The Catholic Playbook on Contraception, Circa 1950…and The Doctor’s Role In It.

Posted on | October 10, 2017 | 1 Comment

A Little Sister & Friend

Mike Magee

Who knew – The Little Sisters of the Poor’s new best friend would be Donald Trump?

Catholic institutions were first in line to challenge the ACA, followed by a motley crew of Obama haters who persisted for two terms before being exposed as having no legitimate health policy alternative. And now the Trump administration says they don’t have to obey Obama era rules in their organizations and cover contraceptive costs for their employees.

For anyone who has followed the Catholic Church’s embrace of birth control as a defining issue over the past 100 years, the Little Sisters benign expressions married with legal tactics should come as no surprise.

I know whence I speak. My doctor father inherited his mother’s devotion to the Catholic Church. Returning from WW II, he embraced the rituals and the sacraments. He would sink into deep contemplation at Sunday mass each week. And he loved being the selected doctor to the priests and nuns of the parish. My mother loved the structure and the concrete set of rules and beliefs that provided a scaffold and creed to build a life around.

Together they were a model Catholic family of the 1950’s – he a Catholic doctor serving mostly 1st generation Catholic immigrants, and she the mother of twelve Catholic kids.

As war veterans were returning, and the baby boom igniting, the Catholic Church doubled down on its ban of contraception. Science had progressed during the 1940’s and the basic understanding of fertility and manipulation of the ovulatory cycle had arrived.

The American Catholic Church and its’ leadership could easily predict the next step. It was only a matter of time before pharmaceutical companies and their allied physicians would figure out how to manipulate and destroy this miraculous system. Clearly, God’s right to decide when and where to deliver His children was under attack, and the Church must defend, defend, defend.

As Pope Pius XI had said in his famous Encyclical, Casti Connubi, on December 31, 1930: “…every attempt of either husband or wife in the performance of the conjugal act or in the development of its natural consequences which aims at depriving it of its inherent force and hinders the procreation of new life is immoral; and that no ‘indication’ or need can convert an act which is intrinsically immoral into a moral and lawful one.”

With modernity crushing in from all sides, the Church decided to embrace what was essentially a defensive move – the new “Rhythm Method” which at least emphasized restraint and periodic abstinence, and might dampen the march toward use of horrid preventatives, paganism, and sins of the flesh.

But who would teach and proselytize this new method which combined temperature based predictions of ovulation and fertility with voluntary abstinence? The answer was Catholic doctors like my father.

![]()

![]()

The vehicle the Church selected to deliver instruction on Catholic family planning was described thoroughly in the Archdiocese of Chicago’s 203 page book entitled The Basic Cana Manual. Cana and Pre-Cana Conferences were designed to be lay led meetings, with parish priest in attendance, focused on both marriage preparation and marriage renewal. My parents, as selected lay leaders, beginning in 1949, read the book from cover to cover, and participated as leaders in delivering the messages.

For them, it was a night out, free of the children; an opportunity to enjoy each other’s company, and to perform “on stage” which was a shared interest. They were not particularly worried or concerned about the dogma, or communicating the fear piece well. Sin and hell were not really their thing, any more than the “Sister is always right” mentality of most Catholic parents who sent their kids to Catholic schools. Their major mutual interest was in marital love and fidelity, the joy of commitment in good times and bad, and the rewarding challenges of managing very large families.

In any case, they found a lot to like in The Basic Cana Manual. The words on page 3, penned by the Reverend Walter J. Imbiorski, who presumably was chaste and celibate, struck a realistic and empathetic tone. “We fall in love and we get married and presently disenchantment sets in, the sense of adventure leaves us. And even this is no particular surprise. Doesn’t it happen to everybody? We share, day after day, all that goes into the common effort, the continuing adventure, of establishing and sustaining a family. But what does it add up to? We go through all the motions of marriage, but how involved are we?…Cana is dedicated to restoring that poetry which is the Divine idea of man and woman and marriage. Cana is really a meditation on man and woman and all that is implied in the words ‘one flesh’.” And a few sentences later, the smooth and gentle segue, “Once reverence for the supreme wisdom of the Creator of nature is learned, it becomes less of a temptation to prefer human calculations, easier to base married life on words of the marriage exhortation, ‘The rest is in the hands of God.’”My parent’s role was quite clear and patriotic. “The role of the layman is especially important because we live in a world largely and progressively secularist. It doesn’t deny God or His Church; worse – it ignores them. The Catholic Laity must act to resist the pressures of secularism and worldliness. In America to stand still is to be engulfed”. (104)

