Dean Smith. His name was Colin Thomas, but his friends called him Tim. Of him, I wrote in Legends and Legacies: A Look Inside Four Decades of Surgery at The University of North Carolina At Chapel Hill, “Dr. Tim Thomas provided an excellent role model in medical education and showed me what a gentle man and a gentleman looked like in an academic setting.”

Tim died on September 2, 2014, in Chapel Hill at the age of 96. The official announcement of his death celebrated the fact that he was an “internationally recognized surgeon, revered medical educator, outstanding scholar, pioneering research scientist, and devoted Tar Heel”. All true.

But the fact that so many people, including myself, loved and admired him, likely had more to do with who he was than what he did. He was born in Iowa City in 1918, four years after my father. He was a farm boy, raised in the outdoors of Monticello, Iowa, and picked up the “patience, understanding, generosity and grace” that marked his personality from serving and working with horses and farm animals as a kid. Those same qualities were evident in the doctors in his family, and there were many – his father, Colin; his Aunt Edna; his grandfather, John; and his great-grandfather, Johannes.

He arrived in Chapel Hill from the University of Iowa in 1951. There were twelve other faculty members in the segregated state at the time who he later explained “could best be described as idealistic, imaginative, assertive in their quest for new knowledge, having insatiable curiosity and a healthy skepticism of prior truths and new dogmas.” By 1965, he was Chairman of the Department of Surgery, and he remained in that post for the next 20 years. He stepped down as Chairman at his peak, but continued to operate and teach. By the end of it, he had charted more than 60 years of service to this one singular institution.

But my sustaining image of Tim is not in an operating theater, but at a simple front table, in long white coat emblazoned with his name, simple bow tie against white shirt, in a crowded, humble classroom, jammed with surgical residents of all sizes, shapes, colors, and disciplines, at 1:30 PM every afternoon, Monday through Friday, for the half decade we shared. This was the Pre-operative Conference, his conference.

As later described, “..resident staff presented their patients to be operated upon the following day. All specialties were involved in these presentations and discussions. The resident responsible for the proposed operation would present the patient to the assembled group of faculty and surgical house staff. Pertinent X-rays, laboratory data, and histopathological slides were used to support the diagnosis and proposed management. No problem was considered trivial, and especially all patients merited at least some discussion. Interrogation of the resident would vary and included the basis for the diagnosis, justification for the operative procedure, history of the disease and treatment, the operative approach, and physiological and pathophysiological characteristics of the disease. There was no deference to authority. Traditional concepts of treatment were never justification for the resolution of a particular problem. Each required individual analysis. With all disciplines being represented, there was excellent opportunity for cross-fertilization of ideas.”

When you would present your case, Tim, and other attendings who modeled themselves after Tim, could always be counted on to pepper you with questions – as often about medical history or embryology, as surgical approach. I attended close to 1000 of these collegial interrogations during my training, and from them learned as much or more about humanity as I did surgery.

As Tim would later say, “The individual that is regarded as a very good surgeon, he’s not in that category simply because he operates more rapidly or ties a knot more rapidly. It’s the decisions that he make as he goes along and the ability to recognize the goals of the operation and what’s important and what is unimportant in trying to achieve these goals.”

What was clear to us, and so well illustrated in this sparklingly decent and wonderful man, was that what made you a good surgeon was the same as what made you a good human being. Chapel Hill produced more than one Dean Smith. He was our’s.

For Health Commentary, I’m Mike Magee.

Tags: Colin Thomas MD > Dean Smith > Tim Thomas > UNC > University of North Carolina

Free Immunization Pt. Ed. Video

Posted on | February 5, 2015 | Comments Off on Free Immunization Pt. Ed. Video

Free 8 Minute Patient Ed Video

Free 8 Minute Patient Ed Video

The Religion of Medicine.

Posted on | February 4, 2015 | 6 Comments

Mike Magee

This week, New York Times introspective columnist, David Brooks wrote, “Over the past few years, there has been a sharp rise in the number of people who are atheist, agnostic or without religious affiliation. A fifth of all adults and a third of the youngest adults fit into this category….As secularism becomes more prominent and self-confident, its spokesmen have more insistently argued that secularism should not be seen as an absence — as a lack of faith — but rather as a positive moral creed.”

That got me thinking – and my conclusion was that, for me, and perhaps for my father as well, Medicine has been our religion. This begins to explain my world view and some of the discomfort I feel (and often express) when my fellow disciples fall short on our vows.

Were there a “Ten Commandments” for this religion called “Medicine”, what would they be?

I. Put your patients interests above all other interests, including your own.

II. Believe in science, and make judgements based on the best current knowledge available.

III. If there is a person in need, respond, without prejudice or delay.

IV. Maintain your own physical, mental and spiritual health so that you are able to offer your patients the entire value of your full human potential.

