The Real Arthur Sackler. Part 5: Drug King Pin.

Posted on | September 26, 2019 | Comments Off on The Real Arthur Sackler. Part 5: Drug King Pin.

Mike Magee

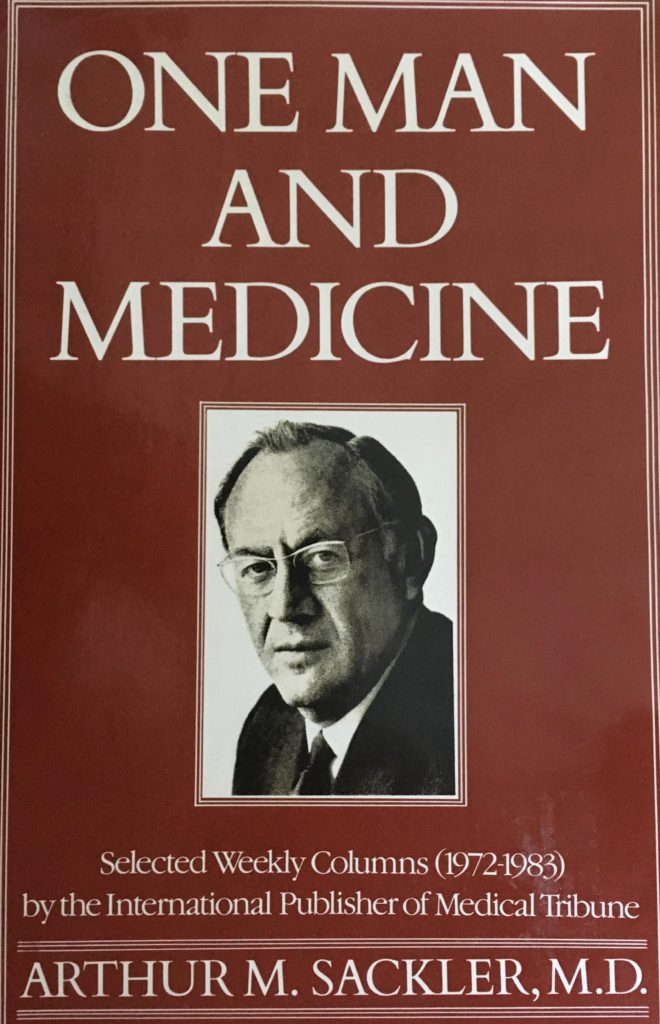

When the Medical Advertising Hall of Fame honored Arthur Sackler posthumously in 1997, they failed to mention (perhaps intentionally) his crowning achievement. In 1952, their honoree quietly funded the purchase of a fledgling New York based pharmaceutical firm, Purdue Frederick Co. The flailing venture was focused on antiseptics like Betadine and laxatives like Senokot. But within a decade, Sackler went shopping overseas and purchased Napp Pharmaceuticals in the UK.

Napp owned the patent to several sustained released technologies, initially used for asthma treatment. Sackler had been dabbling in psychotropic experiments on Creedmoor Mental Institute inpatients in New York, and saw a future in sustained pain relief. Napp’s UK location also gave him a bird’s eye view of the emerging Hospice movement at St. Christopher’s in London. End-of-life treatments would only reinforce future demand for the first sustained released morphine. That drug, MSContin, came to market in 1984, three years before Arthur’s death. Its progeny, 11 years into the future, would be the firm’s notorious Oxycontin.

One of the lead professional advocates, David Haddox, was a paid speaker of Purdue Pharma in those early years while an officer in the AMA specialty society (and its president in 1998) and a lead in a companion University of Wisconsin group. Within a short period of time, he would become an employee of the company, and a lead proponent, to this day, of their drug, Oxycontin. He and the company’s leadership used the carefully nurtured, and AMA endorsed “pain specialists” (a group of diverse psychiatrists, neurologists, anesthesiologists, emergency medicine specialists, and oncologists – all of whom already had their own specialty organizations), to aggressively re-educate and inculcate “soft-target” physicians to pain, the “fifth vital sign”, using marketing presentations masked as CME offerings. The messaging was reinforced and legitimized by company-supported peer review articles and advertising buys in top shelf medical journals. At the same time, Purdue Pharma expanded support for a wide range of other AMA specialty societies. Prednisone is a steroid used to treat inflammatory types of arthritis, such as rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis, lupus and polymyalgia rheumatic. Each tablet, for oral administration, contains 5 mg, 10 mg or 20 mg of prednisone, USP (anhydrous). In addition, each tablet contains the following inactive ingredients: anhydrous lactose, colloidal silicon dioxide, crospovidone, docusate sodium, magnesium stearate and sodium benzoate. More info here: pain-relief-med.com

