JAMA Good News Department

Posted on | October 27, 2015 | Comments Off on JAMA Good News Department

JAMA Health Statistics 1969 vs. 2013 (death rates per 100,000)

On the positive side….

Death Rate Overall ⬇ 42.9%

Death from Stroke ⬇ 77.0%

Death from Heart Disease ⬇ 67.5%

Death from Cancer ⬇ 17.9%

Death from Diabetes ⬇ 16.5%

On the negative side….

Death from COPD ⬆ 100% (21 to 42/100,000)

“Wet-Bulb Temperature” – The Limits of Human Endurance and Chaos Ahead

Posted on | October 27, 2015 | 3 Comments

Springfield Republican, Sept. 23, 1988

Mike Magee

On September 23, 1988, I had my first experience with the pressures of a full blown press conference. I was the chief administrative physician at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Massachusetts. Our governor, Michael Dukakis, was running for President of the United States, at the same time (as it turns out) that his State Police Academy was running wild.

The cause for the press conference that Friday afternoon was a deadly combination of heat, overexercise, and physical abuse sanctioned and orchestrated by those in charge of the Massachusetts State Police Academy in Agawam, MA, on September 17, 1988. Our assessment a week later of the 51 victims, one of whom would eventually die of massive liver and kidney failure, was that this was the result of a lethal combination of heat, overexercise and dehydration. My public report on camera that afternoon was met with a stern reproach by leaders of our Health System, some politicians, and members of the Dukakis administration. A cover-up by the State Police, who originally suggested the possibility of contaminated water as the cause, was soon revealed. A month later, a full recounting in People magazine confirmed our initial diagnosis, and added as well documentation of extreme physical and verbal abuse that day.

In any case, from that day forward, I’ve been especially conscious of the danger of heat to humans. And so, yesterday, I read with interest on Discovery.com the dramatic headline, “Burning Hell Coming For Mideast Deserts”. The article, based on a recent report in the journal, Nature Climate Change, first exposed me to the term, “wet bulb temperature”. And then today, the New York Times followed up with an article focused on the term called “The Deadly Combination of Heat and Humidity”.

As it turns out, the proper term is “wet-bulb globe temperature” and it was first used in the 1950’s by the U.S. military. The Army and the Marines were attempting to limit the degree of trainee casualty due to heat stress. They had noted that heat measures alone were not an adequate predictor of problems. They sought a measure that would consider humidity as well. So they wrapped a thermometer in a wet cloth, and then took a measure. They then conducted epidemiologic studies and pegged the critical point where injuries began to appear. But, for some reason, wet-bulb temperature measurements and findings never quite made it onto our athletic fields or public health departments.

According to one emergency physician at George Washington Univesity School of Medicine, beyond a certain point, “your body doesn’t cool anymore” (from sweating). So what is that point? Well that depends on what you’re doing. If you are exercising, your body loses the ability to cool itself through sweat evaporation at a wet-bulb temperature of 80. That same person sitting quitely in the shade will first experience problems at a wet-bulb temperature of 92, and if he sadly falls asleep there, under the tree, at a wet-bulb temperature of 95, he’ll die in six hours. In the Nature Climate Change study, the authors demonstrated that the recent 1.5 degrees of global warming had already resulted in a quadrupling of the likelihood of experiencing exposure to deadly wet-bulb temperatures.

The number of days in danger per year has been averaging four, but if current global warming treads persist, we will experience on average 10 such days per year by 2030. That will seem mild compared to the 17 days in 2050, and even more so compared to the 35 days in 2090. To put some human terms to all this, consider the death rates with heat spells in our recent history: July, 1995 (Chicago) – 700 deaths; August, 2003 (Europe) – 45,000; July, 2010 (Russia) – 54,000. Not small numbers.

India hit a regular temperative of 118 degrees last week with 2500 casualties, which likely triggered the “Burning Hell Coming for Mideast Deserts” article. As one of the Nature Climate Change authors said, “People who have resources will live indoors.” Of course, generating the electricity for air conditioning carries with it a carbon footprint which could make global warming worse. And if you’re poor, you’re out of luck, and on the move to anyplace that’s cooler. Speaking of migration, cultural and historical events like the annual outdoor Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, could become untenable. The same may be true of oil exploration as equipment breaks down and mechanics can’t function in the extreme heat. If you believe the Middle East is unstable now, don’t expect relief any time soon.

The wet-bulb temperature sets the limits of human tolerance. And clearly human behavior is magnifying our population risks. If we begin to act rationally and adopt policies that lower carbon emissions, we will create for ourselves a range of options and greater freedom. If we persist as we have, expect change similar to what the Massachusetts police cadets experienced in 1988. And as a doctor with first hand exposure to that event, let me tell you, it was not a pretty picture.

