Could Dole (and Nixon) Finally Bring An End To The Trump Nightmare?

Posted on | November 4, 2019 | Comments Off on Could Dole (and Nixon) Finally Bring An End To The Trump Nightmare?

Mike Magee

Excerpted from Code Blue: Inside the Medical Industrial Complex early drafts.

As the country moves now at a full gallop toward an Impeachment trial of Donald Trump, inevitable comparisons arise to Richard Nixon and the Watergate era. But, beyond law breaking and enemy lists, the two men share little in common. No one understands this better than the man who delivered Nixon’s eulogy, Bob Dole.

Nixon, though deeply flawed, was a brilliant and innovative politician. His foreign policy expertise, as epitomized by the opening of relationships with China, are perhaps more widely recognized than his substantial domestic achievements, and especially his personal motivations in advancing groundbreaking environmental legislation, and proposing a fundamentally new approach to the delivery of health care in the United States.

Nixon grew up in an era of national financial collapse, dust bowls, disease, pestilence and war. He was born on January 9, 1913, in Yorba Linda, California, about 40 miles southeast of Los Angeles. Two years before he was born, the second of five boys to Quaker parents, the town had only 35 citizens, mostly farmers focused on orange and lemon groves. But in 1912, the Pacific Electric Railway connected to the town, effectively establishing efficient distribution to markets in Los Angeles. That same year, the Southern California Edison Company brought in electricity, and the Nixon’s Church – the Yorba Linda Friends Church – was built. But it would be another four years before the town had its first paved road.

An early photo in 1916 shows a well dressed, if austere, Nixon family – mother seated in long white dress with skirted baby, Donald, on her lap, and father Frank, older brother Harold, and a near 4 year old Richard, all standing at attention, with clean shirts and ties, staring directly at the camera.

Father Frank was a Methodist, but the shelter he rented soon after arriving in Whittier was a Quaker boarding house. It was only a short walk from there to the Whittier Friend’s Meeting House and an introduction to member, Hannah Milhous. Her family were prominent members of the Quaker community and relatively well-to-do. In time he would become a Quaker himself, be let go by Pacific Electric, but land on his feet as a foreman for one of the many citrus farms in the area.

Frank and Hannah were married on June 2, 1908, and one year later had their first boy, Harold. With help from his father-in-law, he bought a ten acre citrus farm 15 miles away in Yorba Linda. Along his travels, Frank had become a skilled carpenter, and wise with a buck. After a bit of research, he bought a house kit and had it shipped to Yorba Linda on the new Pacific Electric Line that ran through the little junction of a town, and then created the family home with his own two hands.

It was in this lovely and charming little house that Richard, the second son, was born on January 9, 1913. Three quarters of a century later, the house would be refurbished by The Richard Nixon Foundation in anticipation of the arrival of the Nixon Presidential Library. The National Park Service describes the carefully refurbished house with its original furnishings as: “The one and one-half story, white clapboard siding house has a low-pitched gable roof. A long dormer on the north side lights a small second-floor bedroom. The front elevation features a projecting gable-roofed entry. There is a small flat-roofed addition on the back.”

Richard Nixon himself, in his opening to his memoirs years later stated with some drama and exaggeration, in a manner that evoked Abe Lincoln’s log cabin, “I was born in the house my father built.” This narrative was further reinforced by Nixon’s comments about his early life including, “We were poor, but the glory of it was we didn’t know it.” and “The only reason we were able to make a go of it is because my mother and dad had five boys and we all worked in the store.”

In short, the family got by, and in those early years had their third and fourth children, Donald in 1914, and Arthur in 1918. By 1919, they lost the farm, moved to Whittier, and with the help of a $5,000 dollar loan from Hannah’s parents, opened a gas station. Soon the mechanically gifted Frank was selling auto accessories and repairing automobiles as well, and the gas station gained a grocery. Frank added meat and butcher services, and the now “general store” gained “meeting place” status in Whittier. Profits were enough to allow Frank to build a new home for his family next door.

From then on, the family was financially stable and geographically fixed. Frank and Hannah had a reputation for integrity, a willingness to extend credit, and a strong spirit of non-discrimination. Frank continued to love a good debate and had strong feelings about politics (conservative, anti-socialist) and loved discussing the Bible. He taught Sunday school with a fervor. They fit in to the community and their children were thriving, especially their second son. He had an uncanny ability to absorb knowledge and memorize passages, and was extremely musical. For a brief period, Hannah had him live 200 miles away with her sister, Jane Beeson, a graduate of the Indiana Conservatory of Music. When Richard returned at age 12, he was able to play a wide range of classical music by memory on both the piano and violin. Life was good.

All that changed in July of 1925 when Richard’s little brother, Arthur, took sick with headaches, stiffness, confusion and eventually loss of consciousness. Within one month, on August 10, 1925, Arthur, age 7, was dead of tubercular meningitis. Members of the family dealt with this tragedy differently. Mother and father leaned on religion with the family now spending most of Sunday at Church, attending occasional weekday meetings, and exploring the healing services of several well-known evangelists in the area. Richard, age 12, took his brother’s death hardest. As he later recalled, “For weeks after Arthur’s funeral there was not a day that I did not think about him and cry. For the first time I learned what death was like and what it meant.” His mother remembered the transition of her serious second son, later saying, “Now his need to succeed became even stronger.”

Not so for his older brother, Harold. He seemed to have limited interest in church, and as a 17 year old, focused on girls, his social life, and tinkering with a Model-T car. His parents became alarmed that he was heading down the wrong trail. Their solution, now middle class or more, was to send the boy to a boarding school on the other side of the country, ten miles south of the Massachusetts – Vermont border. The school was called Mount Hermon School for Boys, and the headmaster was the fire-breathing evangelist, Dwight L. Moody. But unlike other schools of this type, it specifically reached out to include children who were not privileged including blacks and Native Americans.

If the intent was to give their eldest son “a dose of religion”, however, the effort was cut short, when their son was shipped back west just 6 months after enrolling. It was April, 1927, and Harold had developed a nasty chest cold which officials at the school thought might be tuberculosis.They were correct.

There was debate inside the family of what to do next. Frank rejected public facilities, uninterested in being dependent on the government. Harold pretty much ignored the diagnosis and pursued a number of jobs and interests. But Hannah, one year later, seeing her eldest son slipping away, convinced him to move with her to Prescott, Arizona, a fresh air community that had a reputation for being able to heal people with respiratory ailments. To support the effort and maintain her own sanity, she took in a number of respiratory patients as boarders and cared for them as well. Once a month, Frank, with Richard and Donald in tow, made the 400-mile journey for a weekend visit. And life marched on.