As for my father’s second role as Catholic physician, the doctor got a whole 13 page chapter to himself titled “The Doctor in Pre-Cana”. Pre-Cana was the title given to the conferences required of all Catholic couples before being married in the Church. It was at these events that the delicate issue of family planning would be raised.

The instructions in the chapter were quite explicit. The chapter opens with, “The subject of the doctor’s talk in Pre-Cana should be sex, maleness and femaleness, in its broadest and most Christian sense. His approach should be one of respect and reverence toward this mystery – ‘man’s greatest glory in the temporal order’.” There were some cautions as in “There is no necessity of exposing any of the audience to the danger of sinning by an overly-exciting lecture. On the other hand, he must not be apologetic or shy, but after thorough preparation he should speak forth directly and with authority as a Catholic and a doctor.”

Rhetorically again, the Manual asks, “Just what should the doctors attitude towards sex be?” The answer: “The principle that underlies all others is that sex has its primary purpose the procreation and education of the child. Secondarily, it is the most unique expression and symbol of the love of two persons, an intimate act of knowing and giving in which they complete and satisfy each other on every level. This latter purpose, however, is obviously secondary to, and dependent upon, the great reality of the first.”

The Church makes clear its intention to use doctors, in the same manner as pharmaceutical companies, as “learned intermediaries”, with the power to extend and legitimize the Catholic Church “brand”. It reads, “The doctor’s role on the Pre-Cana team is to add his authority, personal and professional, to the teachings of the Church. Speaking with warmth and concern, and yet with a degree of clinical detachment, he can properly take up some areas that priests or layman can avoid. Secondly, his prestige, though often over-rated, can be used to advantage… Finally the doctor can authoritatively counteract many of the popular pseudo-scientific ideas about sex that are gaining currency.”

A few paragraphs later, there is a chilling disclosure reminiscent of the moral dilemma current physicians face with corporate conflicts of interest. It reads, “The doctor has status in our society. He is a combination of scientist and mystic healer. His words carry great weight. You will likely never suspect the tremendous good you will do for Pre-Cana” (read “for pharmaceuticals or medical devices”).

Instructions in the 1957 book on the “Rhythm Method” include considerable verbal gymnastics and “model language and messaging”. First choice, no protection. Second choice, rhythm if you must. Third choice, don’t let a doctor talk you into a “family limitation”.

Fearful facts are provided to defend this approach. “First of all, you don’t know whether you are able to have children at all. Statistics show that about 15% of you will have no children, regardless of what you do, and another 9 or 10% will have at the most one child…It is more difficult to have children than most believe. There are only about 25 to 30 hours in a month when a conception can take place. Therefore, to practice rhythm in the early years of marriage,when you are most fertile, might perhaps deprive you of the blessing of a child.”

And in parenthesis, this special instruction for the doctor: “(The physician must make clear that he is not condemning the use of rhythm by newlyweds on moral grounds, but because it is biologically and psychologically unwise, i.e., it will deprive them of much happiness and success they might achieve in their marriage….If later on the use of rhythm is decided upon it might be recommended that the couple consult their doctor. In passing it might be mentioned that, unfortunately, some doctors are too ready to prescribe family limitations for presumed medical reasons, merely to comply with the desires of the couple.)”

Through the years, my father continued to advance the cause of the “rhythm method” not only to his patients, but also to his daughters and future daughter-in-laws. As a result, my parents eventually had 41 grandchildren, and there would have been more if their children hadn’t finally figured out for themselves what they were doing wrong.