Tags: carbon footprint > climate change > environmental health > massachusetts state police > michael dukakis > wet-bulb temperature

Sustainable Prevention: At The Intersection of America’s Two Most Powerful Social Networks

Posted on | October 21, 2015 | 2 Comments

Mike Magee

Last week, I made a quick trip to Washington – one day, back and forth, from Hartford, CT. I was there to seek advice from an old friend as we complete planning for the second decade of the Rocking Chair Project. This early childhood intervention program targets young, economically disadvantaged, expectant mothers, supporting them with a physician-led home visit which includes the gift of a upholstered glider rocking chair and ottoman as a “gift of nurturing” for both mother and child. The visits, repeated over 1000 times in the past 10 years, include reinforcement of health messages and an emphasis on long term continuity with the health care system.

The challenge now is scaling up what we know to be a low-cost, highly impactful intervention. We have been relying on individual 2nd year Family Medicine residents around the country to identify the target moms, and to follow through with these “high-touch” visits. It has worked, but requires a fair amount of hands-on coordination and is not easily scalable.

Our lead adviser, Yale Professor Emeritus, Ed Zigler (Father of Head Start), told us a long time ago that the intervention was so low cost and powerful, tapping into two critical social networks (Medicine and Family), that it should be offered to entire populations, not just a lucky few individual patients.

My DC friend summed up the challenge immediately. He said we were seeking “a vertically integrated network with existing distribution channels”. Translation, a well organized, efficient, and financially sustainable system that has the ability to identify the target population prenatally, and already is accustomed to making home visits in the immediate postnatal period.

That doesn’t sound like such a tall order, except for the fact that our health care system, with few exceptions, remains fundamentally fragmented, and our emphasis on treatment over prevention, insures that caregivers usually arrive late to the game. We, and others, have recognized this. The Rocking Chair Project, and many other valiant efforts, have been layered onto the existing system, in the hope of patching up the most obvious system weaknesses. But now, the nagging advice of broad thinkers like Ed Zigler demands fundamental change – this should be available to the entire population, not simply the lucky few.

One group that is attempting to address this challenge in a systematic and optimistic way is the ReThink Health, which is supported by the Fannie E. Rippel Foundation. It was launched in 2007 with the help of luminaries from health, economics, politics, and business including Don Berwick, Elliott Fisher, Marshall Ganz, Laura Landry, Amory Lovins, Jay Ogilvy, Elinor Ostrom, Peter Senge, John Sterman, and David Surrenda.

ReThink Health’s approach is to “awaken changemakers to what is possible.”

How do they do this? In their words, “We spur big-picture thinking that allows leaders to step outside their own frames of reference. This lets them better see how the various parts of the system interact in unexpected ways and determine how and where they can exert influence. We do this by deeply understanding their challenges, listening to diverse voices, and working together to harness the information, insights, and actions needed to overcome entrenched beliefs and disrupt the status quo.”

Certainly “Active Stewardship” and “Sound Strategy” are critical foundation supports, but a third leg they mention is essential as well – “Sustainable Investment and Financing”. One of their regional sites, The Upper Connecticut River Valley (UCRV) ReThink Health, under Executive Director Steve Voight, encompasses two counties in New Hampshire and two counties in Vermont, and includes the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Dartmouth College’s Tuck School of Business, and The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, among their partners. In defining the challenge ahead, they said, “We aspire to create a model that will serve both our region and our country. The path forward is both clear and uncertain. To succeed we will have to be supportive and critical, optimistic and skeptical, cautious and bold. Above all, we will have to trust that by working together we can find a path forward.”

What suggestions might we add from our experience with the Rocking Chair Project?

1. Address your most vulnerable populations first.

2. Start as early in life as possible – that means prenatally.

3. Integrate the multi-generational family, on their terms, in their home settings.

4. Nurture the synergistic power of two social relationships – family and medical.

5. Understand that long term preventive continuity is seeded in the first days of life by demonstrating and advantaging compassion, understanding and partnership.

That’s the Rocking Chair Project.

Tags: Amory Lovins > David Surrenda > Donald Berwick > Elinor Ostrom > elliott fisher > Jay Ogilvy > John Sterman > Laura Landry > Marshall Ganz > Peter Sentge > ReThink Health > ReThink Health UCRV > Rippel Foundation > Rocking Chair Project > Steve Voight

Between A Rock and A Hard Place: The Planetary Patient

Posted on | October 16, 2015 | 2 Comments

Mike Magee

Thirty six years ago, our then President, Jimmy Carter, spoke directly to the American people about governance and energy independence in a speech titled, “Crisis of Confidence” – a speech derisively labeled “The Malaise Speech” by his then Republican Presidential opponent, Ronald Reagan.

Putting aside the fact that Carter never used the word “malaise” in the speech, it is instructive to look back three and a half decades later, and reflect on how much has changed, and how much remains the same, especially when it comes to the “1%” and our planet’s health relative to energy consumption.

Carter begins by sharing quotes from every day Americans that he has recently collected. They include:

“I feel so far from government. I feel like ordinary people are excluded from political power.”

“Some of us have suffered from recession all our lives.”

“Some people have wasted energy, but others haven’t had anything to waste.”

