How Do We Compare To Ourselves in Health Care?

Posted on | March 3, 2016 | Comments Off on How Do We Compare To Ourselves in Health Care?

David Blumenthal M. D. of the Commonwealth Fund did a little comparison shopping in a JAMA article on Health Care Reform. But instead of simply comparing our system to those in Europe, he compared us to ourselves.

Here’s what he had to say:

“Given some Americans’ skepticism of foreign experience, home-grown examples may be more compelling. The Commonwealth Fund State Scorecard3 suggests that (1) if US health spending per person averaged the same nationally as among the 5 lowest-cost states (Utah, Arizona, Georgia, Idaho, and Nevada), an estimated $535 billion (approximately 20%) less would have been spent on personal health services in 2014; (2) if rates of health insurance coverage averaged the same nationally as among the 5 areas with the highest rates (Massachusetts; Vermont; Hawaii; Washington, DC; and Iowa), an estimated 20 million more Americans would have been insured in 2014; and (3) if the national levels of mortality amenable to health care averaged the same as among the 5 states with the lowest rates (Minnesota, Vermont, New Hampshire, Utah, and Colorado), an estimated 77 000 fewer deaths would have occurred in 2014.

The country is large and diverse, and cross-regional comparisons may overlook limits on what any 1 place can achieve. However, such benchmarking strongly suggests that major gains in US health system performance are possible and could yield huge benefits for the American people.”

Virginia Tech Engineering Students Live Their Professional Ethics

Posted on | February 29, 2016 | 2 Comments

Source: VA Tech student

Mike Magee

Attention all health professional students! I would like to introduce you to 3 friends of mine. Well, to be accurate, they are not really friends, in fact I have never met them in person. Nonetheless, I greatly admire them, and am anxious for you to know their names.

They are William Rhoads, Rebekah Martin, and Siddhartha Roy. You may not know them, but they are at least aware of you. They recently wrote: “Engineers don’t take oaths similar to medical doctors’ Hippocratic Oath, but maybe we should. As a start, we have all made personal and professional pledges that include the first Canon of Civil Engineering: to uphold the health and well-being of the public above all else. In doing so, we affirm Virginia Tech’s motto, ‘Ut prosim,’ which means, ‘That I may serve.’”

The three are engineering doctoral students of Virginia Tech professor, Dr. Marc Edwards. In April, Dr. Edwards was contacted out of the blue by Lee Anne Walters, a Flint, Michigan mother of a lead-poisoned child. By then, Ms. Walters, had been betrayed by the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ), who would subsequently be proven to have “violated federal regulations”. Once obstructed, Ms. Walters sent tap water samples from her home to EPA Region 5 employee, Miguel Del Toral, who then collaborated with Dr. Edwards, and discovered that the tap water contained 2,000 parts per billion of lead, 130 times the allowable level.

When they sent the findings back to the MDEQ, they encountered a wholesale cover-up, and no corrective action. By then, the MDEQ was fully aware of the cause of the environmental disaster – a cost-saving 2014 action which switched the city from treated Detroit water to untreated Flint River water whose corrosive chemicals were leaching lead from ancient water pipes into the drinking water.

What to do? Edwards and his students discussed it, not just as a scientific challenge, but as an ethical dilemma. In the face of no committed resources, no geographic legitimacy, and active obstruction from the regional governmental body, there was more than enough reason to drop the issue. After all, here they were, on a campus in Virginia, 500 miles southeast of Flint. But that’s not what happened.

Instead, Dr. Edward, encouraged by his students, which now included two dozen volunteers, went “all in”. Edwards halted other funded research, and shifted $150,000 to the effort. Their first step was to mail out 300 sampling kits to Flint volunteers, who subsequently gathered 861 water samples over a single month.(MDEQ had run only 7 tests in the prior 6 months). The sample collection was subjected to very rigorous tracking and management since the students knew the validity of results would be challenged by the MDEQ

Next, The Virginia Tech students made several visits to Flint, meeting with residents, involving them in advocacy planning, and establishing trust which had long since disappeared. When requests for records went unanswered, the students demanded the files under the Freedom of Information Act, and uncovered proof that the MDEQ had misinformed the EPA that there was a corrosive control program in place, and had illegally discarded customer samples. Finally, the group teamed up with Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha at Hurley Medical Center and collected and released results of the blood lead levels of Flint children.