The fact that we were all highly educated, and enjoyed the sense of security of our own personal family safety net thanks to my father’s success as a doctor, tended to accentuate the blessings of our children and soften the occasional bumps and bruises we experienced along the way. Most of our marriages survived. Our families had adequate housing in clean neighborhoods, good nutrition, good schools, reasonable and manageable stress, modest disease burdens, and little hopelessness. Others who my father cared for, whose lives were far less secure, were perhaps not so lucky.

Tags: aca > Cana Conference > Catholic Chrurch > contraception > Obamacare > repealing the ACA > The Basic Cana Manual > Trump care > womens health

Geographic Health Disparity for Abortion Access.

Posted on | October 4, 2017 | Comments Off on Geographic Health Disparity for Abortion Access.

The Story Behind The Pharma Savings Coupon.

Posted on | October 2, 2017 | Comments Off on The Story Behind The Pharma Savings Coupon.

Mike Magee

As I’ve said before, complexity is the friend of the Medical Industrial Complex. Whether hospital, insurer, organized medicine, pharmaceutical or government agency, profitability, market advantage and career advancement can be found in the cracks of the deliberately Byzantine network.

For those intent on regulating or managing the American system as it is, just understanding and unraveling the opaque morass can be a full time job.

Consider the case of US pharmaceuticals and coupon cards. Before I go there, here are a few supply chains facts you need to know.

1. Quantity: There are roughly 4 1/2 billion prescriptions filled each year with about 90% of them fulfilled with generic drugs.

2. Consumption: Just under 50% of American residents have filled 1 prescription in the past 30 days, and 10% of the population takes 5 or more different prescription drugs.

3. Construction: Most of the raw materials for products of US-based drug multi-nationals are made overseas by a $46 billion dollar manufacturing conclave .

4. Distribution: Once the company produces an individual drug, it does not go to a pharmacy outlet directly. Instead it is shipped to a U.S. distributor. 85% of all drugs consumed by Americans go through one of three giant distributors – AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson – which received $378 billion for their services in 2015.

5. Retail: Most Americans get their prescriptions filled at one of the 60,000 pharmacies, either in person or by mail order. 38,000 (63%) of the outlets are part of retail chains, and 22,000 (37%) are independents. All told, the retail pharmacies collect about $365 billion in revenue a year. Chains dominate with just 15 (including CVS, Walgreens, Walmart and Express Scripts) controlling 74% of all retail income. They collect 62% of this in person and 38% by mail order.

6. Who Pays?: Americans pay for their drugs through a confusing partnership mix and match designed by varied insurance companies. This requires negotiating deductibles, coinsurance and copays. For the total paid out, 42% comes from private plans, 30% from Medicare (Part B and D), 10% from Medicaid, and 14% from individual themselves.

7. Cost Control: Insurers use Pharmacy Benefit Managers to hold down their costs. PBMs are big business and of the biggest three one is owned by the pharmacy chain mega-giant CVS (CVS Caremark), a second by insurer UnitedHealth Group (UnitedHealthOptum), and a third geared toward mail order (Express Scripts). Together these three control 72% of the PBM market.

As the Martin Skreli’s of the world increasingly stuck their fingers in the eyes of vulnerable Americans, Big Pharma looked for strategies to counter the bad PR. One strategy was to offer coupons to offset the cost of their brand name drugs. But usually, the offer was extended on products that already had a low cost generic substitute available on the market.

Generics in general are about 80% cheaper across the board than brand name counterparts. But when it comes to coupons, the critical thing you need to understand is that payment for the prescription is a team effort. You pay but so does your insurer. And often, coupons play one off the other. For example, if a coupon allows you to get a 30 day supply of a brand name drug for $4, when a generic costs you $10, few opt for the generic. But behind the scenes, two things are happening. First, the drug company has a free hand to raise the brand drug’s overall price because patients aren’t complaining. Why should they? Their cost is fixed at $4. But insurers often pay a percentage of the total cost, so their paying a premium. Plus the overall cost of the generic was much lower to begin with.