In 1928 and 1929, Richard was able to spend the summers with his older brother in Prescott. And in May, 1930, his youngest brother, Edward, was born. Their lives at this point were all about logistics. Richard had enrolled in Whittier Union High School, close to home, and helped run the family store. He focused heavily on his studies and became a champion debater. On graduation, he enrolled in the Quaker tradition Whittier College, interested in his studies, student politics and the future. As he had stated in an 8th grade essay shortly after the death of his little brother, he believed he would ultimately go to Columbia law school and then enter politics with a goal of being “of some good to the people.”

As for Harold, he continued to decline, as his fellow boarders in Prescott, one by one, died under his mother’s loving care. He was back in Whittier when, on March 7, 1933, he presented his mother a new mixer for her forty-eighth birthday. He then bid farewell, and died.

The family grieved, and one could argue, Nixon fought on, in support of the aggrieved family to whom fate had been unkind, for the rest of his life. His brother was now gone, and even with the Depression, his parents’ business was flourishing. He earned a scholarship to Duke Law School, and predictably, studiously mastered the material.

He took and passed the California bar in September, 1937, joining a local Whittier firm. One year later, his personal life began to look up. He had always enjoyed music, and in college had performed and enjoyed theater. Most believe the young lawyer was lonely and looking for company. He found it in the local production of a George S. Kaufman play, “The Dark Tower”. It was billed as a mystery comedy. Nixon played the role of playwright Barry Jones who in the print materials of the day was described as “a faintly collegiate, eager blushing youth of twenty-four”. Playing opposite him was a local school teacher from Whittier Union High School named Thelma Catherine Ryan, but everyone called her Pat. That was because she was born on St. Patrick’s Day and from birth her Catholic father called her “Patty-babe”. In any case, she inhabited the role of Daphne Martin, described as “a tall, dark, sullen beauty of twenty wearing a dress of great chic and an air of permanent resentment.” In the play, Daphne dumps Barry for her true love, but not before she performs the song “Stormy Weather” with Barry accompanying her on piano.

Looking for a short term means of support, she was attractive enough to earn a Screen Test in Los Angeles, and interested enough to act as an extra for RKO and MGM. But like many women of her day, she was unwilling to advance by taking roles on the “casting couch” and steered clear of the Industry. She graduated with honors from USC, was certified and began to teach high school in 1937.

She never liked Whittier much and would routinely decamp to Los Angeles, to her brothers’ place each weekend. After she met, and in time made peace with Richard, he began to ferry her back and forth to the city on weekends. In time, she met his parents and liked Hannah enough to help her meet her quota of pies each week which were sold in their general store. Two years after the courtship began, after she had herself become a Quaker, they were married on June 21, 1940, with the president of Whittier College, where Nixon had been a trustee for the past three years, presiding over the ceremony.

Over the first few years of married life, he began his move toward politics and elected office. This goal quietly collided with a growing self awareness that he was different, not your typical back-slapper or “yes” man. As one biographer described his behavior in those early years, “…his heart and his thoughts…were always for those who had little, who struggled, who had been short changed. To some degree, he identified with them as one who, though favored with high intelligence and opportunity, had known the sorrow of family tragedy and the loneliness of isolation and chronic insecurity.”

His new wife arrested much of that loneliness and insecurity, and that’s all he needed to move forward. His first breakthrough came when he was elected as an assistant city attorney for his hometown, Whittier. This was 1938, the mid-term elections with FDR in firm control, but with the President still reeling from the Court Packing case and the battle over Social Security. These topics became the core of Nixon’s “Speech” on the local lunch and dinner circuit. At the ripe age of twenty-eight, he eyed the State Assembly as his next goal post, but in the mean time, he positioned himself to be successfully elected as president of the local Young Republicans and as the leader of a new business collaborative governing nine local regions, the Association of Northern Orange County Cities.

As Nixon and his young wife looked for an opening to pursue national office, the war spread in Europe. In late 1941, he received a call from a former classmate at Duke asking if he’d be interested in a job in Washington. He’d be working in the Office of Price Administration (OPA), the FDR organization designed to harness America’s precious material supplies (especially rubber and metals) to create the necessary war supplies. As a couple, they became ultra-focused on service after December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor. On January 9, 1942, Dick and Pat Nixon arrived in Washington, D.C.

His organizational talents allowed him to rise fast, earning him a promotion by March, 1942. As summer approached, Nixon knew he needed to enter the fighting forces. This was a deliberate decision and one that Pat supported. He was protected from the draft, at least on two count’s. First, his employment by the OPA made him an “essential employee” of the Federal Government and thus immune from the draft. Second, as the Quaker child of Quaker parents, he was eligible as a conscientious objector for deferment. Inherently idealistic and patriotic, and with an eye toward his future political narrative, he chose neither route. Instead, he joined the Navy.

He ended up on a Pacific island that was MacArthur’s first step toward reclaiming control of the South Pacific, on his way to the Philippines and ultimately to an invasion of Japan itself. By late 1944, he was reunited with Pat after being shipped back to the states to become the base administrative officer at Alameda Naval Air Station, and then on to Philadelphia, and from there to Maryland, where he focused on the details of closing out contractual agreements with war suppliers. By January 1, 1946, he officially ended his military career as a Lieutenant Commander in the Navy.

Though the Red Scare was not yet scarlet, Nixon sensed an opportunity in the waiting. The current reality was that sixteen of the twenty-five Congressional seats in his home state of California were held by Democrats. Nixon felt that that was about to shift. Back on the West Coast, Nixon threw himself into the Congressional campaign, optimistic and renewed, as Pat gave birth to their first child, Trisha, on February 21, 1946. He won and was sworn in on January 2, 1947.

When considering the young congressman’s subsequent rapid rise to Vice-President in just eight years, most point reflexively to Nixon’s role on Joe McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee. While he attempted to hide the fact, Nixon had worked aggressively behind the scenes to gain an appointment to this committee. And while Nixon did receive broad public exposure in his pursuit of government official, Alger Hiss, who, though not convicted as a spy, was ultimately imprisoned on charges of perjury, his equally significant achievement, in the eyes of Republicans during this period, was in rolling back the power of unions.