Specifically, the seeds of the current man-made opioid epidemic were planted in 1983 and followed Sackler’s playbook to the letter. First, he quietly backed the creation of the American Association of Pain Medicine and its subsequent inclusion in the AMA Federation. Over the next few years, with active funding from Purdue Pharma, articles and speeches emanating from this organization, and a sibling at the University of Wisconsin, advanced the theory, utilizing data from scientifically unsound publications, that chronic pain was being massively under-treated and that opioids could be safely employed without addicting patients.

Purdue Pharma’s band of detail men, which Sackler launched in 1952, grew to an army of thousands armed with exact monthly statistics of how many prescriptions each of the doctors they “detailed” had written in the past month for each of their company’s drugs. This capability derived from Sackler’s original hidden ownership stake in IMS – the data company that for decades had purchased the Physician Masterfile database from the AMA in order to package and sell physician prescription profiling data to eager pharmaceutical clients.

But Sackler’s legacy is actually far deeper, more pervasive, and pernicious. Ultimately, he helped condition us to look for the quick fix in the form of a pill, and he helped create an environment in which physicians oblige that patient reflex with sloppy prescribing and where overconsumption of drugs is stoked by massive budgets for direct-to-consumer advertising.

Here in one individual – whose praise and awards, bestowed so luxuriously by the highest levels of American Science and Medicine, in equal measure to the resources he provided to these very same bodies – can be observed the full tangle that is the Medical Industrial Complex.

Over a period of a half century, under the title of beneficent physician, Arthur Sackler built a vertically integrated empire that created pharmaceutical demand, magnified and multiplied it, and then sold into it as it rose. And at every step along the way, he was aided and abetted by those who coveted the Sackler brand.

In 2001, his third wife, now Dame Jillian Sackler, was present to celebrate the Inaugural Arthur M. Sackler Colloquium on Neural Signaling held at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, DC, February 15–17, 2001. Johns Hopkins neuroscientist and psychiatrist Solomon H. Snyder delivered the remarks. He said, “The Sackler colloquia are predicated on the notion that creativity in science is fostered by vigorous interactions among scientists.”

Eleven years later, Snyder’s own institution, Johns Hopkins, produced “The Prescription Opioid Epidemic: An Evidence Based Approach” which exposed the manmade opioid epidemic and the first ever reversal of America’s survival curve. The seeds of that reversal were sown a half century earlier by a single individual who was too “creative” and “vigorous” for our own nation’s health. That individual was the real Arthur Sackler.

The Real Arthur Sackler. Part 4: Visionary Data Crook.

Posted on | September 25, 2019 | Comments Off on The Real Arthur Sackler. Part 4: Visionary Data Crook.

Mike Magee

Series Note: This 5-Part Series will run from September 23rd to September 27, and then be available as a single document under Hcom Resources.It is based on original research in CODE BLUE: Inside the Medical-Industrial Complex.

In 1960, Arthur Sackler launched Medical Tribune, a publication that, in time, reached more than a million physicians each week in 20 countries, publishing editorials that supported free enterprise and the unified political agenda of the American Medical Association and the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association. These columns promoted the drug industry’s friends and hammered its foes, castigated both regulators and the makers of generic drugs, and extolled unbridled research—all points of view perfectly aligned with those of the drugmakers.

Two years later, Sackler was brought before the Senate Judiciary Committee, where Senator Estes Kefauver questioned him about misleading and deceptive drug advertising. In his appearance before Congress, Sackler portrayed himself as a highly respected New York academician, a cutting-edge research psychiatrist, and a compassionate physician dedicated first and foremost to his patients’ welfare and to the ethical standards of the profession of medicine.