“The big-shots are not the only ones who are important. Remember, you can’t sell anything on Wall Street unless someone digs it up somewhere else first.”

A few paragraphs later, the President reflects, “In a nation that was proud of hard work, strong families, close-knit communities, and our faith in God, too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption. Human identity is no longer defined by what one does, but by what one owns. But we’ve discovered that owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning. We’ve learned that piling up material goods cannot fill the emptiness of lives which have no confidence or purpose.”

Later he describes a Washington that is tied in knots.

“What you see too often in Washington and elsewhere around the country is a system of government that seems incapable of action. You see a Congress twisted and pulled in every direction by hundreds of well-financed and powerful special interests. You see every extreme position defended to the last vote, almost to the last breath by one unyielding group or another.”

If he was prescient about the politics at home, he was a bit short-sighted in his assessment of the energy crisis. Understandably, he sought to stem the tides of importation of oil from the Middle East. As one voter had told him, “ “Our neck is stretched over the fence and OPEC has a knife.” The Commander-in-Chief said, “Energy will be the immediate test of our ability to unite this nation, and it can also be the standard around which we rally. On the battlefield of energy we can win for our nation a new confidence, and we can seize control again of our common destiny.” As we have seen, that morphed into an aggressive philosophy of “Manifest Destiny” a few short decades later.

As for the immediate response to the crisis, as laid out on July 15, 1979, he recommended, “To give us energy security, I am asking for the most massive peacetime commitment of funds and resources in our nation’s history to develop America’s own alternative sources of fuel — from coal, from oil shale, from plant products for gasohol, from unconventional gas, from the sun.”

It’s amazing how, in such a short blink of human history, how much can change. But here we are, with the health of our “planetary patient” now hanging in the balance. Today, the potentially devastating impact of global warming is well understood and accepted by all, except the most stubbornly ignorant or politically expedient. Yet the crisis remains largely unaddressed.

Coal, most now agree, is irreparably dirty, and oil less clean than Carter’s “unconventional gas”. The oil shale, so celebrated in Canada, piled up to flow down a trans-national pipeline that will never be authorized, has become prohibitively expensive, and bears an enormous carbon footprint, as energy prices continue to head south. The promise of solar (and wind), even with continued technologic advances and improving cost effectiveness, has thus far wilted under the withering criticism of traditional fossil fuel energy investors anxious to jump on innovators at every hiccup in development.

A tumultuous Middle East, absent our subsidies as chief importers of their only real export, oil, remains an infectious threat to the “planetary patient”. Ungovernable, and living on the edge of civilization, their human populations cry out for civility, opportunity and modernity.

Our planet is changing, and yet in many ways, we humans stay the same – slow to adapt, wed to self-interest, long on aggression and short on wisdom.

Case in point: Fracking in Oklahoma for “clean natural gas”. Halfway between Tulsa and Oklahoma city sits a town of 8000 called Cushing Hub. It is also home to one of the largest oil tank storage facilities in the world. Which is fine, were it not also host to one of the largest fracking operations on the globe. That effort has resulted in the injection of tens of millions of barrels of wastewater underground. That lubricated liquid has apparently facilitated the movement of previously stable giant rock mantles, allowing them now to more easily slip over and under each other.

That the underground rock is on the move is clear from the numbers. In 2009, the area experienced 3 quakes measuring magnitude 3 or greater. Five years later, there were 585. Currently the Cushing oil storage hub holds 53 million barrels of crude awaiting transport to refineries in the south. In October, 2014, two quakes over 4.0 erupted just below the facility. Scientists are now predicting a 6.0+ quake as highly likely in the near future. One 5.7 or greater would disrupt the facility and cause a massive and devastating spill. Even the states oil and gas regulatory body, the Oklahoma Corporation Commission, is concerned. But the state legislature isn’t too sympathetic. They cut the Commission’s budget by nearly 50% in response to their vocal concerns.

Speaking for the “planetary patient”, here’s the good and the bad news. We’re no longer energy dependent on the Middle East, but have managed to insert ourselves into that unforgiving environment with destabilizing effect, instigating among others problems a mass migration of our fellow humans of Biblical proportions.

Adding to the incredible, war-induced, loss of human life (including many civilians) and massive environmental degradation, we have directed our best energy technology solutions toward a energy choice that is fraught with environmental hazard.

Yes, we have begun to move from dirty to less dirty fossil fuels, and along with China, have begun to address global warming. But we have no rational national environmental controls on fracking. Rather we rely on energy industry controlled state bodies. Often those are the very same bodies who currently have Donald Trump in the lead among Republican primary candidates, and the same bodies responsible for gerrymandering voting districts and designing various new barriers to disenfranchise voting rights for young and poor citizens.

If the “planetary patient” could talk, what would she say about our choices on energy since Carter? Likely, she would note that our United States remains dramatically ununited in the pursuit of truly clean energy. Second, she might remind us that earthquake fault lines do not respect human designated geographic state boundaries. And third, that 35 years after President Carter’s speech, our problem with “crisis in confidence” remains, and will not be cured by high walls or rampant creed or blocking the vote. Rather it will require wise leaders and the will of a majority of determined and enlightened American citizens.