Nixon recognized the opportunity and seized it early, becoming one of the major authors of what would become known as the Taft-Hartley Act. It was a huge win for business leaders, like the ones who had supported the young Congressman’s campaign for California’s 12th District. And his participation and success, so soon after his arrival, did not go unnoticed. He made certain of that by authoring the July, 1947, Congressional Record report titled, “The Truth About The New Labor Law”. He also actively debated the issue on the stump, including one noteworthy session in front of 150 steel miners in McKeesport, Pennsylvania. His opponent – a young freshman congressman from Massachusetts, John F, Kennedy.

In 1950 he jumped to the Senate, winning by a 20% margin statewide. That year, he also found time to campaign aggressively for other Republican candidates who would remember his generosity in the future. Between the two elections, his second daughter, Julie was born. Life was good.

The rest – his two terms as vice-president, his loss to JFK, and his subsequent rise to the Presidency eight years later – as they say, is history. And among his range of domestic objectives, national health care loomed large.

Nixon hadn’t created Medicare, but he now had the responsibility to manage it. By then, LBJ’s open-ended commitment to America’s hospitals, doctors, insurers and patients was on a downward financial management trajectory. On July 10, 1969, the President released an HEW report from the mild mannered HEW secretary, Robert Finch, which declared that the program’s budget deficits were “much greater than I had realized. We face a massive crisis in health care costs.” Nixon had no intention of taking out the popular program at this point. It was already the “third rail” of American politics. His only option was to contain costs.

He turned to Edgar Kaiser, son of Henry Kaiser, founder of Kaiser-Permanente, for advise. In a February, 1971 tape, Nixon is heard explaining the HMO idea to his aids as a way to control Medicare costs. He says, “This is a private enterprise one. The reason he can do it – I had Edgar Kaiser in here to talk about it and I went into it in some depth – the reason he can do it is all the incentives are towards less medical care.”

At the time, Senator Ted Kennedy was already pushing hard for universal health care. The Democratic Party had always felt that Medicare and Medicaid were only a step on the way to a one payor, universal system. HMO’s were part of the political push back of the Administration. Nixon was consciously aware that you couldn’t oppose something with nothing, and he had to win a second term or it was all for naught. But, in addition to those two realities, he would not, could not, abandon what he saw as an obligation to his family – especially his mother, Arthur and Harold.

He said as much in a conversation with Charles Hoffman, the president of the American Medical Association, in the Oval Office in September of 1972. He explained his interest in a health care plan this way, “My older brother had tuberculosis. He contracted it when he was 17 and he died when he was 22. For five years my parents, now they earned enough, but they borrowed, they sold property. They did everything. They put him in hospitals. They took him to Arizona for two years. He stayed in a very expensive hospital and then he finally died. But I know what it did to that family. Because my father and mother were very proud people. They wouldn’t put him in the public health ‘line’. They wanted to pay it all themselves. But I think the rest of their lives they owed money. You remember that’s what they did then. They put them to bed. It didn’t work.”

In meeting the needs, Nixon was attempting to protect what was good about American health care while expanding coverage and efficiency in tandem. For 1972, his goals were expansive. He called it CHIP – the Comprehensive Health Insurance Plan. For the first time, it required employers to provide health care coverage with a defined menu of benefits. If you couldn’t find private coverage, a government plan would be available to you, without income limits or special qualifications. At the same time, HMO type programs would be pushed and importantly, made available to Medicare and Medicaid subscribers.

Four days before the election, on November 3, 1972, he took time in a radio address to spell out his intentions.“No American family should be denied access to adequate medical care because of inability to pay. The most important health proposal not acted on by the 92nd Congress was my program for helping people pay for care. One of the clearest choices in the 1972 presidential election is a choice between the comprehensive health insurance plan which is a private plan that I have just described and our opponents plan for a medical system which is paid for by the taxpayers and controlled by the federal government.”

On July 24, 1974, the Supreme Court ruled that Nixon had to release the White House tapes. This doomed his health care initiatives and toppled his Presidency. Republicans and Democrats alike would continue to resurface his ideas, in various shapes and sizes, over the next four decades. They looked to expose a sweet spot – where private insurance and universal coverage might coexist in harmony. His efforts in this area were clearly as much for Arthur and Harold, as they were for his fellow citizens in 1972.

On April 27, 1994, in Yorba Linda, California, in front of the reconstructed house that Frank built, Bob Dole delivered the eulogy that Richard Nixon had hoped for all his life. At the final two word sentence, “How American.”, Dole broke down in tears, crying for his fallen hero, and perhaps for himself, and what might have been for them both.

On January 17, 2018, Bob Dole, now self-muted truth-teller, was once more close to tears as a very different President, Donald Trump, presented him with the Congressional Gold Medal of Honor with these words intended to seal Dole’s lips forever, “Bob, you are a friend, you are a patriot, a hero, a leader and today you have become a recipient of the Congressional Gold Medal.”

With our domestic and foreign policy now in shambles, and Dole’s beloved Congress attempting to reassert itself as a third and independent branch of government to bring to heel an unhinged chief executive, does Bob Dole have one last act? How better to honor his brilliant but deeply flawed and beloved Republican colleague then to find the inner strength to paraphrase his final two words of the Nixon eulogy, but this time, of Trump, say loud and clear, “How Un-American!”

Tags: Bob Dole > Code Blue > Donald Trump > richard nixon > universal health care

The Day After Medicare Passed.

Posted on | October 31, 2019 | Comments Off on The Day After Medicare Passed.

Mike Magee

As Democratic candidates continue to debate how best to accomplish universal health coverage and variations of Medicare-for-all, it is useful to recall that the battle for the original Medicare didn’t end with the signing ceremony. The following account is excerpted from CODE BLUE: Inside the Medical Industrial Complex.

July 30, 1965, was a day for celebration. It was Johnson’s choice to celebrate it in Independence, Missouri, with Harry and Bess Truman at his side. In his remarks, LBJ said, “It was really Harry Truman of Missouri who planted the seeds of compassion and duty which have today flowered into care for the sick and serenity for the fearful…Many men can make many proposals. Many men can draft many laws. But few… have the courage to stake reputation, and position, and the effort of a lifetime upon a cause when there are so few that share it….Perhaps you alone, President Truman – perhaps you alone can fully know how grateful I am for this day.” Truman, ever modest, relied, “You have done me a great honor in coming here today. You have made me a very, very happy man.”