These final actions tripped a state of emergency, a switch back to Detroit water and direct involvement of the Obama Administration. MDEQ received a blistering review by Virginia Tech professor, Yanna Lambrinidou, who wrote that they were “understaffed, underfunded, lack knowledge and experience.” The students could have easily left it there, a isolated case of the bad guys brought to justice. But they and their Research professor sponsor knew instinctively that this was not the case. Rather, they examined the structural deficits that allowed this to happen:

- 150,000 different public water utilities in the U.S., with highly variable standards of excellence in examining the nation’s water for more than 80 contaminants.

- High degrees of unreliable reporting up though the vertical system of control – from local, to regional EPA, to national EPA.

- Highly variable levels of skill and engineering expertise within local water management offices.

- An EPA that is under-resourced in personnel and funding.

As impressive are the professional insights William, and Rebekah and Siddhartha have drawn from their unique educational mission.

“We are worried that a reward structure has developed that supports mainly self-promotion and dissuades the altruistic motives to do science for the public good that attracted many of us to the profession in the first place.”

“Our experience in Flint has shown us some unpleasant costs of doing good science. It can mean burning bridges to potential funding, and damage to your name and professional reputation. There also are emotional costs associated with distinguishing right from wrong in moral and ethical gray areas, and personal costs when you begin to question yourself, your motives and your ability to make a difference.”

Each and every health professional student could do well to emulate these three, and their fellow students, who went “all in” in serving the “first Canon of Civil Engineering: to uphold the health and well-being of the public above all else.” And for your teachers, many of whom have become entangled in the “Medical-Industrial Complex”, would each of them stand tall if faced with a similar call to action?

Tags: CDC > engineering canon > flint > flint water crisis > medical ethics > virginia tech

AMA’s New Sunbeam Crisis: The AMA Federation’s “Trojan Horse”

Posted on | February 25, 2016 | 3 Comments

Source:Wikipedia

Mike Magee

In August, 1997, the leadership of the AMA ignited an existential crisis by agreeing to loan their imprimatur to the Sunbeam corporation. The imprimatur, along with an AMA endorsement, was to be assigned to Sunbeam products in nine home-care categories including heating pads, vaporizers and blood pressure cuffs. In return, the Florida based company, led by the notoriously aggressive Al Dunlap, was to provide millions in royalties.

As soon as the deal was announced, all hell broke lose. Consumer advocates, legislators, and AMA members openly criticized the deal. Within a week, there was a highly critical New York Times editorial. That was enough for the AMA Board to intervene, launch an independent internal investigation, fire their executive vice president and four other staffers, and ultimately settle with Sunbeam for breaking the contract at the cost of $10 million dollars.

That is how seriously the AMA took the integrity of their imprimatur. All the more surprising then, that they have allowed pharmaceutical manufacturers to access the power and might of that very same imprimatur through their own organizational back door. The “trojan horse” that has facilitated entry is none other than the AMA Federation’s vaulted specialty societies.

The AMA’s unwillingness or inability to provide strict quality control over its now 121 specialty societies was revealed as a result of the publicity surrounding Nobel Prize economist Angus Deaton’s finding that the survival curve in middle aged, white American males had curved downward over the past decade as a result of prescription opioid abuse, most especially of OxyContin.

OxyContin is produced by Purdue Pharma, a one drug firm begun as Purdue Frederick Co. in 1952 by Academic Medicine’s favorite philanthropist, Arthur M. Sackler, MD. Sackler was the father of modern pharmaceutical marketing, whose feats were well catalogued in the biography accompanying his posthumous induction into the Medical Marketing Hall of Fame in 1997.

Sackler’s game book was remarkably consistent over the years. By following these five steps, he became one of the lead designers of the modern Medical-Industrial Complex.

Step 1. Create a quasi-medical organization for legitimacy.

Step 2. Provide funding to the organization to sponsor quasi-academic vehicles (journals and CME programs) to publish supportive articles, and then re-educate practitioners toward the medicalization of your target condition and the need for treatment of this condition with your therapy.

Step 3. Expand the number of professional and consumer organizations to create momentum, demand, and implied consensus.

Step 4. Integrate these programs with mainstream intelligentsia by ample funding in high end medical journals and generous philanthropic support of brand institutions, so that by simple name association, you reinforce your own brand’s integrity.

Step 5. When over-prescribing ignites a backlash, generously and magnanimously participate in the corrective steps, which you yourself made necessary.