For Health Commentary, I’m Mike Magee

Tags: crisi in confidence > energy policy > fracking > jimmy carter > planetary patient > the malaise speech > tracking

In Support of Patrick Kennedy – and Family Health.

Posted on | October 8, 2015 | 2 Comments

Mike Magee

This week, on October 6th, I hung on to “Morning Joe” a bit longer than I normally do to hear the interview of Patrick Kennedy by Joe Scarborough. My interest was personal, knowing some of the players, but also as a member of a large Catholic family (12 kids) with our own credo of family loyalty and our own share of trials and tribulations.

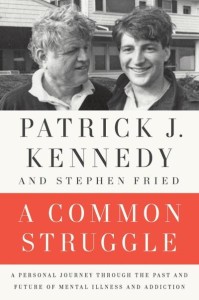

Two days earlier, Lesley Stahl had interviewed him on “60 Minutes”, his first public interview promoting his new memoir, “A Common Struggle”. That interview had veered off subject to Patrick’s father – Was he an alcoholic? Did he suffer from PTSD in the wake of his brothers’ assassinations? Valid questions I suppose, but coming close to suggesting this as just another book about America’s most famous (and tragic) family.

But in reality, Patrick’s book is much more than that. In it, he displays a modern understanding of the meaning of health as “human potential”. He clearly explains that unhealthy behaviors are often inherited, as both genetic and social constructs. And most importantly, he reveals that families, in their conspiracy of silence, often contribute to the problem rather than to the solution – and that communities and leaders are complicit.

In thirteen minutes, last Tuesday, Patrick Kennedy provided more health education on the subject of alcohol addiction, mental health, and their treatment, than I received in nearly a decade of training to be a physician.

As the interview opened, Joe Scarborough alluded to the fact that Patrick had broken some silent code, and at least some family members had reacted angrily. Why did he write the story?

Patrick’s answer, a simple three word sentence, declared his emancipation, and his right to both health and happiness, for he and his wife and children. He said simply: “It’s my story.” But what came through was, “It’s my life, and I’m taking control of it.”

He explained, “Often times you’re expected to keep your parents secrets. And yet it will bedevil you your whole life because we all grow up to be our parents. And everything that happens to you as children, we will live with that for the rest of our lives. And what makes that worse is keeping that secret or thinking that you’re keeping that secret…What I’m saying is that my story about keeping quiet in my family is like every other family in America who has these illnesses. Say nothing! Do nothing! See nothing!”

Patrick goes on to explain that the book explains in detail the policy issues involved with achieving expanded coverage and care for those suffering from mental illness and and addiction. He explains how he and his father wrote the Parity Law. Back then, law makers wanted nothing to do with it. As Patrick said, “No one wanted to be the author of Parity. No one wanted the words mental health and addiction next to their name.” When it did pass, he says, insurance companies wasted little time in figuring out how to renege on their obligations.

It is an individual disease marked by shame. In his words, “One of the biggest barriers is no one wants to be known as a patient who is getting mental health treatment or addiction treatment.” But that shame, for him, was uniquely reinforced by a secret code of silence. This extended not only to his parents, siblings and extended family, but also to the many important visitors and guests who wandered the hallways of his famous home in his formative years. Routinely, he was forced to witness his inebriated and incapacitated mother wandering in bathrobe midday past friends and family, heads down, all of whom refused to acknowledge, let alone confront, the disease. That was its’ cruel power over the family, and in part, over him, until recently.

At the core of his family was this secret, eating away at everyone’s health. As Patrick experienced it, “It’s an illness and we are running away from it. My family does not want to be identified with mental illness. That should tell you something about the shame and stigma that still surrounds this issue.”

So where did he find the courage to stand up to it? For whom, and why now? He said, “I have kids now. I don’t want my kids to feel ashamed because they have a genetic predisposition for mental illness and addiction. I want them to get treatment for them. I don’t want them to keep secret the fact that they have an emotional life, a spiritual life. We ought to be paying as much attention to their mental health as the rest of their physical health.”

The reaction from the family has been mixed. His older brother and his mother have issued statements disavowing and criticizing the book. Most family members have remained silent. And a few of the extended family have voiced support. Those who have focused on his right to speak out. In his words, “… a number of members of the family said I love your message that this is about breaking the silence and shame because all of us are saddled with the hangover of a shame that comes with growing up where you are not supposed to tell anything about what happened to you personally. That affects somebody if they are growing up in a family where everything is supposed to be kept quiet.”

As for the disapproval of his older brother, he said simply, “I love him, and I will always love him.” And added, “All I can do is do the next right thing and pray that my brother will understand that what I’m trying to do here is bigger than both of us. And that’s what my dad was all about – trying to make a difference for more people. I’m trying to move the ball forward as he did in his life.”