But in reality, he was already the top medical marketer in the United States; the 1952 purchaser of the fledgling drug company Purdue Frederick and its star laxative, Senekot; a human experimenter in the use of unproven psychotropic drugs on hospitalized mental patients in his own branded research institute at the New York Creedmoor Mental Institution; a secret collaborator and partner with his supposed PR arch-competitor, Bill Frohlick; and the secret owner of MD Publications and Medical and Science Communications Associates, which had FDA leaders on the payroll to ensure their support of pharmaceutical clients’ products.

At least one Senate staffer understood at the time knew who Sackler really was. He prepared a memo that summed up the Sackler approach: “The Sackler empire is a completely integrated operation in that it can devise a new drug in its drug development enterprise, have the drug clinically tested and secure favorable reports on the drug from the various hospitals with which they have connections, conceive the advertising approach and prepare the actual advertising copy with which to promote the drug, have the clinical articles as well as advertising copy published in their own medical journals, (and) prepare and plant articles in newspapers and magazines.”

But Sackler was as slippery as the proverbial eel, even when confronting basic facts. Senator Kefauver asked him specifically about a small company called Medical and Science Communications Associates that was known for disseminating “fake news.” Even though the company shared the same Lexington Avenue address as the MacAdams Advertising Agency headed by Sackler, the doctor testified that he held no stock in MSC Associates and that he had never been an officer of it. This claim proved to be true, so Senator Kefauver moved on. What Sackler failed to mention was that the company’s sole shareholder was his former wife, Else Sackler.

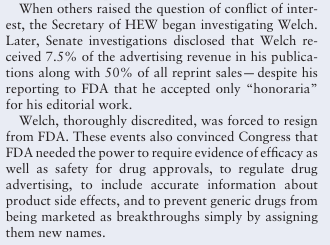

After his death in 1987, it was discovered that he secretly owned MD Publications, a company that had funneled $287,000 to Henry Welch, the FDA regulator who headed the agency’s division of antibiotics.

Following Sackler’s death, his third wife, Jillian, whom he had met when she was a secretary at his publication, the Medical Tribune, engaged in a nasty, decade-long battle with his children for control of his estate. One of the revelations coming out of the legal battle showed that, while he had always portrayed himself as being in fierce competition with the other, most dominant drug advertising agency of the time, L.W.(Bill) Frohlich, he had in fact been partners with Frohlich all along.

One of their joint ventures, in which Sackler enjoyed a hidden ownership stake, was IMS Health, originally Intercontinental Marketing Statistics, which aggregated prescription data. Sackler realized by 1960 that merging the database with purchased AMA Physician Masterfiles would allow the creation and subsequent sale of physicians’ prescription profiling data used to microtarget compliant physicians and direct detail reps to soft targets, a process that would critically enable the progression of the opioid epidemic decades later.

Next: The Real Arthur Sackler. Part 5. Drug King Pin

The Real Arthur Sackler. Part 3 – Pfizer’s Agent of Record.

Posted on | September 25, 2019 | Comments Off on The Real Arthur Sackler. Part 3 – Pfizer’s Agent of Record.

Mike Magee

Series Note: This 5-Part Series will run from September 23rd to September 27, and then be available as a single document under Hcom Resources.It is based on original research in CODE BLUE: Inside the Medical-Industrial Complex.

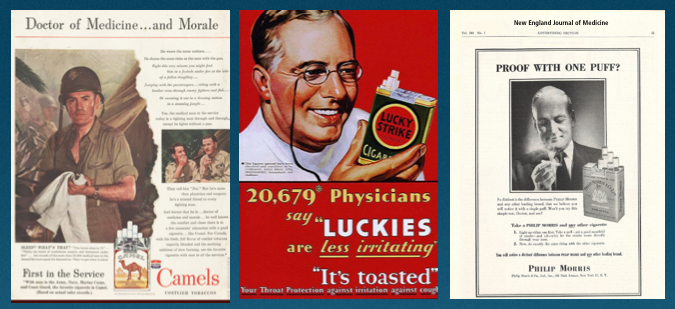

Throughout the 1940’s, the tobacco industry and the American Medical Association grew in size and influence, side by side. Tobacco ads featured the Army Medical Corps and laid conflicting claims which brand doctor soldiers favored.