“Who cares?” you might ask. “It’s just the insurer.” True, but eventually that cost will be recovered in your premiums. Estimates are that off-patent brands that use coupons to compete with generics increase their sales by over 60%. And these coupons add several billion dollars in extra spending a year to our health care system.

This kind of manipulation and greed within the cracks of our uniquely entrepreneurial health care system are part of the reason why increasing numbers of Americans are saying enough is enough, and flirting with single payer simplicity and transparency.

By the way, Medicare bans the use of drug coupons.

Tags: drug costs > drug coupons > drug savings cards > drug supply > pharmaceutical supply chain

Soul Searching and Deep Thinking – A Socratic Moment

Posted on | September 28, 2017 | Comments Off on Soul Searching and Deep Thinking – A Socratic Moment

Mike Magee

You can say what you want about America’s current trajectory, but one thing’s for sure – there’s a lot of soul searching and deep thinking going on. Just this morning, I came across three different pieces – in The New Yorker, the New England Journal of Medicine, and the The New York Times – all deep, deep, deep!

I also came across the following quote attributed to Socrates in the April 28, 1927 issue of The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal (to become the NEJM one year later) : “Men of Athens, I have never yet studied medicine, nor sought to find a teacher among our physicians; for I have constantly avoided learning anything from the physicians, and even the appearance of having studied their art. Nevertheless I ask you to appoint me to the office of a physician, and I will endeavor to learn by experimenting on you.”

The New Yorker piece was written by Atul Gawande who cued up the question: “Is Health Care A Right?” Atul, a physician and public health expert, had traveled back to his conservative, bedrock American home of Athens, Ohio, to track down childhood friends for answers to his existential query. Here are a few of the honest revelations/biases/beliefs/insights.

From The New Yorker (Atul Gawande):

“One person’s right to health care becomes another person’s burden to pay for it.”

“Everybody has a right to access health care, but they should be contributing to the cost.”

“I am becoming more liberal. I believe that people should be judged by how they treat the least of our society.”

“A right makes no distinction between the deserving and the undeserving, and that felt perverse.”

“Here self-reliance is a totemic value.”

“The notion of health care as a right struck her as another way of undermining work and responsibility… ‘I’m old school, and I’m not really good at accepting anything I don’t work for.’ ”

“But then we talked about Medicare, which provided much of her husband’s health care and would one day provide hers. That was different. ‘We all pay in for that,’ she pointed out, ‘and we all benefit.’ … There is genuine reciprocity.”

“Medicare was less about a universal right than about a universal agreement on how much we give and how much we get.”

“…rights are as much about our duties as about our freedoms.”

“…‘basic rights’ are those which are necessary in order for us to enjoy any rights or privileges at all…. basic rights include physical security, water, shelter, and health care… the critical question may be how widely shared these benefits and costs are.”

“…everyone has certain needs that neither self-reliance nor the free market can meet… When people get very different deals on these things, the pact breaks down.”

“ ‘I think the goal should be security,’ he said of health care. ‘Not just financial security but mental security—knowing that, no matter how bad things get, this shouldn’t be what you worry about.’ ”

“We don’t worry about the Fire Department, or the police. We don’t worry about the roads we travel on. And it’s not, like, ‘Here’s the traffic lane for the ones who did well and saved money, and you poor people, you have to drive over here.’ ”

“What we agree on, broadly, is that the rules should apply to everyone.”

From the New England Journal of Medicine (Ziad Obermeyer, M.D., and Thomas H. Lee, M.D.):

“The complexity of medicine now exceeds the capacity of the human mind…”

“Every patient is now a ‘big data’ challenge…”

“The first step toward a solution is acknowledging the profound mismatch between the human mind’s abilities and medicine’s complexity.”

“If medicine wishes to stay in control of its own future, physicians will not only have to embrace algorithms, they will also have to excel at developing and evaluating them, bringing machine-learning methods into the medical domain.”