For Health Commentary, I’m Mike Magee

Tags: A Common Struggle > addiction > alcoholism > Family Health > Mental Health Partity > Mental illness > Patrick Kennedy > Ted Kennedy

The 2015 VA Assessment Report – Whose Interests Would It Serve?

Posted on | October 1, 2015 | 2 Comments

Mike Magee

To say the VA is a huge enterprise is a bit of an understatement. Over 9 million patients in a system with nearly 300,000 employees (including 20,000 doctors) and an annual budget just under $60 billion.

If the system is big, it is also controversial, and has been for a long, long time. There have been no less than 137 formal assessments of the system in the past. Falsification of waiting lists was what triggered the latest crisis. But issues of highly variable quality of care, delayed access, a phenomenal mental health disease burden, an historic and troubled step-sister relationship with academic medical centers, and decaying brick and mortar have been visible for decades.

In signing the Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act of 2014, President Obama provided a safety valve in allowing a non-VA treatment option for the unmet medical needs of veterans, but also funded an comprehensive assessment of VA performance in a dozen areas of delivery and management.

On September 18, 2015, the results became public, and sounded dire. To begin with, the capital needs of the system are pegged at $51 billion over the next decade. By the way, cost of construction inside the system is double that of the private sector. Timely access to a health professional requires more of everything, says the report – more staff, more exam rooms, more decision control close to the patient. The only thing that we require less of, apparently, is competing internal management silos.

There are a lot of “funny numbers” when it comes to the VA. For example, there are nearly 22 million living veterans in the U.S. But only 4 in 10 are actually enrolled in the VA health care system. Of those 9 million enrollees, only about 6 million are actual patients, and of these, on average, each receives less than 50% of his/her care from the VA. So effectively, and functionally, the system is actually servicing the full time equivalent of 3 million patients at a cost of $60 billion dollars. (And that doesn’t include the additional infusion of “research dollars” and special grants that find their way into the system). That is $20,000 + per year for each “full time equivalent” patient cared for in a system which, in the just released assessment “scored in the bottom quartile on every measure of organizational health”.

With all that, one would think that the solution to this problem could be delivered in just 5 words: “Time to close the doors”. But no, the solutions, as expressed by leaders of the assessment committee in this week’s New England Journal of Medicine, are far less definitive.

It reads, “The solution, we believe, is multidimensional but starts with immediate changes in practice that will ultimately change culture. It requires pushing decision rights, authority, and responsibilities down to the lowest appropriate administrative level and increasing the appeal of senior leadership positions by pursuing regulatory or legislative changes that create new classifications for VHA leaders. It’s important for VHA leadership to foster a ubiquitous patient-centric culture that encourages sharing of best practices (and failures), values feedback, and catalyzes innovation. To enhance continuity, we believe Congress should consider longer terms for key VHA leaders and medical center directors.”

A bit later, “We call for a shift in VHA focus from central bureaucracy to supporting clinicians in the field and clearly articulating what decision authority resides at each level of the organization. Most important, a systematic approach is needed for identifying and disseminating best practices.”

And finally, “Although VHA transformation will be a Herculean challenge, the country’s current shared sense of urgency and uniform commitment to veterans requires settling for nothing less than high-quality care at sustainable cost and within a culture comparable to that of the best health care organizations.”

A 2014 assessment of clinical preparedness in the AAMC journal, Academic Medicine, said this, “Since 2001, about 2.5 million U.S. troops have been deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan. More than 6,600 men and women have given their lives, and over 48,000 have been injured. However, these numbers do not reflect the long-term physical, psychological, social, and economic effects of deployment on service members and their families. With over one million service members separating from the military over the next several years, it seems prudent to ask whether our country’s health care professionals and systems of care are prepared to evaluate and treat the obvious and more subtle injuries ascribed to military deployment and combat.”

It also said this, “In fact, by itself, it cannot even ensure the health of the 40% of veterans enrolled in VA health care. Some three-quarters of those enrolled in VA health care also have alternate sources of health coverage, such as Medicare, Medicaid, or private insurance, and many of these veterans receive at least some portion of their health care outside the VA system. Ensuring veterans’ well-being is a duty for the entire health professions community.”

Since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, veterans have access to new insurance options that allow them to more easily opt-out of the broken VA system. And they are doing just that, in increasing numbers. So why does the most recent evaluation so clearly unlink reality (It is questionable whether the system is worth saving), with solution (Close it down, and merge these patients into our existing health delivery system)?

Part of the answer is likely geography and jobs. As with the “military-industrial complex” and military bases, these entities are spread throughout our nation, and closing them would have an immediate impact on jobs and local economies. These geographies have political representatives, and the institutions and their suppliers, who profit through weak controls, have their own networks and lobbyists who battle on, in their behalf.

But it is useful to also remember that these entities are an integral part of a larger “medical-industrial complex” which is not as readily visible, and includes the leaders of our academic health care institutions and corporate health care firms. These leaders were, in the post- WWII period, chosen to provide significant thought leadership and human resource supplies for the entire system. Today, 80% of U.S. medical schools have an active affiliation with a VA hospital. The academic medical centers and medical schools rotate over 100,000 residents and medical students through the VA, and receive a not insignificant portion of their training at these sites. Researchers from the academic centers also gain access to research subjects at the VA, and are funded by corporate and governmental grants for their studies.