V. Touch your patients – with your hands, with compassion, and with understanding.

VI. Treat each patient as an individual. Maintain faith in the wisdom of individualized decision making within the patient-physician relationship.

VII. Listen carefully to what is said and especially what is unsaid.

VIII. When you make an error, as you surely will, admit it directly, apologize, and learn from it.

IX. Recognize your own prejudices, and work to ensure they do not compromise your ability to care for others.

X. In your actions, behaviors, and beliefs, bring honor to your profession and to all those whose lives have been entrusted to you.

Quietly, without realizing it, I and many other physicians, have been practicing this “religion” for many years. It has brought meaning and value to our lives, and occasions of sorrow and disappointment. For most of our years, we have practiced this religion in the privacy of the patient-physician relationship, applying it’s tenets as best we could, with the encouragement of our fellow disciples, our patients, and their families.

What to do when a disciple transgresses? This always has been a challenge, especially in the early years. Like the time in Raleigh, NC, when on-call, I phoned the attending to let him know an accident victim with a crushed bladder needed to go to the operating room, and his three word response, “Black or White?” That was disappointing.

But in modern times, the boundaries of our religion have extended into the public space, and some of our own disciples have embraced those spaces – in politics, or business, or media – while maintaining a dual identity as “physician”. It is in this public space that I have often experienced discomfort and questioning about my own religion.

Shouldn’t the “church leaders” have been more vocal in admonishing the “legitimate rape” remarks of Congressman Todd Atkins in 2012?

And what about Dr. Rand Paul’s comment on immunizations in the middle of a U.S. Measles epidemic, ““I’ve heard of many tragic cases of walking, talking normal children who wound up with profound mental disorders after vaccines.” Should church leaders go after this wayward public leader/parishioner? He has had no reticience in going after them, like when he said, “The A.M.A. has been struggling for years, and they do not represent doctors across the country. And AAPS has been growing dramatically as doctors who want to fight against big government join together under a different banner. The A.M.A. doesn’t represent me. I’ve never been a member.”

It’s not that this disciple doesn’t have the right to advance the religion of Libertarianism above his own former religion Medicine. Of course he does. But must I still accept him as a member of my religious community since he clearly has made his choice?

Same holds true for Dr. Mehmet Oz. He’s joined the highly profitable religion, “Herbalism”. That’s fine. But does he belong in my church? And why did I have to be led by a third year medical student from Rochester in October, 2014, who had the courage to speak up. Why weren’t my own church leaders challenging this huckster? It’s just a bit unnerving to hear a junior parishioner say aloud what others are thinking, “Organized medicine has an interest in protecting physicians as a profession. They want to maintain the prestige, trust, and income that physicians have historically received in the US. In order to protect the profession as a whole, organized medicine sometimes has to protect individual doctors, even if they are not acting in the best interest of patients. The AMA may fear that undermining Dr. Oz could undermine overall trust in doctors.”

I’m an older parishioner now. I’ve been around this church for a long, long time. And these dual parishioner problems are not new. They’ve tripped up others in the past, like Senator Bill Frist who affirmed, based on video tape reviews, that Terri Schiavo was “not somebody in persistent vegetative state”.

But sometimes, the dual parishioner does us proud, and boldly declares our religion’s supremacy above all others. Take for example, Chick Koop, when on release of his landmark HIV/AIDS Report, said simply, “I’m the nation’s doctor, not the nation’s chaplain.” He’s why I still belong to this religion.

For Health Commentary, I’m Mike Magee

Tags: ama > bill frist > dr > immunization > legitimate rape > measles epidemic > oz > rand paul > terri schiavo > todd atkins

Planning for Evil vs. Planning for Goodness: Why Medicine Should Embrace the Social Sciences.

Posted on | January 30, 2015 | 1 Comment

Mike Magee

An article by Daniel Jonah Goldhagen in last week’s New York Times Sunday Review, “How Auschwitz Is Misunderstood”, created a dramatic contrast to an address I delivered a few days earlier at a New York liberal arts college titled “Closing The Empathy Gap: Leveraging Healthcare Relationships”.

Goldhagan’s major point was that the widely held belief that German “death factories” were created for bureaucratic efficiency was inaccurate. Rather, he explains, it would have been far more “efficient” to murder their victims on site. Why then Auschwitz? In his fifth paragraph he answers the question. “The Nazi leadership created death factories not for expeditious reasons, but to distance the killers from their victims.”

The remaining eight paragraphs tie this historic horror to a distinctly non-empathic world view. As the article states, “It expressed the Nazis’ unparalleled vision that denied a common humanity everywhere, and global intent to eliminate or subjugate all nonmembers of the ‘master race.'” Putting a personal face on the German policy, he notes that “Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS and the man most responsible for putting the Germans’ plans in action, proudly announced in an address in 1943: ‘Whether nations live in prosperity or starve to death interests me only insofar as we need them as slaves for our culture.’”