“Machine learning has already spurred innovation in fields ranging from astrophysics to ecology… but experts in the field — astrophysicists or ecologists — set the research agenda…”

“Algorithms that learn from human decisions will also learn human mistakes, such as overtesting and overdiagnosis, failing to notice people who lack access to care, undertesting those who cannot pay, and mirroring race or gender biases.”

From the New York Times (Thomas L. Friedman) :

“We’re… going from an interconnected world to an interdependent one… a world of webs where you build your wealth by having the most connections to the flow of ideas, networks, innovators and entrepreneurs.”

“… connectivity leads to prosperity and isolation leads to poverty.”

“We’re moving into a world where computers and algorithms can analyze….optimize….prophesize…customize…digitize…automatize.”

“Any company that doesn’t deploy all six elements will struggle, and this is changing every job and industry.”

From me:

I’ll spend the rest of the day considering how these three pieces inform each other.

Tags: and Thomas H. Lee > Atul Gawande > health reform > hearth care rights > m.d. > NEJM > The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal > The New York Times > The New Yorker > Tom Friedman > US health policy > Ziad Obermeyer

Global Burden of Disease Update – U.S. Mortality 58th.

Posted on | September 25, 2017 | Comments Off on Global Burden of Disease Update – U.S. Mortality 58th.

The Lancet just updated Christopher Murray’s longitudinal study on Global Burden of Disease. Now entering its 20th year, it continues to show the advance of chronic disease over communicable disease as a source of mortality and morbidity(in 3 out of 4 cases).

In the latest rankings, the US finished 24th overall but has dropped to 58th in life expectancy, its lowest ranking in 45 years. Our life expectancy has been essentially flat since 2010. The major chronic disease killer varies by national income. In high wage countries like our own heart disease remains the major killer, fueled in part by obesity. In low wage nations, respiratory conditions, fueled by environmental degradation and cigarette smoking, lead the way.

As for communicable diseases, many nations have made progress in under-5 mortality, especially from malaria. Survival across all nations is not necessarily accompanied by “good health”. The evil triplet is obesity, mental illness and violence.

This Medscape interactive graph has all the facts and figures. The size of the box shows its relative contribution to the global burden of disease. Going from orange to blue shows increasing incidence population-wide over the past decade.

Overall, the world’s population is living longer. But in some ways that demands that our health care systems be more efficient and effective. Why? Because individual burden of disease and the cost of managing this burden grows as we age. Rises in disability from arthritis to hearing loss, from COPD to cardiovascular disease, will predictably challenge inefficient systems as in the US. If anything, our system will strain further without reform.

Tags: Christopher Murray > Global Burden of Disease > lancet > US life expectancy.

Academic Medicine – What’s To Become of the Triple Mission Under Universal Health Care?

Posted on | September 18, 2017 | Comments Off on Academic Medicine – What’s To Become of the Triple Mission Under Universal Health Care?

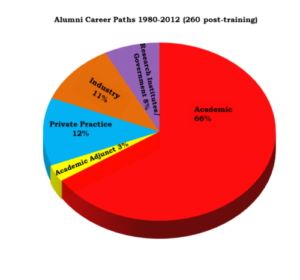

Hopkins Alumni Careers 1980-2012.

Mike Magee

A New York Times banner headline in 2016 read, “Harnessing the U.S. Taxpayer to Fight Cancer and Make Profits”. It documented the unusual partnership between Kite Pharma, a cancer immunotherapy start-up run by serial entrepreneur, Arie Nelldegrun, and the U.S. government. The underlying immunotherapy research was the output of Nelldegrun’s mentor, Steven Rosenberg, at the National Cancer Institute (N.C.I.). Taxpayers contributed about $10 million to Rosenberg’s lab since 2012. Kite kicked in an additional $3 million a year to accelerate drug development by the N.C.I., but not for free. They own rights to future profitability. In some of the deals (there have been 8 contracts since 2012), Kite receives patent use in return for promises of royalties paid to the N.C.I.