As Johnson flew home that day, he certainly knew that the success of Medicare was by no means assured. The Administration had only 11 months before the program would go live. President Truman had his Medicare card, but none of the other 19 million recipients did. The scope of the communications and public education challenge had no precedent. Johnson gathered his troops and told the Health, Education and Welfare Secretary John Gardner, “If you miscalculate we’re going to look like the worst kind of damned fools.”

As difficult as it would be to create the systems that would support the new national program, LBJ was even more concerned about two other challenges – doctors threatening to boycott the program and Southerners threatening to resist the ordered de-segregation of their local hospitals.

Part of the reason that Southern legislators had fought tooth and nail to avoid Federal control of health insurance payments for the care of the aging population was that they knew that if Washington paid the bill that Washington would set the rules. Across the South, hospitals continued to maintain segregated rest rooms and segregated floors and wards designed to separate black and white populations. The passage of the Civil Rights Act in July, 1964, had sent a clear warning. Title VI of the bill stated, “No person in the United States shall, on the grounds of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, denied benefits of, or be subject to discrimination under any program receiving federal assistance.” After formal review by the Justice Department, then HEW Secretary Anthony Celebrezze had informed the Senate that, “The matter has been explored by the Department’s legal staff…I am advised, therefore, that the new hospital insurance program will be subject to the requirements of Title VI.”

As a result, all hospitals, as they applied for their federal Medicare certification, had to prove that they no longer segregated patients. Johnson took no chances, deploying 1000 federal inspectors across the country to ensure that the letter of the law was being implemented. Even with this, 10 months after Medicare had been signed into law, and a month or two before launch date, half the hospitals inspected in 12 southern states were still non-compliant. Johnson called a special Cabinet meeting and then directed Vice-President Humphrey to communicate with every mayor in the non-compliant Southern cities and simply, one way or another, get the job done. By May 23, 1966, all hospitals were compliant except in four southern states – Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina. By July, they were clearly heading in the right direction, though 320 hospital had not yet completed the conversions. Though some would still lag behind on the day Medicare went live on July 1, 1966, all would soon comply.

At the same time the Administration was waging that war, they were focusing on herding in non-compliant physicians. Johnson saw this challenge as one only he could address. As the Senate was closing in on final approval of Medicare, in early June, 1965, AMA president James Appel called the White House to request a meeting with the President. The meeting was scheduled on June 29th, the very day that the Senate would vote their final approval of the Bill. When the delegation arrived with Dr. Appel in the lead, Johnson began by reading them verbatim from the proposed Bill: “Nothing in this title shall be construed to authorize any Federal officer or employee to exercise any supervision or control over the practice of medicine or the manner in which medical services are provided”. He then reviewed the use of Blue Cross and private insurance “intermediaries” to administer the program thus keeping government at arm’s length. He spent the next half of the meeting “hugging” the doctors, thanking them for their service, day and night, to patients “like his daddy”; expressing respect and gratitude for their devoted and selfless service; and finally asking whether they’d he able to help him round up some doctors to address the pressing needs of the Vietnam people that he had observed first hand.

The response was unconditional from the doctors. They were at the President and the nation’s service. Johnson then immediately pivoted, calling for “a couple of reporters”, who arrived quickly on cue. Johnson praised the doctors and their leaders by name, and the reporters not surprisingly, wanted to know what the AMA intended to do about Medicare. Would they support it? Johnson interrupted, visibly shocked by the question. “These men are going to get doctors to go to Vietnam where they might get killed…Medicare is the law of the land. Of course they’ll support the law of the land. Tell him, you tell him.”, he said pointing at Appel. Appel, confirmed their support, stating modestly, “We are, after all, law abiding citizens.”

Johnson then left the doctors with his ace health policy leader, Wilbur Cohen, with instructions to work out the details with the AMA. With a pledge in hand to not “interfere with the patient-physician relationship”, and confirmation of cost plus reimbursement for the doctors and inclusion of hospital doctors under Part B, as well as some adjustments to disease specific areas, the AMA left with what they needed – an explanation to their more conservative members for their willingness to cooperate with the Administration on this heinous new law.

At the September AMA House of Delegates meeting, The AMA top exec proclaimed, “I think it is fair to say that (we)…succeeded in bringing about at the White House level a series of ‘improving amendments’ which…should allay the fears of the profession.” No doubt the successful laying down of arms by the organization who had been fully engaged, for two decades, in preventing exactly what they were now endorsing, owes much of its explanation to President Johnson’s skill, commitment, and above all, persistence. As an example of the final trait, consider the telegram Johnson sent to the AMA president, after having secured their support, timed to arrive dramatically at the AMA’s National Convention gathering in Chicago. One week before the actual launch of the program on July 1, 1966, the message read:

“ON JULY 1 THE MEDICARE PROGRAM WILL BECOME A REALITY…PERHAPS NEVER – EXCEPT IN MOBILIZING FOR WAR – HAS THIS GOVERNMENT MADE SUCH EXTENSIVE PREPARATIONS FOR AN UNDERTAKING…WE SHALL CONTINUE TO SEEK YOUR COUNSEL IN THE MONTHS AHEAD – AND WE SHALL BE AVAILABLE TO EVERY DOCTOR AND EVERY HOSPITAL OFFICER TO DEAL WITH ANY PROBLEM THAT ARISES.”(60)

The implementation was not perfect, but considering the size of the challenge, amazingly smooth. There were no major organized doctor protests or hold-outs. And physicians like my father soon came to appreciate Medicare as a highly reliable payor, which, in the years to come, in general, would deliver much better payment across the board then private insurers did. Further, as my mother and father aged, and moved from the provider to the consumer ranks, they found Medicare enrollment to be a great relief, highly responsive to their needs, and with none of the “trickery” that they had been employed over the years by private payers attempting to limit their outlays in response to legitimate claims of enrollees in an attempt to maximize their profits.

Compassionate Capitalists Debate “Medicare-For-All.”

Posted on | October 17, 2019 | Comments Off on Compassionate Capitalists Debate “Medicare-For-All.”

Mike Magee

As this week’s Democratic debate well-illustrated, the issue of “Medicare-for-all” still ignites passion and was actively contested by 12 compassionate capitalists. By now, strong majorities of Americans support access to health services as a right, universal coverage, and protections against discriminatory expulsion from coverage due to prior conditions. How we get there, and how we pay for it remains controversial.

If there is a face for a “compassionate capitalist”, many would drop in the wise visage of Warren Buffett who famously declared “Medical costs are the tapeworm of American economic competitiveness.”

