2018 – The Year of Dr. King.

Posted on | January 2, 2018 | Comments Off on 2018 – The Year of Dr. King.

Mike Magee

We awaken this morning, on this sacred day that honors Martin Luther King Jr., to the continued reverberation of racist and profane commentary days ago from his polar opposite, a man who adds insult to injury by bragging that his vile actions will help him in the polls.

And yet 2018 has the potential to be a monumental turn-around year for America, a year when we stare our true culture in the face, and decide to embrace health and well-being.

Fifty years ago, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. warned that excessive materialism, militarism, and racism were “inseparable triplets”, and that our nation required a “revolution of values…a restructuring of the very architecture of American society.” Recently, conservative columnist David Brooks said as much with these words, “The first step in launching our own revival is understanding that the problem is down in the roots.”

Our culture is so blatant in its disrespect for human and planetary health that it’s simply hard to ignore any longer. Dr. King recognized this core truth a half century ago when he said, “We are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality tied into a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly. We are made to live together because of the interrelated structure of reality.”

With new leadership in 2018, we might begin the long transformative step toward a healthier culture.

On gun violence:

Our’s is a country that not only allows and promotes guns, but also now limits federally funded research on gun violence and has attempted to muzzle physicians who wish to discuss gun safety with their patients. There were 36,161 motor vehicle crash deaths in 2015. That’s bad, but it’s 91 fewer deaths than caused by guns that year. We’re killing 100 people a day with our guns, 60% of which are suicides – successful 90% of the time when a gun is the instrument.

On planetary health:

We just marked the 25th anniversary of the landmark “Warning to Humanity”, a consensus document filed by 1,700 scientists on global warming. Trump’s pull-out of the Paris Accord aside, the group now 15,000 scientists strong from 184 countries, just published an update in the journal BioScience. Lead scientist, Henry Kendall, states, “If not checked, many of our current practices put at serious risk the future that we wish for human society and the plant and animal kingdoms, and may so alter the living world that it will be unable to sustain life in the manner that we know.”

On childhood obesity:

Futurists now predict that the obesity rate in today’s children, when they hit adulthood, will be 57%. And with this, soaring rates of diabetes and heart disease surely follow, while health resources are diverted to elusive “scientific progress” as American “human progress” continues in steep decline.

On gender inequality and abuse:

Of course, the list goes on – consider the mind-boggling short and long-term implications of what appears endemic sexual abuse in and out of our workplaces. And that doesn’t even begin to address the fact that we seem to have managed to elect as our president a man who is a confessed serial sexual abuser.

Yet, to his credit, President Trump, with his vile labels, has done nothing more than force us to face, in sharp relief, our true selves and the “inseparable triplets” Dr. King described now 50 years ago. The time has come to fulfill his dream of a healthier America. 2018 is the year, and elections are just a few short months away.

Tags: american culture > childhood obesity > culture and health > gun violence > Paris Accord > planetary health > sexual abuse > Social determinants of health > trump

Santa’s Message on Health

Posted on | December 25, 2017 | 8 Comments

Mike Magee

Mike Magee

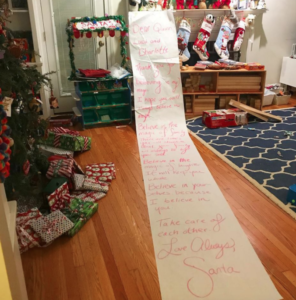

“Dear Quinn, Luca and Charlotte,

Thank you for believing in my magic. I hope you will always believe in magic.

Believe in the magic of family. There are times you will stumble, but your family will always be by your side.

Believe in the magic of laughter. It will keep you whole.

Believe in yourselves because I believe in you.

Take care of each other.

Love always,

Santa”

When I read this message to three of our ten grandchildren on this snowy Christmas morning in New England, it spoke to me of strength and resilience, of love and solidarity, of healthy minds and bodies and spirits.

This coming year will be a critical challenge for all Americans. How will the American family respond? How do we make America healthy again? I cling to Santa’s final words – “Take care of each other.”

The MIC Circular Firing Squad

Posted on | December 16, 2017 | Comments Off on The MIC Circular Firing Squad

Mike Magee

If you want to see the Medical-Industrial Complex (MIC) in full “circular firing squad” mode, simply check out the recent Energy & Commerce Committee hearings on soaring drug prices hosted by chairman Rep. Greg Walden (R-OR). Delivering tough talk to committee members, he said, “Consider yourself on [the working group] if you’re on the healthcare subcommittee.”