All this proceeds as daily we absorb case after case of over-marketing, over-pricing and over-selling of drugs and medical devices into an American market that consumes them at twice the rate of most civilized nations. Scientific progress appears to have been uniquely decoupled in our nation from human progress. How did we get here?

Since Vannevar Bush presented his “Science the Endless Frontier” to President Truman, and the President insisted on strong government control of federally sponsored research, there had been a prohibition on private ownership of patents that emerged from research discoveries supported by federal grant dollars.

So the federally funded discoveries and their patents sat in the government vaults, largely unused and undeveloped. In fact, by 1978, with the economy in chronic recession, 28,000 scientific patents had accumulated. Over the years, fewer than 5% had been commercialized. At that time, Indiana’s Purdue University was sitting on a number of new health related discoveries that had emerged from their research departments, supported by NIH grants. They approached their senator, Birch Bayh (D-IN), to help them control their patents and profitability.

At about the same time, the lobbyists discovered that Bob Dole had been exploring the same legislative territory. Bob was delighted to conspire with Bayh on a possible fix for the problem. Together they fashioned a solution that would allow individuals, small businesses and academic institutions to maintain ownership of their own intellectual property, even if it derived from government grant money.

The results of the Bayh-Dole Act were dramatic, at least for health care institutions. While 380 patents were granted to them in 1980, that number soared to 3088 by 2009. Those patents, now under the control of individual scientists and their parent academic institutions, were subsequently licensed to corporations for the development of a range of products and applications. According to one estimate, the resultant impact on the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) reached $47 billion in 1996, and soared to $187 billion a decade later.

Since 1980, over 2,200 new companies have appeared and generated more than 1000 new products. As important, the new technologies spawned entirely new industries in the United States including the field of biotechnology.

Of course, over time, it became clear that the legislation did have some unintended consequences. The licensing bounty for industry and academics was not insignificant. It rapidly grew from just over $7 million in 1981 to $3.4 billion by 2008. And major pharmaceutical companies were at the top of the food chain. Over the first three decades with the Bayh-Dole Act in place, 154 new drugs were approved by the FDA with worldwide sales attributed to these products of $103 billion.

This led The Economist, in 2005, to headline their reappraisal of the Bill, “Bayhing for blood or Doling out cash?”(7) As the article states, “Many scientists, economists and lawyers believe the act distorts the mission of universities, diverting them from the pursuit of basic knowledge, which is freely disseminated, to a focused search for results that have practical and industrial purposes.”

What’s to become of Academic Medicine’s triple mission – medical education, patient care and research? Giant, for all practical purposes, “for-profit” research institutes increasingly marginalize patient care and medical education just when we need leadership in these areas the most. As a nation, we are attempting to correct historic health care missteps in universality, efficiency, transparency, effectiveness and justice.

In this modern era, the triple mission is delivering an integrative and at times collusive professional career ladder, but not much else. What should Academic Medicine leadership and governance look like within a universal health care system?

Tags: Bayh-Dole Act > health care research > medical patents > medical research > science the endless frontier > vannevar bush

Pharma Patents – A Good Bet For Casino Heavy Native Americans.

Posted on | September 11, 2017 | Comments Off on Pharma Patents – A Good Bet For Casino Heavy Native Americans.

The Latest Pharma Campus?

Mike Magee

In the immediate aftermath of WW II, the U.S. government decided to join hands with industry and academia and fund a campaign to “defeat disease” as they had defeated the Nazi’s. Defeat disease and health will be left in its wake was the thinking of the day. What they could not have predicted was that a native American tribe in Upstate New York would ultimately be one of the recipients of this food chain.

Nor would the starch collar academic William Wardell, the inventor of the phrase “drug lag” in 1973 that ultimately unleashed four decades of FDA liberalizing legislation, have predicted its long term impact. While these actions arguably have accelerated scientific progress, in many ways they’ve left human progress to fend for itself.