Exactly how and when the Purdue Pharma “trojan horse” penetrated the venerable AMA Federation has been well documented in prior publications. What is abundantly clear is that the area of pain management is clearly over-represented and ethically compromised within the AMA Federation. Beyond the historic societies that cover psychiatry, neurology, anesthesiology, emergency medicine, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and oncology (all of whom have strands devoted to pain management), there are also The American Academy of Pain Medicine (1983), The American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (1988), the American Society of Addiction Medicine (1988), and The American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (1998).

The prior series, the Man-made Opioid Epidemic, documented the fundamental absence of any meaningful quality control checks on the AMA’s own Federation members. In a recent AMA blog post, AMA Presidency Steven J. Stack, M.D., writes, “We have a defining moment before us—the kind of moment that we will look back on in years to come as one in which we as a profession rose to the challenge to save our patients, our families and our communities during a time of crisis.”

He then encourages physician members to cooperate with prescription drug monitoring programs and improve their education of how best to approach opioid prescribing. Where should they turn for such education? Stack suggests, “The AMA has gathered more than 100 state and specialty-specific education resources in a one-stop shop for the best and most up-to-date education that organized medicine has to offer. Be sure to take advantage of these materials.”

These include the very same Sackler-infused, Purdue-dominated, OxyContin-fueled characters who ignited this whole mess to begin with. These are the inventors of “pain – the 5th vital sign”, the marketers disguised as CME providers, the malleable state medical board leaders, the patent holders of delayed release technology which they assured rendered OxyContin “addiction proof”.

What then should President Stack and the AMA Board of Trustees do instead? As with the Sunbeam crisis, they should fund an immediate, thorough, internal investigation directed at their own management standards and the ethical integrity of their state and specialty societies. Individuals and associations found to be directly responsible for this modern day Sunbeam crisis should be permanently severed from the organization.

The AMA has a systemic problem that requires immediate attention. If left unaddressed, it poses a much greater risk to the organization than Sunbeam ever did. Questions that the AMA Board of Trustees need to address include:

1. As with 501C3’s, should each national member be required to submit a full financial report, including educational offerings, and complete list of sponsors each year?

2. Should leadership of participating member organizations be required to complete and sign-off on a conflict of interest online program each year to maintain membership?

3. Should Federation member websites be required to include a “sponsor” heading in their navigation bar displaying a complete list of commercial sponsors/advertisers which provided financial/in-kind support for operations, CME funding, public affairs funding, and/or journal advertisements, for the past 5 years, including donations to the member organization and any associated Foundations?

4. Should the results of that annual declaration be available on the AMA public website?

5. Has the AMA ever decertified a Federation National Medical Society? Which, when, and why?

6. Should the AMA establish formal Quality Assessment of their Federation members focused not on membership, but on educational, financial, and ethical performance?

Tags: ama > AMA Board of Trustees > AMA Federation > AMA specialty societies > american medical association > Arthur M. Sackler > medical ethics > oxycontin > purdue pharma > Steven J. Stack

Forward Psychiatry in WW II – The Bias Toward Medicalization and Pharmacologic Intervention.

Posted on | February 12, 2016 | Comments Off on Forward Psychiatry in WW II – The Bias Toward Medicalization and Pharmacologic Intervention.

Mike Magee

My father was one of the 45,000 military doctors to serve in WW II. He entered active duty after his internship in late 1943. By March, 1944, he found himself in Texas receiving special training in Psychiatry. Six months later he would be awarded a Bronze star for his service as an emergency commander of a neuropsychiatric hospital in a war zone in Southern France. Since America’s entry into the war, the Army had attempted to pre-identify and reject any candidates who might be pre-disposed to becoming psychiatric casualties under fire. Military leaders believed selection had been too liberal in WW I, and that this had resulted in high levels of psychiatric distress on the battlefield. By the time my father entered the European war theater, some 2 million draftees or 12% of those examined had been rejected using the military’s new stricter selection criteria. Of the 5 million rejected on medical grounds, nearly 40% were labelled “neuropsychiatric”.

All of this would have been fine with Army Chief of Staff, General George Marshall, if it had worked. But in the first major test, America’s invasion of French North Africa in Tunisia, American psychiatric casualties were occurring at double the rate seen in World War I. A startling 34% of all battle casualties were labelled neuropsychiatric. Based on the military criteria and rules validated by the new Army Chief of Psychiatry William Menninger, a psychiatric label on the battlefield earned you a one way ticket home. Marshall had had enough. He abolished the screening, and re-enlisted a majority of the men that had been rejected on neuropsychiatric grounds. A later study found that 82% of these former rejectees performed successfully as soldiers.