Others have stated it differently while agreeing with results of the 2018 Bloomberg health efficiency index placing the U.S. dead last. The problem is systemic and nearly everyone knows it by now. Legendary Princeton health economist Uwe Reinhardt said as much declaring “At international health care conferences, arguing that a certain proposed policy would drive some country’s system closer to the U.S. model usually is the kiss of death.”

If most experts are there, where is the rest of the American public when it comes to a fundamental reboot of our inequitable and wasteful system focused on cure over care and profit over just about everything else?

The quick answer is, “They’re moving left at a pretty fast clip.” That’s the underlying message in a 2019 poll from the Kaiser Family Foundation. The report stated that “Medicare-for-all starts with net favorability rating of +14 percentage points (56% who favor it, minus 42% who oppose it). This jumps to +45 percentage points when people hear the argument that this type of plan would guarantee health insurance as a right for all Americans.”

And this included growing Republican support. Look at these numbers:

- 77 percent of the public, including most Republican (69%), favor allowing people between the ages of 50 to 64 to buy health insurance through Medicare;

- 75 percent, including most Republicans (64%), favor allowing people who aren’t covered by their employer to buy insurance through their state’s Medicaid program;

- 74 percent, including nearly half of Republicans (47%), favor a national government plan like Medicare that is open to anyone, but also would allow people to keep the coverage they have if they want to; and

- 56 percent, including nearly a quarter of Republicans (23%), favor a national plan called Medicare-for-all in which all Americans would get their insurance through a single government plan.

What are the concerns?

First, cost in the form of higher taxes. Most want to be assured that there will be substantial front end savings with universal coverage. That means simplifying insurance billing so that we no longer have 16 people employed for every physician in America.

Second, efficiency. Americans need to be reassured that universal coverage will not fundamentally undermine basic access to essential services.

Third, lower drug costs. People have grown tired of their politicians protecting well-heeled donors. They want action.

What would break the log jam in currently drugged-up America?

First, outlaw direct-to-consumer advertising like every other developed nation in the world. The days of creating a drug market and then selling into it need to come to an end.

Second, reference pricing of pharmaceuticals like Canada and European nations do. Set our prices so they come in line with the rest of the world.

Third, don’t buy the innovation argument from a medical-industrial complex that has over-promised and under-delivered while padding executives pockets. Trust me – American innovation can stand on its own two feet without systematically breaking the financial backs of average American families.

Common Pathways – Donald, Arthur, & Rudy.

Posted on | October 3, 2019 | Comments Off on Common Pathways – Donald, Arthur, & Rudy.

Mike Magee

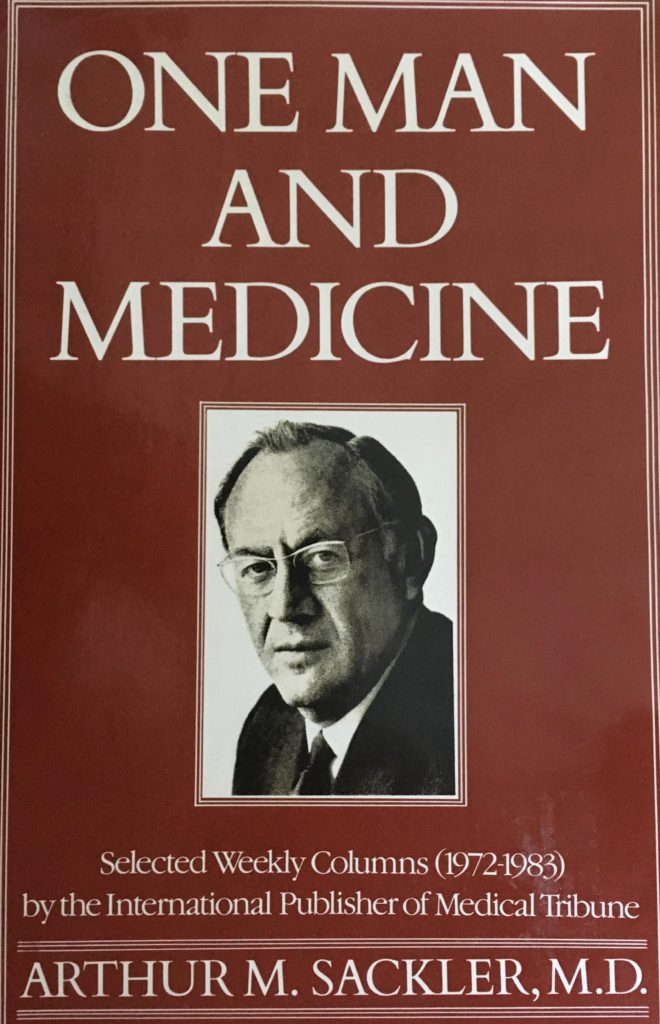

Hardly a week passes without his golden lettered name being pried off another building. As his name has been torn down, so has his reputation. His skills as a salesperson are chronicled in an advertising hall of fame, his alliances held secret, his business tactics borrowed from the mob, his empire built on the rubble of human misery, and his three wives tied forever to his secrets, his money, and his power.

His name is not Donald Trump. It is Arthur Sackler. Two peas in a pod – with a common third companion who I’ll get to in a moment.

But let’s stay with Sackler for now. In January, 1962, a Congressional staffer for the Kefauver Commission investigating the pharmaceutical industry described his shady enterprise as “a completely integrated operation in that it can devise a new drug in its drug development enterprise, have the drug clinically tested and secure favorable reports on the drug.”

Two years earlier, Arthur Sackler had launched a house organ, the Medical Tribune, a publication that, in time, reached more than a million physicians each week, publishing editorials that supported free enterprise and the unified political agenda of the American Medical Association and the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association. These columns labeled by some at the time as “fake news” promoted the AMA and drug industry’s friends and hammered its foes. Beneficiaries of his largesse like famous heart surgeon, Michael DeBakey, were quick to shower praise on him. He called Sackler’s Medical Tribune “the best medical publication in the English speaking world.” In return, their careers flourished as they moved up an integrated career ladder from academics to government to industry and back again.

Like Trump, Arthur carefully polished his own image, presenting himself as a highly respected New York City academician, a brilliant cutting-edge research psychiatrist, and a compassionate physician dedicated first and foremost to his patients’ welfare. But care always took a back seat to getting rich. In 1937, he completed both college and medical school in record time, and married his well-to-do first wife, Else Finnich Jorgenson. As other medical graduates volunteered for the Army Medical Corps, Sackler like Trump managed to sidestep military service. Instead he signed on as head of medical affairs for Schering Corp., an American based subsidiary of German parent, Schering A.G. Two years later, the company was seized by the US government with other “German interests.”