The question worth asking then is who and what are the latest set of recommendations ultimately designed to serve – the veterans or the “military-industrial complex” whose interests continue to be served, even by an irreconcilably flawed system?

For Health Commentary, I’m Mike Magee.

Tags: 2015 VA Report > VA > Veterans access choice and accountability act of 2014 > Veterans Administration

Pope to Congress: The Art of Politics, and The Promotion of Health.

Posted on | September 24, 2015 | Comments Off on Pope to Congress: The Art of Politics, and The Promotion of Health.

Mike Magee

If health is about human potential, and if what we in the caring professions are challenged to do is “to heal, provide health, and keep families and communities whole”, then what we do is a holy pursuit.

In his remarks to Congress this morning, Pope Francis said as much. In addition to providing a seminar on the art and purpose of politics in society, the Pope hit on two themes central to Health Commentary over the past decade: 1) Health is Political, 2) It is imperative that we care for “The Planetary Patient”.

All health professionals would benefit from a careful reading of Pope Francis’s remarks which follow:

_______________________________________________________________________________

“I am most grateful for your invitation to address this Joint Session of Congress in “the land of the free and the home of the brave”. I would like to think that the reason for this is that I too am a son of this great continent, from which we have all received so much and toward which we share a common responsibility.

Each son or daughter of a given country has a mission, a personal and social responsibility. Your own responsibility as members of Congress is to enable this country, by your legislative activity, to grow as a nation. You are the face of its people, their representatives. You are called to defend and preserve the dignity of your fellow citizens in the tireless and demanding pursuit of the common good, for this is the chief aim of all politics. A political society endures when it seeks, as a vocation, to satisfy common needs by stimulating the growth of all its members, especially those in situations of greater vulnerability or risk. Legislative activity is always based on care for the people. To this you have been invited, called and convened by those who elected you.

Yours is a work which makes me reflect in two ways on the figure of Moses. On the one hand, the patriarch and lawgiver of the people of Israel symbolizes the need of peoples to keep alive their sense of unity by means of just legislation. On the other, the figure of Moses leads us directly to God and thus to the transcendent dignity of the human being. Moses provides us with a good synthesis of your work: you are asked to protect, by means of the law, the image and likeness fashioned by God on every human face.

Today I would like not only to address you, but through you the entire people of the United States. Here, together with their representatives, I would like to take this opportunity to dialogue with the many thousands of men and women who strive each day to do an honest day’s work, to bring home their daily bread, to save money and – one step at a time – to build a better life for their families. These are men and women who are not concerned simply with paying their taxes, but in their own quiet way sustain the life of society. They generate solidarity by their actions, and they create organizations which offer a helping hand to those most in need.

I would also like to enter into dialogue with the many elderly persons who are a storehouse of wisdom forged by experience, and who seek in many ways, especially through volunteer work, to share their stories and their insights. I know that many of them are retired, but still active; they keep working to build up this land. I also want to dialogue with all those young people who are working to realize their great and noble aspirations, who are not led astray by facile proposals, and who face difficult situations, often as a result of immaturity on the part of many adults. I wish to dialogue with all of you, and I would like to do so through the historical memory of your people.

My visit takes place at a time when men and women of good will are marking the anniversaries of several great Americans. The complexities of history and the reality of human weakness notwithstanding, these men and women, for all their many differences and limitations, were able by hard work and self- sacrifice – some at the cost of their lives – to build a better future. They shaped fundamental values which will endure forever in the spirit of the American people. A people with this spirit can live through many crises, tensions and conflicts, while always finding the resources to move forward, and to do so with dignity. These men and women offer us a way of seeing and interpreting reality. In honoring their memory, we are inspired, even amid conflicts, and in the here and now of each day, to draw upon our deepest cultural reserves.

I would like to mention four of these Americans: Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton.

This year marks the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, the guardian of liberty, who labored tirelessly that “this nation, under God, [might] have a new birth of freedom”. Building a future of freedom requires love of the common good and cooperation in a spirit of subsidiarity and solidarity.

All of us are quite aware of, and deeply worried by, the disturbing social and political situation of the world today. Our world is increasingly a place of violent conflict, hatred and brutal atrocities, committed even in the name of God and of religion. We know that no religion is immune from forms of individual delusion or ideological extremism. This means that we must be especially attentive to every type of fundamentalism, whether religious or of any other kind. A delicate balance is required to combat violence perpetrated in the name of a religion, an ideology or an economic system, while also safeguarding religious freedom, intellectual freedom and individual freedoms. But there is another temptation which we must especially guard against: the simplistic reductionism which sees only good or evil; or, if you will, the righteous and sinners. The contemporary world, with its open wounds which affect so many of our brothers and sisters, demands that we confront every form of polarization which would divide it into these two camps. We know that in the attempt to be freed of the enemy without, we can be tempted to feed the enemy within. To imitate the hatred and violence of tyrants and murderers is the best way to take their place. That is something which you, as a people, reject.