With involvement in selection gone, Menninger and his Psychiatric colleagues concentrated on battlefield management of what had been loosely labelled “shell shock”. Since World War I there had been disagreement whether the constellation of symptoms that had appeared in 15% of the soldiers was a physiologic condition or some kind of psychological problem. The symptoms included everything from stuttering and crying to deafness and blindness, from hallucinations and amnesia to chest pain and inability to breath. Fundamentally, these soldiers were out of commission, at least for a period of time.

The approach settled on in WW I involved intervention as early as possible and as close to the point of injury as could safely be accomplished. This meant putting psychiatric support into the field and positioning it close to the action. Affected soldiers were initially treated with rest, sedation and warm food. This was reinforced with optimism, persuasion and suggestion. The condition the soldiers were told was “normal” and not their fault. They would get better. Military medical leaders then believed this first step could successfully put about 65% of the soldiers back on the front within 4 or 5 days. If not, the soldiers were shipped to facilities some 15 miles from the front and treated “more aggressively”. If that didn’t work, they went to base hospitals 50 miles from the action and spent 3 months in recovery. If that failed, then, and only then, would they be shipped home.

Marshall liked this approach, especially the part about not linking the condition to an automatic and immediate ticket home. The experience in Tunisia had shown that the more inexperienced the Medical Corps team was, the quicker casualties would be labeled “neuropsychiatric” and shipped out. At Marshall’s request, Menninger came up with a plan. This largely adopted the WW I approach, reinforced by the use of barbiturates and ether anesthesia if necessary for initial sedation of hysterical soldiers. In the most severe cases, other experimental treatments would be utilized like intravenous sodium pentothal, the “truth serum”, to draw out (and hopefully discard) the troubling traumatic memories of war. The echelon system would provide progressive evacuation of more serious cases and echelon 3 would be reinforced with special neuropsychiatric and convalescent hospitals where possible. All this sounded great, except for one thing. There were not nearly enough psychiatrists to execute the plan. So Menninger came up with the idea to train all medical officers in what he called “forward psychiatry”.

To do this he developed a diagnostic manual – Medical 203 (which after the war would become the basis of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or DSM). This was a structured approach to diagnosis and treatment, including the use of barbiturates, and a series of training films which included professional actors to illustrate what the medical officers might encounter. The fictional major in the film not so subtly reinforced that psychiatric treatment was a fundamental responsibility of all medical officers. The soldiers that were being treated were not abnormal people in normal time, but rather normal people trapped in an abnormal time. Every man has his breaking point was the message. These men were not “shell shocked”, they were suffering “battle fatigue”.

My father, in March, 1944 received the new training with other medical officers. He viewed the War Department Official training Film 1197. It had been produced on October 20, 1943 and titled: Early Recognition and Treatment of Neuropsychiatric Conditions In The Combat Zone.

The film began with a static slide that read:

““Any medical officer may be called upon to treat neuropsychiatric casualties. Because of the shortage of psychiatrists, the burden of early recognition and treatment of these casualties will fall on medical officers without special training. The attention of all medical officers , therefore, is invited to their responsibility for the mental as well as the physical health of military personnel.”

Early in the film, Menninger surfaced all the major objections doctors like my father might have by having the “Medical Officers” in the film raise questions with the “Major”. After a brief opening film segment showing an hysterical fictional patient with battlefield exhaustion, the major invites comments. Officers objections: 1) “I don’t see what else the officer (in the film) could have done. There doesn’t seem much point in keeping a patient like that on the battlefield”. 2) “Major, we’re going to be busy out there with patients who are really shot up and we won’t have time to monkey around with guys like that.” 3) “Major, I’m a surgeon. Looks to me like this is a job for psychiatrists.” 4) “That soldier must have been a misfit from the start to break down like that.”