If creating a non-empathetic world requires planning and distance, then it follows that creating an empathetic world requires planning and intimacy marked by compassion, understanding and partnership.

This is the case I made a few weeks ago relying on work I presented in 2002 to the World Medical Association in Helsinki when serving as the WMA Resident Scholar. The study had shown that in six countries surveyed (U.S., U.K., German, South Africa, Japan and Canada), the most valued relationship in society, second only to family relationships, was the relationship with a physician.

In exploring why that was so consistently the case, simultaneous surveying of thousands of physicians and patients in those countries once again showed consensus in their definition of this relationship. Over 90% of doctors and patients agreed that its’ power derived from its ability to deliver compassion, understanding and partnership.

The study further revealed that, in 2000, the relationship, again consistently in all six countries, was evolving. It was moving from individual to team approaches, from paternalism to partnership, and from individual to mutual decision making.

As for the commonly held desire to evolve from an interventional to a preventive health delivery model, the study demonstrates that health information, flowing directly from the relationship, was far more likely to be followed and deliver desired behavioral change than information from all other sources including the Internet.

Was there room for improvement in this relationship. Yes, certainly. In a series of “gap analyses”, the study uncovered significantly different views when comparing doctors and patients, and reality to the ideal. Where were these gaps?

1. Information seeking: Patients sought out information, independent of their physicians, when faced with illness, far more frequently then their physicians realized. For example,in the U.S., 69% percent of patients said they had sought information independently, while only 35% of physicians believed that their patients had pursued information not provided by them. These gaps were even wider in other countries (Germany: 71%/11%; U.K.: 51%/15%; South Africa: 56%,9%; Japan: 35%/6%)

2. Empathetic Physician Behavior: On five measures of ideal behavior (compassion, trust, understanding, patience, listening), patients in all six countries saw average double digit room for improvement when comparing “ideal” to “reality”. Gaps: US – 19%, UK – 27%, Canada – 17%, Germany – 20%, SA – 12%, Japan – 31%.

3. Access to Physicians: On five measures of ideal access to physicians (attentiveness, time spent, ease of appointment, treatment choice, access to specialists), patients in all six countries saw double digit room for improvement when comparing “ideal” to “reality”. Gaps: US – 25%, UK – 40%, Canada – 29%, Germany – 22%, SA – 14%, Japan – 24%.

Finally, this social science, Harris Poll designed survey revealed that the positive impact of the patient-physician relationship in all countries studied was multifactorial. In addition to reactive care, the relationship contributed to preventive health planning, management of individual and societal fear levels, expansion of individual and societal confidence and optimism, reinforcement of family and community bonds, and maximizing productivity.

The final summary slide two weeks ago, at St. Thomas Aquinas College, said “Civil societies marked by empathy, compassion, and justice, are the result of stable, committed, trusting relationships by members of these societies. Family, educational, and health care relations are critical foundation blocks for any society committed to expanding human potential.”

As the Goldhagen article correctly suggests, preventing a “common humanity” takes work. But certainly then the reverse is true as well – creating a common humanity takes work as well. In retrospect, this study, utilizing social science tools, correctly forecasted the dynamic factors that would help shape the American health delivery system in the decade ahead. And yet it was rejected for publication by the New England Journal of Medicine, though one reviewer of three described it as “provocative”.

The challenge of creating a civil society must advantage existing relationships in a deliberate way. It is a “vision battle” as Eli Ginsberg suggested way back in 1937: “Social life implies control, control implies power, power implies conflict. The more dynamic a society, the more probable the conflict, for the great conservative institutions – the law, the church, the school – operate most efficiently in a static environment. But the phenomenal vitality of modern technology leads ‘to ever new conquests. The economic system is caught up in the advance… the political system follows in the rear… with strange twistings and tergiversations.’ Impotent is thought when in direct conflict with gold and the sword.”

More than ever, health has become a human endeavor with the potential to shape a society for the better. But to do so, medicine, and its educational institutions, must look beyond genomics and the wonders of biotechnology, to consider as well how the social sciences might advance human behavior.

As Eli noted, shortly before Himmler and Hitler broke out of their box, “Economic depression, political revolution, the transvaluations of legal systems, mass psychoses – these, the increasingly typical phenomena of Western civilization – underline the failure of the social sciences to control behavior…The test of genius is not so much the discovery of new facts, as the discovery of new relations between old facts.”

For Health Commentary, I’m Mike Magee

Tags: Auschwitz > Daniel Jonah Goldhagen > Eli Ginzberg > NYT > patient-physician relationship > social science research > wma > world medical association