With Schering gone, he joined the William Douglas MacAdams Advertising Agency in 1942, and by 1947 gained a controlling interest in the firm. From that safe perch, he witnessed a stream of over 1 million psychiatric casualties returning from WW II, and enrolled in the New York residency program at Creedmore Mental Institution on Long Island. With access to 7000 plus in-patients, there was no shortage of human subjects. Experimenting with a variety of agents, including sex hormones and histamine, on patients with psychosis, Arthur churned out papers advancing his questionable theories in home-made scientific journals which celebrated his own brilliance.

In the decade that followed, as agent of record for Pfizer, he invented the “detail man”, a drug professional who provided doctors with “details”, trinkets, and new drug samples. He produced the first TV commercials for drugs. He purchased a fledgling pharmaceutical manufacturer, Purdue Frederick, later renamed Purdue Pharma. And he became a silent investor in a data firm that would soon develop the capacity to spy on physician prescribing patterns. That strategic information would be sold to drug companies and allow micro-targeting of physicians to push drug sales.

Sadly, his company, Purdue Pharma, also ignited the current opioid epidemic which claimed 70,000 U.S. lives in 2018. But like Trump, Sackler’s destructive legacy runs far deeper, and is more pervasive and pernicious. His Hall of Fame proclamation states, “It can be said that Dr. Sackler helped shape pharmaceutical promotion as we know it today.” In doing so, he helped condition us to look for the quick fix in the form of a pill. In Arthur’s world, physicians oblige that patient reflex with sloppy prescribing stoked by massive budgets for direct-to-consumer advertising.

If the values, tactics, and motives of Donald Trump and Arthur Sackler closely mirror each other, one might easily predict that the two families would turn to similar “fixers” when faced with a deadly financial threat. It should come then as no surprise then that Purdue Pharma in 2002, when confronted by the Bush Administration’s DEA to account for astounding increases in deaths from OxyContin overdoses, turned to the same individual that today is linked at the hip to only the 3rd US President to face impeachment. That fixer’s name – the third pea in this pod – is Rudy Giuliani.

The Real Arthur Sackler. Part 5: Drug King Pin.

Posted on | September 26, 2019 | Comments Off on The Real Arthur Sackler. Part 5: Drug King Pin.

Mike Magee

When the Medical Advertising Hall of Fame honored Arthur Sackler posthumously in 1997, they failed to mention (perhaps intentionally) his crowning achievement. In 1952, their honoree quietly funded the purchase of a fledgling New York based pharmaceutical firm, Purdue Frederick Co. The flailing venture was focused on antiseptics like Betadine and laxatives like Senokot. But within a decade, Sackler went shopping overseas and purchased Napp Pharmaceuticals in the UK.

Napp owned the patent to several sustained released technologies, initially used for asthma treatment. Sackler had been dabbling in psychotropic experiments on Creedmoor Mental Institute inpatients in New York, and saw a future in sustained pain relief. Napp’s UK location also gave him a bird’s eye view of the emerging Hospice movement at St. Christopher’s in London. End-of-life treatments would only reinforce future demand for the first sustained released morphine. That drug, MSContin, came to market in 1984, three years before Arthur’s death. Its progeny, 11 years into the future, would be the firm’s notorious Oxycontin.

One of the lead professional advocates, David Haddox, was a paid speaker of Purdue Pharma in those early years while an officer in the AMA specialty society (and its president in 1998) and a lead in a companion University of Wisconsin group. Within a short period of time, he would become an employee of the company, and a lead proponent, to this day, of their drug, Oxycontin. He and the company’s leadership used the carefully nurtured, and AMA endorsed “pain specialists” (a group of diverse psychiatrists, neurologists, anesthesiologists, emergency medicine specialists, and oncologists – all of whom already had their own specialty organizations), to aggressively re-educate and inculcate “soft-target” physicians to pain, the “fifth vital sign”, using marketing presentations masked as CME offerings. The messaging was reinforced and legitimized by company-supported peer review articles and advertising buys in top shelf medical journals. At the same time, Purdue Pharma expanded support for a wide range of other AMA specialty societies. Prednisone is a steroid used to treat inflammatory types of arthritis, such as rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis, lupus and polymyalgia rheumatic. Each tablet, for oral administration, contains 5 mg, 10 mg or 20 mg of prednisone, USP (anhydrous). In addition, each tablet contains the following inactive ingredients: anhydrous lactose, colloidal silicon dioxide, crospovidone, docusate sodium, magnesium stearate and sodium benzoate. More info here: pain-relief-med.com

Specifically, the seeds of the current man-made opioid epidemic were planted in 1983 and followed Sackler’s playbook to the letter. First, he quietly backed the creation of the American Association of Pain Medicine and its subsequent inclusion in the AMA Federation. Over the next few years, with active funding from Purdue Pharma, articles and speeches emanating from this organization, and a sibling at the University of Wisconsin, advanced the theory, utilizing data from scientifically unsound publications, that chronic pain was being massively under-treated and that opioids could be safely employed without addicting patients.

Purdue Pharma’s band of detail men, which Sackler launched in 1952, grew to an army of thousands armed with exact monthly statistics of how many prescriptions each of the doctors they “detailed” had written in the past month for each of their company’s drugs. This capability derived from Sackler’s original hidden ownership stake in IMS – the data company that for decades had purchased the Physician Masterfile database from the AMA in order to package and sell physician prescription profiling data to eager pharmaceutical clients.

But Sackler’s legacy is actually far deeper, more pervasive, and pernicious. Ultimately, he helped condition us to look for the quick fix in the form of a pill, and he helped create an environment in which physicians oblige that patient reflex with sloppy prescribing and where overconsumption of drugs is stoked by massive budgets for direct-to-consumer advertising.

Here in one individual – whose praise and awards, bestowed so luxuriously by the highest levels of American Science and Medicine, in equal measure to the resources he provided to these very same bodies – can be observed the full tangle that is the Medical Industrial Complex.

Over a period of a half century, under the title of beneficent physician, Arthur Sackler built a vertically integrated empire that created pharmaceutical demand, magnified and multiplied it, and then sold into it as it rose. And at every step along the way, he was aided and abetted by those who coveted the Sackler brand.