The major’s response sets the record straight in pretty clear terms: “Gentlemen, you are not requested to treat these patients. You are directed to do so. May I acquaint you with a few statistics from recent campaigns. The size of the problem will startle you. These figures from Italy seem to indicate that 20% of all the non-fatal battle casualties were not wounded. They were suffering from neurosis. In Sicily the overall figure for the entire campaign was 14.9%. When you add up the easy and the hard days of the Tunisian campaign, you will find that 16% of all the non-fatal casualties were suffering from neurosis. In prolonged engagements where the going is really tough, we find that 30% to 50% of all men coming under your care in the divisional area are suffering from combat exhaustion…That means that 1 out of 3, or even 1 out of 2 soldiers coming under medical canvas does not have one drop of blood on him…..You are the members of the Medical Department and to you are entrusted the care of all of the sick. There are no specialists on the battlefield. If you say you are a surgeon and can only handle the surgically impaired, you have failed in your mission. Out in the mud, you’ve got to be a medical soldier and meet all comers.”

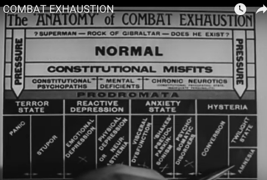

Now that he had my father’s and the others attention, they got down to business. A diagnostic tree with 4 conditions including hysteria, anxiety state, reactive depression, and terror state. Cutting across these four categories are the soldiers themselves who vary from being “Superman – Rock of Gibraltar” to “NORMAL” to “Constitutional Misfits.” The message is, “You will be dealing with all comers, and they will vary widely, but they all need your help.”

Then seamlessly, the major moves on: “…let us review some of the drugs available to us in narcosis therapy and chemical hypnosis available in your #2 Chest..”

1) Sodium Amytal: 9 to 12 grains (7 to 8 hours sleep) …wake, feed, bathroom…re-treat for total 24 hours. Also available IV (5 to 8 cc) (EI Lilly)

2) Nembutol: 4.5 to 6 grains (7 to 8 hours sleep)…in combat zones, massive doses are needed in treatment.

3) Phenobarbital: 4.5 to 6 grains (10 to 12 hours sleep)

4) Sodium bromide: dose and effect highly variable. Can be toxic. Used only if nothing else is available.

5) Pentothal IV: Short acting “truth serum” to surface suppressed memories.

6) Ether: Can be used to get unruly patients under control.

And in conclusion the Major delivers a clear instruction that would be actively followed by doctors in war zones, and become embedded in the practice of medicine for the next half century, “You have the facility of sedation and reassurance. Use them.”

At the end of the war, the doctors returned home with a distinct bias toward specialization and pharmacologic intervention – name it, treat it, cure it. Medical 203 morphed into DSM. By 1970, with the Medical-Industrial Complex now near fully funded by government research dollars, one in seven American adults, bruised by the Cold War, were on tranquilizers.

Tags: battlefield exhaustion > DSM > medical 203 > Military Medicien > overuse of psychiatric medicines > selective service WW II > shell shock > william menninger > WW II

ZIKA – What We Know and What We Don’t Know.

Posted on | February 5, 2016 | 2 Comments

CDC source

Mike Magee

How much do we know about Zika?

Natural History: Zika is a neurovirus transmitted across species by mosquitos. It was first described in the Zika Forest of Uganda, in 1947. Thus the name. Compared to two other viral infections endemic to the area – dengue and chikungunya – it was considered non-threatening to the population causing only minor symptoms in 20% of those infected. Within a short period of time, it spread to Asia, and then in 2007, jumped to the South Pacific islands, where an outbreak occurred in French Polynesia. In May, 2015, it first appeared in Brazil, a country of 200 million, where it spread rapidly.

How is Zika transmitted?

It’s transmitted primarily through a mosquito of the Aedes genus. These include the Aedes aegypti (yellow fever mosquito) and the Aedes albopictus (Asian tiger mosquito). The former is found in Florida and along the Gulf Coast, and the later can be found as far north as Chicago. They bred in any standing water.

It is now becoming clear that once a human has the virus it can be transmitted sexually to another human. Also a recent study found Zika may be present in mucous liquids raising additional questions regarding transmission.

Does Zika virus cause microcephaly in newborns and Guillain-Barre Syndrome (temporary paralysis in adults)?

Although there is no absolute proof that Zika caused outbreaks of these conditions, nor a strong theory on how the virus would accomplish this, the circumstantial evidence points to Zika as a causative agent in the recent outbreaks in both the French Polynesia and Brazil. In Brazil, where Zika is spreading rapidly, there have been 4000 cases in the past year of microcephaly in newborns coinciding with rapid spread of the virus. The normal number is 150 cases per year.

Where are there travel warnings for US citizens?