But this is America’s Medical-Industrial Complex where profit trumps patients at every turn. The latest episode began early this year when a Dallas law firm, Shore Chan DePumpo, successfully defended their client, the University of Florida, in a medical device patent dispute with Covidien. They claimed that the state owned institution had state soverign immunity, and thus its patent could not be challenged. They went before a specially liberalized administrative-review panel created to shield industry from the trials and tribulations of normal patent law and they won!

What happened next was predictable. The law firm went trolling for their next client. As one legal expert noted, “Indian tribes have sovereignty that is stronger than states.” So they identified an Upstate New York tribe, the St. Regis Mohawks, that had done a patent protection deal with a Tech firm. They were anxious to continue to diversify being over-weighted in Casinos. Now all that they needed was a desperate partner with deep pockets. They found that in Allergan who’s #1 product is Botox. But right behind it is their billion dollar winner Restasis – for desperately dry eyes.

As patent expiration on Restasis approached, the company filed six extra patents of dubious merit a year or two ago that were accepted by the new and very accommodating Patent Trial and Appeal Board. This would have protected Allergan against generic intrusion till 2024. But again predictably, the litigious generic company, Teva, challenged the patents.

The patent gold rush is not a new phenomenon. It’s origins date back forty years. In 1978, five years after the “drug lag” accusation had first surfaced, with the economy still lagging, 28,000 federally controlled scientific patents had accumulated and sat largely idle. Historically, there had been a prohibition on private ownership of patents that emerged from research discoveries supported by federal grant dollars. As the thinking went, such discoveries, supported by public dollars, should be available to all, without the patent restrictions of a private company. But in reality, the lack of ownership of the intellectual property, and any market products or applications that would derive from it, frightened away private investors.

Over the years, fewer than 5% of these federal patents had been commercialized. At that time, Indiana’s Purdue University was sitting on a number of new health related discoveries that had emerged from their research departments, supported by NIH grants. In face of the country’s “economic doldrums”, they decided to invest a bit of money on lobbyists to see if they might somehow wrest control of the patents, and future profitability tied to their inventions. They approached their senator, Birch Bayh (D-IN), and were delighted to see that he was receptive.

At about the same time, the lobbyists discovered that Bob Dole had been exploring the same legislative territory. With Dole’s support, the technology transfer legislation swept through the Senate Judiciary Committee with unanimous support. Bayh then negotiated the Bill’s inclusion in the House’s version. With just a few days left in his single term Presidency, Jimmy Carter signed the bill.

The results were dramatic, at least for health care institutions. While 380 patents were granted to them in 1980, that number soared to 3088 by 2009. Those patents, now under the control of individual scientists and their parent academic institutions, were subsequently licensed to corporations for the development of a range of products and applications. According to one estimate, the resultant impact on the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) reached $47 billion in 1996, and soared to $187 billion a decade later. Since 1980, 2,200 new companies appeared and generated more than 1000 new products. As important, the new technologies spawned entirely new industries in the United States including the field of biotechnology.

As an economic change agent, few legislative actions could compete with this one. Of course, over time, it became clear that the legislation did have some unintended consequences. The licensing bounty for industry and academics was not insignificant. It rapidly grew from just over $7 million in 1981 to $3.4 billion by 2008. And major pharmaceutical companies were at the top of the food chain. Over the first three decades with the Bayh-Dole Act in place, 154 new drugs were approved by the FDA with worldwide sales attributed to these products of $103 billion.

This led The Economist in 2005 to headline their appraisal of the legislation, “Bayhing for blood or Doling out cash?”(67) As the article states, “Many scientists, economists and lawyers believe the act distorts the mission of universities, diverting them from the pursuit of basic knowledge… it makes American academic institutions behave more like businesses than neutral arbiters of truth…”

What will happen next on the Indian reservation is anyone’s guess. Chose your favorite – Teva or Allergen. In American Medicine’s Wild Wild West, the winner will be either bad or worse. And not one American will be the healthier for it.

Tags: Bayh-Dole Act > intellectual property > medical-industrial complex > patent protections > patents > pharmaceuticals