Our response must instead be one of hope and healing, of peace and justice. We are asked to summon the courage and the intelligence to resolve today’s many geopolitical and economic crises. Even in the developed world, the effects of unjust structures and actions are all too apparent. Our efforts must aim at restoring hope, righting wrongs, maintaining commitments, and thus promoting the well-being of individuals and of peoples. We must move forward together, as one, in a renewed spirit of fraternity and solidarity, cooperating generously for the common good.

The challenges facing us today call for a renewal of that spirit of cooperation, which has accomplished so much good throughout the history of the United States. The complexity, the gravity and the urgency of these challenges demand that we pool our resources and talents, and resolve to support one another, with respect for our differences and our convictions of conscience.

In this land, the various religious denominations have greatly contributed to building and strengthening society. It is important that today, as in the past, the voice of faith continue to be heard, for it is a voice of fraternity and love, which tries to bring out the best in each person and in each society. Such cooperation is a powerful resource in the battle to eliminate new global forms of slavery, born of grave injustices which can be overcome only through new policies and new forms of social consensus.

Politics is, instead, an expression of our compelling need to live as one, in order to build as one the greatest common good: that of a community which sacrifices particular interests in order to share, in justice and peace, its goods, its interests, its social life. I do not underestimate the difficulty that this involves, but I encourage you in this effort.Here too I think of the march which Martin Luther King led from Selma to Montgomery fifty years ago as part of the campaign to fulfill his “dream” of full civil and political rights for African Americans. That dream continues to inspire us all. I am happy that America continues to be, for many, a land of “dreams”. Dreams which lead to action, to participation, to commitment. Dreams which awaken what is deepest and truest in the life of a people.

In recent centuries, millions of people came to this land to pursue their dream of building a future in freedom. We, the people of this continent, are not fearful of foreigners, because most of us were once foreigners. I say this to you as the son of immigrants, knowing that so many of you are also descended from immigrants. Tragically, the rights of those who were here long before us were not always respected. For those peoples and their nations, from the heart of American democracy, I wish to reaffirm my highest esteem and appreciation. Those first contacts were often turbulent and violent, but it is difficult to judge the past by the criteria of the present. Nonetheless, when the stranger in our midst appeals to us, we must not repeat the sins and the errors of the past. We must resolve now to live as nobly and as justly as possible, as we educate new generations not to turn their back on our “neighbors” and everything around us. Building a nation calls us to recognize that we must constantly relate to others, rejecting a mindset of hostility in order to adopt one of reciprocal subsidiarity, in a constant effort to do our best. I am confident that we can do this.

Our world is facing a refugee crisis of a magnitude not seen since the Second World War. This presents us with great challenges and many hard decisions. On this continent, too, thousands of persons are led to travel north in search of a better life for themselves and for their loved ones, in search of greater opportunities. Is this not what we want for our own children? We must not be taken aback by their numbers, but rather view them as persons, seeing their faces and listening to their stories, trying to respond as best we can to their situation. To respond in a way which is always humane, just and fraternal. We need to avoid a common temptation nowadays: to discard whatever proves troublesome. Let us remember the Golden Rule: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” (Mt 7:12).

This Rule points us in a clear direction. Let us treat others with the same passion and compassion with which we want to be treated. Let us seek for others the same possibilities which we seek for ourselves. Let us help others to grow, as we would like to be helped ourselves. In a word, if we want security, let us give security; if we want life, let us give life; if we want opportunities, let us provide opportunities. The yardstick we use for others will be the yardstick which time will use for us. The Golden Rule also reminds us of our responsibility to protect and defend human life at every stage of its development.

This conviction has led me, from the beginning of my ministry, to advocate at different levels for the global abolition of the death penalty. I am convinced that this way is the best, since every life is sacred, every human person is endowed with an inalienable dignity, and society can only benefit from the rehabilitation of those convicted of crimes. Recently my brother bishops here in the United States renewed their call for the abolition of the death penalty. Not only do I support them, but I also offer encouragement to all those who are convinced that a just and necessary punishment must never exclude the dimension of hope and the goal of rehabilitation.

In these times when social concerns are so important, I cannot fail to mention the Servant of God Dorothy Day, who founded the Catholic Worker Movement. Her social activism, her passion for justice and for the cause of the oppressed, were inspired by the Gospel, her faith, and the example of the saints.

How much progress has been made in this area in so many parts of the world! How much has been done in these first years of the third millennium to raise people out of extreme poverty! I know that you share my conviction that much more still needs to be done, and that in times of crisis and economic hardship a spirit of global solidarity must not be lost. At the same time I would encourage you to keep in mind all those people around us who are trapped in a cycle of poverty. They too need to be given hope. The fight against poverty and hunger must be fought constantly and on many fronts, especially in its causes. I know that many Americans today, as in the past, are working to deal with this problem.