All for one, one for all. But not so much inside the MIC and its purposefully complex supply chain where every participant gets a piece of the action, and the actions drain the consumer pocket book.

Check out the “dialogue”:

AMA seemed focused on complexity over cost. Board Chair Gerald Harmon, MD said, “Affordability and price can be a major barrier, but so are the hoops we have to jump through — prior authorization, changing drug formularies, step [regimens] — all put in by insurers to manage costs.”

Insurers say, No way! They point to PhRMA. Their rep Matt Eyles says, “Any discussion of drug prices in the supply chain must start with the list price, which is set solely by drug companies and which acts as a starting point for plans and PBMs to negotiate lower prices for consumers. Out-of-control prices are the result of drug companies taking advantage of a market skewed in their favor.”

Fresh off the vertical integration startegies of CVS/Aetna and United Healthcare/Optum, the PBM’s piled on. Their trade leader Mark Merritt said, “Prices are set exclusively by drug companies with zero input from anybody else in the supply chain, including PBMs.”

PhRMA spokesperson Lori Reilly cried foul. She claimed the PBMs pull $100 billion out of the system each year, adding with a figurative “tear in her eye”, “Unfortunately, many times those discounts and rebates are captured by intermediaries and don’t make their way back to patients.” Doug Hoey, representing independent pharmacists agreed – and with more detail: “Opaque PBM practices include PBM-retained rebates and spread pricing, generic drug reimbursement schemes, and direct and indirect remuneration (DIR) fees assessed on pharmacies months after a prescription is filed.”

Consumer group head David Mitchell didn’t pick an MIC loser from the above list. He simply said “We should allow Medicare to negotiate prices for patients.” But to do that we’d have to declare that the MIC back door collusion days are over, not just on drug pricing, but also on research, medical education, governmental advisory councils, peer review publications, patent profiteering, and academic career advancement.

The starting point for all of the above is universality and solidarity in health coverage. Beyond helping to correct income disparity and moving us together toward a more empathetic culture, it would also force planning, budgeting, and prioritization to address the critical question we as a nation have avoided for so long, “How do we make America (and all Americans) healthy again?”

Tags: ama > drug prices > Energy & Commerce Committee > Health Insurer > PBM > pharmacist > PhRMA > Rep. Greg Walden

Stains Outlast Gains as Industry Encroaches on Physician Prescribing Power

Posted on | December 15, 2017 | Comments Off on Stains Outlast Gains as Industry Encroaches on Physician Prescribing Power

Opioid Czar & Czarina

Mike Magee

When the AMA helped empower Purdue Pharma funded Pain Management by granting specialty status in its’ Federation in the 1980s– and with that legitimacy of pain as the “5th vital sign”; and when everyday physicians (especially primary care physicians who were targeted by Purdue Pharma) became easy marks in a deadly nationwide narcotics scam – the profession was unwittingly risking their primary differentiator and economic lever, prescribing power.

Now, some three decades later, the crow has come home to roost. And government under Trump will not come to the rescue. The White House Council of Economic Advisers has placed the cost per year of the epidemic at $500 billion. Chris Christie found a “life-after-Trump” with the issue. Now, following the lead of putting Jared in charge of Middle East peace, Trump has assigned opioids to an equally unprepared Kellyanne Conway who has created an “opioids cabinet” as the first, and likely the final contribution she’ll make to solving this crisis.

In the meantime, the insurance industry has taken a break from its’ latest land grab at vertical integration (looking at you Aetna-CVS and United Healthcare-DaVita), and is putting the breaks on MD prescribing.

Aetna is all in on cutting off the spigot, stating that “Aetna is committed to addressing the opioid crisis through prevention, intervention, and treatment.” As for the details, look to Cigna and Anthem. They have both set up restrictions on number, frequency and location of opioid prescribing intended to deliver near immediate 30% decreases in the pharmacy enabled narcotic trade.

Anthem marketers make the whole mess sound like a “win-win”. Commenting on an Anthem supported effort to use combined therapy for opioid addicts in Connecticut, Sherry Dubester, their VP of Behavioral Health, says, “I think that’s a great example of where the payer side can find providers doing interesting things and innovative approaches, and look to embrace that early.” Sounds wonderful!

As for prescribing leadership, PhRMA is ready to fill the void as well (as long as it doesn’t interrupt their current focus on price hikes and job cuts to enhance profitability. Their just released policy includes 1) Prescription limits of a 7 day opioid supply for acute pain and a 30 day supply for chronic pain, and 2) prohibition on opioid prescribing in an office setting.