The travel warnings are being constantly updated at the CDC. Currently pregnant women are being discouraged from travel in South and Central America and in the Caribbean. Non-pregnant women who travel to these areas are being encouraged to take extra precautions to avoid becoming pregnant while traveling in these areas.

Are there tests for Zika?

Yes, Zika can be detected in blood and tissue samples. But it’s not easy, and requires a specialty lab and molecular identification. Development of simpler tests are underway. The current test does cross-react with dengue and yellow fever, so false positives have been a problem.

Why is there so much caution with pregnant women?

Obviously even the small possibility of a newborn developing microcephaly, which has no treatment and is usually accompanied by serious development problems, is frightening. Since 80% of those infected have absolutely no symptoms, it is difficult to be sure you have not been exposed. Also, it is not clear that the babies with microcephaly were delivered only by symptomatic mothers. At least some had no symptoms at all.

Does the virus hang around in the body, and potentially affect a baby conceived months after the original exposure?

The true answer is, we don’t know. But experts right now are saying the risk is “very, very low”.

Does the virus cross the placenta?

We don’t know, but if it causes microcephaly, it likely does in order to affect the developing brain in this way. Yellow fever and dengue viruses don’t cross the placenta, but rubella and cytomegalovirus can. The 1st trimester is when the fetus is most vulnerable.

Is there a treatment for Zika?

Since the symptoms are mild, anti-virals are not generally used. Work is underway on a vaccine.

Great resource article HERE.

Cross-Sector Partnerships and Public Health

Posted on | January 28, 2016 | 2 Comments

Source: NIH

Mike Magee

In an article this week in JAMA, titled “Aspirations and Strategies for Public Health”, the authors explore how best to position the role of Public Health in advancing population health. Three points were especially noteworthy.

1. “Public health must engage the social, political, and economic foundations that determine population health.”

2. “The conditions that make people healthy often are outside what have historically been considered the remit of the health professions: health improvement now requires participation in politics and social structures.”

3. “..public health advocates must work with actors across government, academia, industry, and not-for-profit sectors to achieve the goals of public health.”

These insights reinforce two important truisms:

2. Cross-sectors partnerships are essential.

Complex forces at work over the past two decades have created a myriad of social, economic and political challenges that demand cooperative and collaborative solutions. Such cross-sector partnerships presume clear role delineation, well defined strategies and objectives and evolving relationships that challenge historic checks and balances.

The desire on the part of government, academics, non-governmental organizations and industry to forge new partnerships reflects the common belief that no one sector can address such complex challenges in isolation. The rapid advance of technology has supercharged the environment accelerating globalization, regionalization and the rate of change in social institutions while virtually disintegrating geographic boundaries. Success in forming stable and productive cross-sector relationships will largely determine the extent to which we are able to ensure societal justice and progress.

The rapid emergence of new technology has conspired to eliminate previously well-defined sector boundaries. On a most fundamental level, these previously heavily segregated sectors now possess, in varying degrees, a common language and set of tools. In addition, information and knowledge are no longer subject to reliable isolation whether by geography, class, gender, race or religion. Finally, the acquisition and implementation of new information technologies have ignited a highly compressed, cross-sector and globally competitive exercise in process redesign that has fundamentally changed the way we communicate and do business with each other, and in the process ramped up expectations for progress absent a fundamental alteration in our human capacity to absorb change without destabilizing our societies.

Government, business, academics, and non-governmental organizations today confront a complex series of public challenges that no one sector can address in isolation. Each sector has well defined historic purposes, roles and strategies for success. Appreciation of these unique traditional assets is a starting point in our common movement toward mutual appreciation and partnership.

Industry has focused on business performance, the creation of wealth, the discovery of new markets, the expansion of social engagement, the delivery of customer service, and expanding and aligning philanthropy with core mission. Government has focused on purpose and governance, redefining basic roles and responsibilities, exploring centralized and decentralized approaches, tapping cross-sector expertise to expand efficiency, and developing skills as bridgers and collaborators in an effort to share responsibility for creation and execution of sound policy.

Academics have traditionally focused on a mission of service, education and research. Today they confront diminishing resources and increasing demands for service and social action. In response, they have emphasized reengineering of patient care processes to accomplish operational efficiencies, and constructive approaches to partnering emphasizing trust and transparency, with a constant eye on institutional integrity.