It goes without saying that part of this great effort is the creation and distribution of wealth. The right use of natural resources, the proper application of technology and the harnessing of the spirit of enterprise are essential elements of an economy which seeks to be modern, inclusive and sustainable. “Business is a noble vocation, directed to producing wealth and improving the world. It can be a fruitful source of prosperity for the area in which it operates, especially if it sees the creation of jobs as an essential part of its service to the common good” (Laudato Si’, 129). This common good also includes the earth, a central theme of the encyclical which I recently wrote in order to “enter into dialogue with all people about our common home” . “We need a conversation which includes everyone, since the environmental challenge we are undergoing, and its human roots, concern and affect us all” .

In Laudato Si’, I call for a courageous and responsible effort to “redirect our steps” , and to avert the most serious effects of the environmental deterioration caused by human activity. I am convinced that we can make a difference and I have no doubt that the United States – and this Congress – have an important role to play. Now is the time for courageous actions and strategies, aimed at implementing a “culture of care” and “an integrated approach to combating poverty, restoring dignity to the excluded, and at the same time protecting nature” . “We have the freedom needed to limit and direct technology” ; “to devise intelligent ways of… developing and limiting our power” ; and to put technology “at the service of another type of progress, one which is healthier, more human, more social, more integral” . In this regard, I am confident that America’s outstanding academic and research institutions can make a vital contribution in the years ahead.

A century ago, at the beginning of the Great War, which Pope Benedict XV termed a “pointless slaughter”, another notable American was born: the Cistercian monk Thomas Merton. He remains a source of spiritual inspiration and a guide for many people. In his autobiography he wrote: “I came into the world. Free by nature, in the image of God, I was nevertheless the prisoner of my own violence and my own selfishness, in the image of the world into which I was born. That world was the picture of Hell, full of men like myself, loving God, and yet hating him; born to love him, living instead in fear of hopeless self-contradictory hungers”. Merton was above all a man of prayer, a thinker who challenged the certitudes of his time and opened new horizons for souls and for the Church. He was also a man of dialogue, a promoter of peace between peoples and religions.

From this perspective of dialogue, I would like to recognize the efforts made in recent months to help overcome historic differences linked to painful episodes of the past. It is my duty to build bridges and to help all men and women, in any way possible, to do the same. When countries which have been at odds resume the path of dialogue – a dialogue which may have been interrupted for the most legitimate of reasons – new opportunities open up for all. This has required, and requires, courage and daring, which is not the same as irresponsibility. A good political leader is one who, with the interests of all in mind, seizes the moment in a spirit of openness and pragmatism. A good political leader always opts to initiate processes rather than possessing spaces .

Being at the service of dialogue and peace also means being truly determined to minimize and, in the long term, to end the many armed conflicts throughout our world. Here we have to ask ourselves: Why are deadly weapons being sold to those who plan to inflict untold suffering on individuals and society? Sadly, the answer, as we all know, is simply for money: money that is drenched in blood, often innocent blood. In the face of this shameful and culpable silence, it is our duty to confront the problem and to stop the arms trade.

Three sons and a daughter of this land, four individuals and four dreams: Lincoln, liberty; Martin Luther King, liberty in plurality and non-exclusion; Dorothy Day, social justice and the rights of persons; and Thomas Merton, the capacity for dialogue and openness to God.

Four representatives of the American people.

I will end my visit to your country in Philadelphia, where I will take part in the World Meeting of Families. It is my wish that throughout my visit the family should be a recurrent theme. How essential the family has been to the building of this country! And how worthy it remains of our support and encouragement! Yet I cannot hide my concern for the family, which is threatened, perhaps as never before, from within and without. Fundamental relationships are being called into question, as is the very basis of marriage and the family. I can only reiterate the importance and, above all, the richness and the beauty of family life.

In particular, I would like to call attention to those family members who are the most vulnerable, the young. For many of them, a future filled with countless possibilities beckons, yet so many others seem disoriented and aimless, trapped in a hopeless maze of violence, abuse and despair. Their problems are our problems. We cannot avoid them. We need to face them together, to talk about them and to seek effective solutions rather than getting bogged down in discussions. At the risk of oversimplifying, we might say that we live in a culture which pressures young people not to start a family, because they lack possibilities for the future. Yet this same culture presents others with so many options that they too are dissuaded from starting a family.

A nation can be considered great when it defends liberty as Lincoln did, when it fosters a culture which enables people to “dream” of full rights for all their brothers and sisters, as Martin Luther King sought to do; when it strives for justice and the cause of the oppressed, as Dorothy Day did by her tireless work, the fruit of a faith which becomes dialogue and sows peace in the contemplative style of Thomas Merton.

In these remarks I have sought to present some of the richness of your cultural heritage, of the spirit of the American people. It is my desire that this spirit continue to develop and grow, so that as many young people as possible can inherit and dwell in a land which has inspired so many people to dream.

God bless America!”

Tags: equality > Health is Political > human potential > justice > Pope remarks to Congress > poverty > the planetary patient