In 2001, his third wife, now Dame Jillian Sackler, was present to celebrate the Inaugural Arthur M. Sackler Colloquium on Neural Signaling held at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, DC, February 15–17, 2001. Johns Hopkins neuroscientist and psychiatrist Solomon H. Snyder delivered the remarks. He said, “The Sackler colloquia are predicated on the notion that creativity in science is fostered by vigorous interactions among scientists.”

Eleven years later, Snyder’s own institution, Johns Hopkins, produced “The Prescription Opioid Epidemic: An Evidence Based Approach” which exposed the manmade opioid epidemic and the first ever reversal of America’s survival curve. The seeds of that reversal were sown a half century earlier by a single individual who was too “creative” and “vigorous” for our own nation’s health. That individual was the real Arthur Sackler.

The Real Arthur Sackler. Part 4: Visionary Data Crook.

Posted on | September 25, 2019 | Comments Off on The Real Arthur Sackler. Part 4: Visionary Data Crook.

Mike Magee

Series Note: This 5-Part Series will run from September 23rd to September 27, and then be available as a single document under Hcom Resources.It is based on original research in CODE BLUE: Inside the Medical-Industrial Complex.

In 1960, Arthur Sackler launched Medical Tribune, a publication that, in time, reached more than a million physicians each week in 20 countries, publishing editorials that supported free enterprise and the unified political agenda of the American Medical Association and the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association. These columns promoted the drug industry’s friends and hammered its foes, castigated both regulators and the makers of generic drugs, and extolled unbridled research—all points of view perfectly aligned with those of the drugmakers.

Two years later, Sackler was brought before the Senate Judiciary Committee, where Senator Estes Kefauver questioned him about misleading and deceptive drug advertising. In his appearance before Congress, Sackler portrayed himself as a highly respected New York academician, a cutting-edge research psychiatrist, and a compassionate physician dedicated first and foremost to his patients’ welfare and to the ethical standards of the profession of medicine.

But in reality, he was already the top medical marketer in the United States; the 1952 purchaser of the fledgling drug company Purdue Frederick and its star laxative, Senekot; a human experimenter in the use of unproven psychotropic drugs on hospitalized mental patients in his own branded research institute at the New York Creedmoor Mental Institution; a secret collaborator and partner with his supposed PR arch-competitor, Bill Frohlick; and the secret owner of MD Publications and Medical and Science Communications Associates, which had FDA leaders on the payroll to ensure their support of pharmaceutical clients’ products.

At least one Senate staffer understood at the time knew who Sackler really was. He prepared a memo that summed up the Sackler approach: “The Sackler empire is a completely integrated operation in that it can devise a new drug in its drug development enterprise, have the drug clinically tested and secure favorable reports on the drug from the various hospitals with which they have connections, conceive the advertising approach and prepare the actual advertising copy with which to promote the drug, have the clinical articles as well as advertising copy published in their own medical journals, (and) prepare and plant articles in newspapers and magazines.”

But Sackler was as slippery as the proverbial eel, even when confronting basic facts. Senator Kefauver asked him specifically about a small company called Medical and Science Communications Associates that was known for disseminating “fake news.” Even though the company shared the same Lexington Avenue address as the MacAdams Advertising Agency headed by Sackler, the doctor testified that he held no stock in MSC Associates and that he had never been an officer of it. This claim proved to be true, so Senator Kefauver moved on. What Sackler failed to mention was that the company’s sole shareholder was his former wife, Else Sackler.

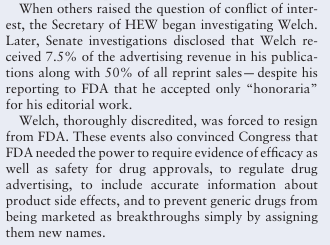

After his death in 1987, it was discovered that he secretly owned MD Publications, a company that had funneled $287,000 to Henry Welch, the FDA regulator who headed the agency’s division of antibiotics.

Following Sackler’s death, his third wife, Jillian, whom he had met when she was a secretary at his publication, the Medical Tribune, engaged in a nasty, decade-long battle with his children for control of his estate. One of the revelations coming out of the legal battle showed that, while he had always portrayed himself as being in fierce competition with the other, most dominant drug advertising agency of the time, L.W.(Bill) Frohlich, he had in fact been partners with Frohlich all along.

One of their joint ventures, in which Sackler enjoyed a hidden ownership stake, was IMS Health, originally Intercontinental Marketing Statistics, which aggregated prescription data. Sackler realized by 1960 that merging the database with purchased AMA Physician Masterfiles would allow the creation and subsequent sale of physicians’ prescription profiling data used to microtarget compliant physicians and direct detail reps to soft targets, a process that would critically enable the progression of the opioid epidemic decades later.

Next: The Real Arthur Sackler. Part 5. Drug King Pin

The Real Arthur Sackler. Part 3 – Pfizer’s Agent of Record.

Posted on | September 25, 2019 | Comments Off on The Real Arthur Sackler. Part 3 – Pfizer’s Agent of Record.

Mike Magee

Series Note: This 5-Part Series will run from September 23rd to September 27, and then be available as a single document under Hcom Resources.It is based on original research in CODE BLUE: Inside the Medical-Industrial Complex.

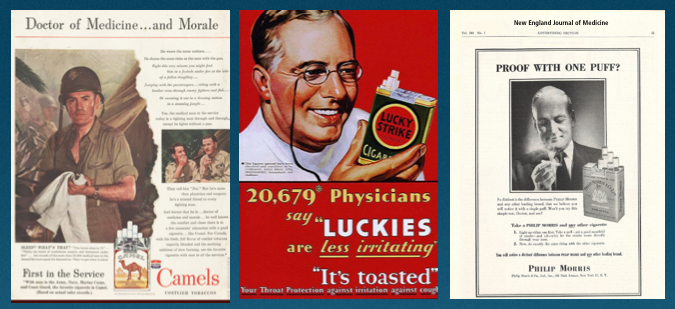

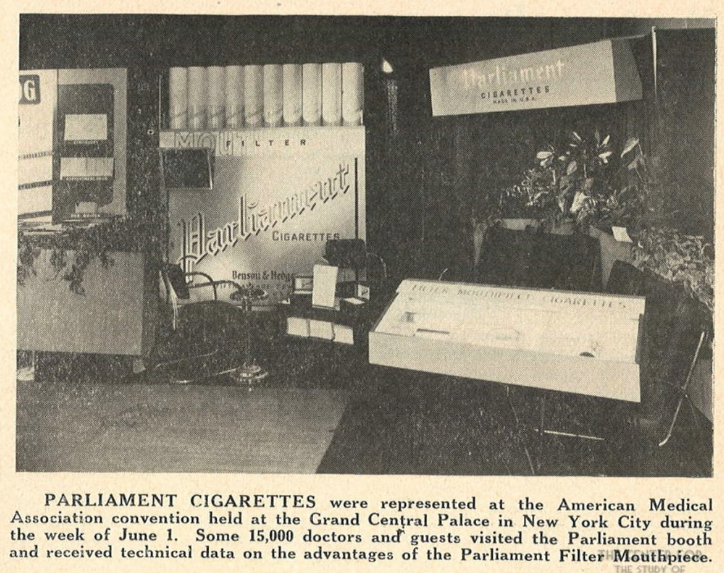

Throughout the 1940’s, the tobacco industry and the American Medical Association grew in size and influence, side by side. Tobacco ads featured the Army Medical Corps and laid conflicting claims which brand doctor soldiers favored.