Non governmental organizations (NGO’s) have focused on shaping attitudes and behaviors of government, industry and academics. This relatively new mission has been layered upon one of traditional service and activism directed at specific concrete objectives with a high degree of immediacy. They have focused on virtual communications, organizational building, and campaign execution skillfully leveraging new low cost information technologies and high media credibility.

Beyond a common understanding of the strengths and capabilities of each sector, and the desire for collaboration reflected in a willingness to mutually plan, to align goals and objectives and to share risk, there remains the issue of environmental readiness. What are the factors that must be in place to ensure success?

First, if it is true that all politics are local, so too are all successful cross-sector partnerships in so far as they acknowledge in their planning, design and management the realities of time, place, people and institutions in the target geography.

Second, in any cross-sector initiative in health, there should be some level of representation from each of the four sectors. The partners must have a well-defined common need or public purpose that unites them. What is that common passion?

Third, the proposed project or solution must be right sized to the problem or challenge at hand. Too small and the effort will lack resources to ensure measurability and sustainability. Too large and the effort will create structure without solution.

Fourth, human conditions must be right. This includes identifiable optimistic leaders with the time and willingness to commit and a reservoir of good will among the players to support both innovation and implementation of the common vision, the structural integration, the joint governance and ongoing civic engagement.

Fifth, there needs to be accurate information and baseline data that clearly defines the challenges and serves as a grounding for future reasonable outcomes. It is not enough to marshal human resources. There must be an established organizational capacity, processes, and oversight to ensure that the human effort translates into a highly coordinate and effective service result.

The social, economic and political challenges accompanying our rapidly changing and fundamentally transforming global environments have created unique social challenges that demand cross sector solutions. These new models of collaboration are uniquely evolving and being shaped by the transformational forces at work in our modern society which demands both competency and equity.

In pursuit of these new partnerships in the health sector, there should be a bias toward action, early organization and prevention, health consumerism and relationship based care, elimination of health disparities, and an integrated vision of health as the leading edge of development with an emphasis on sustainability.

Government, business, academics and non-governmental organizations are increasingly overlapping in the areas of social purpose. The ability to organize their varied and often complimentary skills and resources will significantly benefit society. Such collaboration will be increasingly necessary to address the health care needs of an increasingly interconnected global society.

Audit for the New Health Care Professional

Posted on | January 21, 2016 | Comments Off on Audit for the New Health Care Professional

Mike Magee

In the shift from old models of paternalistic, reactive and interventional care to anticipatory, team-based, inclusive preventive care, health professionals need to think more strategically about their roles as leaders of the health delivery team.

What is health really but the maximization of human potential? How do we best connect patients to information, community resources, extended family and each other? What are the social determinants of health, and what are the quality of these resources in your own patient catchment area? Who is taking the family lead in each of the families you care for, and how could this person become enfranchised as a member of your care delivery team? And finally, what is your care philosophy, your strategy for delivering high quality humanistic care?

Beginning January 27th, I’ve teamed up with BHG360, a leading provider of healthcare financial solutions. The 5-part series to appear on the BHG360 site is a personal audit for the modern, progressive health professional, designed to consider and improve the fundamental underpinnings of a successful, holistic, preventive health care practice. The series includes:

- “The New Patient – Health Professional Relationship: Wellness Walking describes the latest research regarding the power of the patient-physician relationship and its role in forming social capital in healthy societies. Three growth areas for clinicians are highlighted – active listening, joyfulness and role modeling.”

- “Health Information Technology: An Underutilized Resource makes the case for health information technology as a humanizing force in health care. Clinicians are provided five questions to explore whether their attitudes toward technology are progressive and constructive.”

- “The Role of a Home Health Manager: Inclusion in the Health Care Team considers a modern approach to all of the human resource aspects of family health care. It defines health as human potential; considers the emergence of 4 and 5 generation families with competing needs and limited resources; and advocates for active inclusion of a lead family member (Home Health Manager) as an active member of the health care team.”

- “Roadmap to Health: Integrating Community Resources explores the role of community resources in the modern practice of preventive health care. The reader is introduced to Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s ‘County Health Rankings & Roadmaps’ which allows practices at any location in the U.S. to explore what community resources are available to their patients and how their patient population ranks statewide on a range of public health outcome measures.”

- “The Secrets of Humanistic Care explores the basics of team-based, humanistic care. Using a NICU team as an example, the principles are applied to outpatient settings with a focus on inclusion, knowledge and accessibility.

Take a moment to visit BHG360 and review their unique offerings.