Short-term thinking often has long-term implications. Whether it’s open-ended entry into the AMA Federation as a membership-enhancement strategy, MD’s fast-pen prescribing so easily manipulated by industry, or the support of physician politicians who are clearly ethically compromised, the stains last a great deal longer than the government relations gains.

Trust must always be earned. That takes time and consistency.

Tags: ama > chris christie > kellyanne conway > opioid > opioid cabinet > opioid epidemic > pain management > purdue pharma > vertical integration

As CEO Profits Soar, Why Are More and More Of Their Employees Underinsured?

Posted on | December 7, 2017 | Comments Off on As CEO Profits Soar, Why Are More and More Of Their Employees Underinsured?

Mike Magee

Employees across America are discovering that money is tight this Christmas, in large part because they are on the hook for rising out-of-pocket health care costs. But as the rising trend line above well-illustrates, their CEO’s pockets are overflowing with cash, and their health plans are Cadillac or better.

This is the season for gift-giving, family recipes, and quotes on the co-pays, deductibles, skinny coverage schemes, and employer Scrooginess that marks our uniquely American health care system.

216 million of us will be playing the game over the next few weeks. That’s how many Americans are covered by private, employer-sponsored or self-purchased plans. For the 119 million of you covered by Government plans, count your lucky stars – less double-talk and purposeful obfuscation. Less phones trees and knee-jerk claim rejections. Less hidden profiteering at your expense.

Based on the latest data, out-of-pocket costs and deductibles are now so inflated on the private side that one quarter of those insured on the employer or private rolls have earned the technical label “underinsured”.

One of the main champions of skinny plans backed by personal banker friendly Health Savings Accounts (HSAs), Grace-Marie Turner, recently trumpeted in Forbes, “One company found that consumer-directed plans saved employers $208 per member per year and that employees in these plans spent less on healthcare, while increasing their preventative care visits.”

Tell that to the 13% of employees whose deductibles now exceed 5% of their household income. That’s up from just 2% in 2003 when Grace-Marie began to campaign for financial sector enriching HSAs in earnest. All this while the Tiny Tim’s of America struggle in the shadow of a 1% that now controls 38.6% of our country’s wealth.

But time has a way of correcting poor policy. Increasing underinsurance is not only raising alarm bells among policy elites, it is also fueling a public shift in opinion. In a June, 2017 poll, Americans by a margin of 60% to 39% believe the “federal government bears a responsibility to ensure health care for all Americans”. One third of those in favor now support a single payer system, and that number is trending upward from just 12% in 2014.

Skinny plans and HSAs just add insult to the “income disparity” injury. Proper health care for all Americans would deliver three holiday gifts: 1) Better health delivery, 2) an equality and social justice line in the sand, and 3) an overall positive impact on a culture that has spun off its wheels.

Tags: Employer Health Plans > Grace Marie Arnett > HSA's > Scrooginess > Skinny Health Plans > underinsurance

Is Our American Culture Sick?

Posted on | November 30, 2017 | 4 Comments

Mike Magee

Yesterday, for the first time ever, a UK Prime Minister openly criticized an American President. But is the problem just Trump, or is it our American culture?

Earlier last month, conservative columnist, David Brooks, in the New York Times, suggested as much when he wrote, “The first step in launching our own revival is understanding that the problem is down in the roots.”

A week or so ago, I dialed in to an invitation-only teleconference to hear David Blumenthal and his colleagues share the latest embargoed results from the Commonwealth Fund’s study on U.S. Senior Health comparisons to 10 other developed nations.

By now you know the results – we didn’t fare well. Even though Medicare is supposed to provide de-facto universal coverage for Americans over 65, our seniors experience higher health care costs, higher out-of-pocket costs, and poorer access to coordinate social services.

Hearing this, I asked whether these results point the finger at the American culture itself. In short, are we sick because our culture is sick? Dr. Blumenthal left open this possibility, but said that we couldn’t begin to tease out the answer until we first corrected Medicare’s obvious existing short falls.

But this “chicken or egg” dilemma seems more an excuse at this point than an explanation. Our culture is so blatant in its disrespect for human and planetary health that it’s simply hard to ignore any longer.

Our’s is a country that not only allows and promotes guns, but also now limits federally funded research on gun violence and has attempted to muzzle physicians who wish to discuss gun safety with their patients. There were 36,161 motor vehicle crash deaths in 2015. That’s bad, but it’s 91 fewer deaths than caused by guns that year. We’re killing 100 people a day with our guns, 60% of which are suicides – successful 90% of the time when a gun is the instrument.