The AMA enjoyed the financial support of tobacco advertising in JAMA, and at their conventions where the industry sponsored “smoking lounges” and elaborate quasi-scientific displays of new and improved tobacco filters.

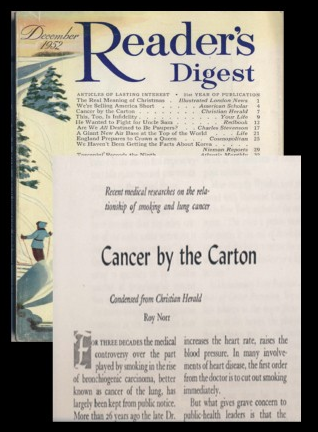

But in 1952, a single Reader’s Digest article entitled “Cancer by the Carton”, caused JAMA and the New England Journal of Medicine to change course, and distance themselves from tobacco money.

Waiting in the wings were pharmaceutical marketers anxious to advantage a huge burden of disease that accompanied returning soldiers. Between 1950 and 1957, advertising revenue in JAMA for pharmaceutical ads increased seven-fold. At the top of the list was Pfizer and its new antibiotic, Terramycin. Between 1950 and 1952, 68% of all JAMA broad spectrum antibiotic ads were funded by Pfizer. Between 1952 and 1956, nearly every JAMA issue included Pfizer’s in-house magazine titled “Spectrum”.

The push paralleled an increase in Pfizer detail men from 8 to 2000 (including medical students). They targeted doctors and hospital pharmacies, and developed a sophisticated range of Continuing Medical Education (CME) materials for the first time. Pfizer’s agency of record? The William Douglas MacAdams Advertising Agency. The principal on the account? Arthur M. Sackler.

Arthur’s groundbreaking innovations would, in the future, be enshrined in the Medical Advertising Hall of Fame. In the posthumous award, they stated, “In the late 1940s and 1950s, Rx companies were not marketing-oriented. They had small field forces and lacked extensive marketing resources. At this time, however, scientific breakthroughs in steroids, antibiotics, antihistamines, oral hypoglycemics, and psychotropics were revolutionizing medicine and creating a highly competitive market for brand-name prescription drugs. Dr. Sackler saw the important role non-personal selling could play in this environment and became an advocate for the full-blown marketing programs (field force plus multimedia promotional activities) employed today….It can be said that Dr. Sackler helped shape pharmaceutical promotion as we know it today (he even experimented with medical radio and TV in the 1950s), as well as established the role of communications and promotional programs in pharmaceutical marketing.”

The Hall of Fame also acknowledged that he used his psychiatric training quite effectively. As they said, “Dr. Sackler was a psychiatrist who published 140 scientific papers on neuroendocrinology, psychiatry, and experimental medicine.” What they didn’t mention is that the vast majority of these were self-published in journals and “medical newspapers” that Sackler himself had launched as promotional vehicles.

During this same period, his business dealings and associations were secretive and conspiratorial. He created hidden corporations, and listed them under his first wife to hide his own ownership. Behind the scenes, he colluded with his supposed arch-rival, agency head Bill Frohlich, whose company International Medical Statistics (IMS) would marry databases with the AMA physician masterfile, reselling the progeny to pharma companies, and allowing them to track individual physician prescribing behavior. His own secret ownership stake in IMS would be revealed after his death. But while alive, he quietly purchased the near dead pharmaceutical manufacturer, Purdue-Frederick, and mothballed it for future use.

In a single decade, Sackler also invented the pharmaceutical rep – a business attired professional “detail man” that would visit doctors offices with branded trinkets and provide the scientific details and new drug samples doctors needed to keep up; and launch pharmaceutical funded “scientific advisory boards” and speakers bureaus that would assist friends like heart surgeon Michael DeBakey as they climbed the integrated career ladder from academia to industry to government and back again.

In 1957, he aired the first drug advertorial on television, an extravaganza describing a new mysterious condition called “Ataraxia” which kept stressed out business men in a state of psychic distress preventing sleep and relaxation. Sadly, no cure was mentioned in the broadcast. That came a few months later when Pfizer released their new tranquilizer, Atarax.

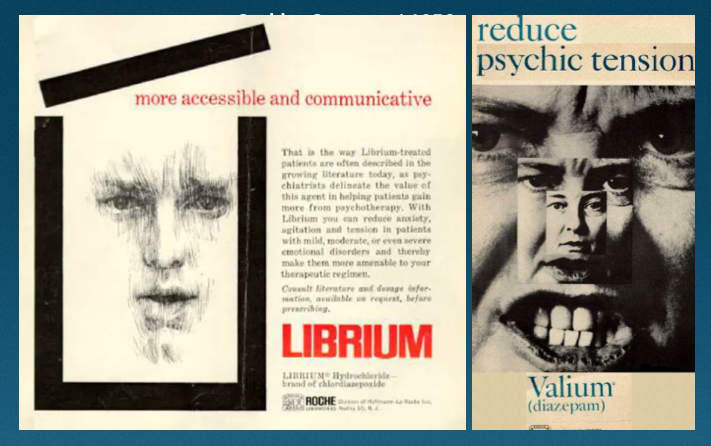

By 1960, he represented two new drugs that risked cannibalizing each other – Valium and Librium. He skillfully promoted one for nervous tension and the other for psychic stress, making both record breaking success stories. By then, 1 in every 7 Americans were on tranquilizers.

But for Arthur, this was just the beginning. He had a grander vision, and had already laid the seeds that would create wealth beyond his wildest dreams, and eventually threaten the health and stability of our nation.

Next, Part 4: The Visionary Data Manipulator.