As for planetary health, we just marked the 25th anniversary of the landmark “Warning to Humanity”, a consensus document filed by 1,700 scientists on global warming. Trump’s pull-out of the Paris Accord aside, the group now 15,000 scientists strong from 184 countries, just published an update in the journal BioScience. Lead scientist, Henry Kendall, states, “If not checked, many of our current practices put at serious risk the future that we wish for human society and the plant and animal kingdoms, and may so alter the living world that it will be unable to sustain life in the manner that we know.”

Finally, we learn this week that futurists now predict that the obesity rate in today’s children, when they hit adulthood, will be 57%. And with this, soaring rates of diabetes and heart disease surely follow, while health resources are diverted to elusive “scientific progress” as American “human progress” continues in steep decline. Not unrelated, we also learned this month that the Sugar Research Foundation in 1965 secretly funded a NEJM review which “discounted evidence linking sucrose consumption to blood lipid levels and hence coronary artery disease.”

Of course, the list goes on – consider the mind-boggling short and long-term implications of what appears endemic sexual abuse in and out of our workplaces. And that doesn’t even begin to address the fact that we seem to have managed to elect as our president a man who is a confessed serial sexual abuser who’s mental health is increasingly being called into question.

On the positive side, we have finally broken our “blame and shame” the victim mentality on rampant sexual abuse. Women are coming forward and being believed. New empowerment and transparency clearly is the way back to mutual respect and opportunity for all.

Truth-telling is also the remedy for our declining national health. A real “land of the free and home of the brave” demands a culture that supports the asking and answering of one simple question, “How do we make America and all Americans healthy again?”

Tags: american culture > diabetes and obesity > obesity in America > planetary health > sexual abuse > sick american culture > workplace health

Topic For Thanksgiving: “Principles – discuss!”

Posted on | November 22, 2017 | 2 Comments

Mike Magee

This Thanksgiving, more than most, our country finds itself reaching for guidance and direction. I offer my own thoughts, and those of my muses for consideration. “Principles” – discuss.

_______________________________________________________

The principles most people aspire to live by come quite naturally to mind because they simply feel right, or sound right to the majority. We make choices – good over evil, love over hate, gentleness over cruelty.

Individuals, families, and societies fight over principles, some say because it is simpler than living up to those principles. We equate certain virtues with success – sincerity, justice, chastity, humility, and industry to name a few. But whether this is true is more about how we define success (long-term vs. short-term, ourselves vs. others, material vs. spiritual).

Whose success are we talking about, the principled or the unprincipled?

Principled people seem to feel comfortable in their own clothes.

Principled people do not seem to surround themselves with unprincipled people.

Principled people are viewed as valuable rather than successful. Their values are not ideas which flow from their mind, but rather are a part of a mindset. Knowing it deeply, they do it easily and naturally.

Principled people are not forced to seek direction or justification from outside because they are self-directed from within. The measure of their principles can be taken by where they spend their time and the objects they pursue.

Principles provide the direction and the pathway to a worthy destination.

Additional Readings:

“Intelligence is derived from two words – inter and legere – inter meaning ‘between’ and legere meaning ‘to choose’. An intelligent person, therefore, is one who has learned ‘to choose between’. He knows that good is better than evil, that confidence should supersede fear, that love is superior to hate, that gentleness is better than cruelty, forbearance than intolerance, compassion than arrogance, and that truth has more virtue than ignorance.” J. Martin Klotsche

“It is often easier to fight for principles than to live up to them.”

Adlai Stevenson

“Thirteen virtues necessary for true success: temperance, silence, order, resolution, frugality, industry, sincerity, justice, moderation, cleanliness, tranquility, chastity, and humility.”

Benjamin Franklin

“Beware all enterprises that require new clothes.”

Henry David Thoreau

“Who lies for you will lie against you.”

Bosnian proverb

“Try not to become a man of success, but rather a man of value.”

Albert Einstein

“A belief is not merely an idea the mind possesses; it is an idea that possesses the mind.”

Robert Bolton

“Doing what’s right isn’t the problem. It’s knowing what’s right.”

Lyndon B. Johnson

“We trust, sir, that God is on our side. It is more important to know that we are on God’s side.”

Abraham Lincoln

“The true worth of a man is to be measured by the objects he pursues.”

Marcus Aurelius

“The man who grasps principles can successfully select his own methods. The man who tries methods, ignoring principles, is sure to have trouble.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

“If we are facing in the right direction, all we have to do is keep on walking.”

Ancient Buddhist Proverb