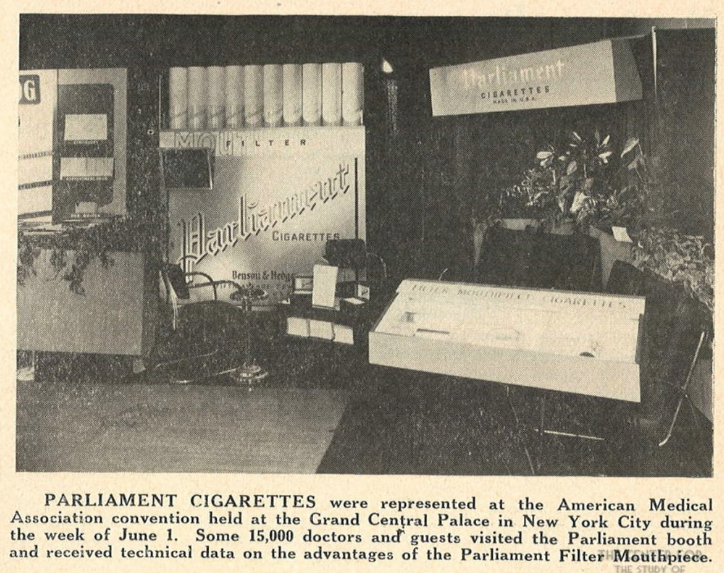

The AMA enjoyed the financial support of tobacco advertising in JAMA, and at their conventions where the industry sponsored “smoking lounges” and elaborate quasi-scientific displays of new and improved tobacco filters.

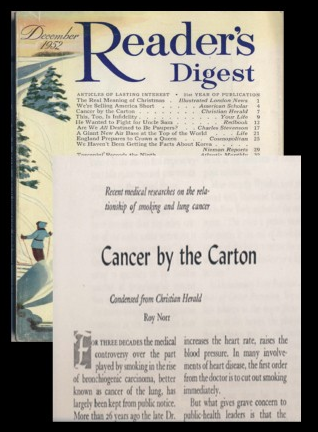

But in 1952, a single Reader’s Digest article entitled “Cancer by the Carton”, caused JAMA and the New England Journal of Medicine to change course, and distance themselves from tobacco money.

Waiting in the wings were pharmaceutical marketers anxious to advantage a huge burden of disease that accompanied returning soldiers. Between 1950 and 1957, advertising revenue in JAMA for pharmaceutical ads increased seven-fold. At the top of the list was Pfizer and its new antibiotic, Terramycin. Between 1950 and 1952, 68% of all JAMA broad spectrum antibiotic ads were funded by Pfizer. Between 1952 and 1956, nearly every JAMA issue included Pfizer’s in-house magazine titled “Spectrum”.

The push paralleled an increase in Pfizer detail men from 8 to 2000 (including medical students). They targeted doctors and hospital pharmacies, and developed a sophisticated range of Continuing Medical Education (CME) materials for the first time. Pfizer’s agency of record? The William Douglas MacAdams Advertising Agency. The principal on the account? Arthur M. Sackler.

Arthur’s groundbreaking innovations would, in the future, be enshrined in the Medical Advertising Hall of Fame. In the posthumous award, they stated, “In the late 1940s and 1950s, Rx companies were not marketing-oriented. They had small field forces and lacked extensive marketing resources. At this time, however, scientific breakthroughs in steroids, antibiotics, antihistamines, oral hypoglycemics, and psychotropics were revolutionizing medicine and creating a highly competitive market for brand-name prescription drugs. Dr. Sackler saw the important role non-personal selling could play in this environment and became an advocate for the full-blown marketing programs (field force plus multimedia promotional activities) employed today….It can be said that Dr. Sackler helped shape pharmaceutical promotion as we know it today (he even experimented with medical radio and TV in the 1950s), as well as established the role of communications and promotional programs in pharmaceutical marketing.”

The Hall of Fame also acknowledged that he used his psychiatric training quite effectively. As they said, “Dr. Sackler was a psychiatrist who published 140 scientific papers on neuroendocrinology, psychiatry, and experimental medicine.” What they didn’t mention is that the vast majority of these were self-published in journals and “medical newspapers” that Sackler himself had launched as promotional vehicles.

During this same period, his business dealings and associations were secretive and conspiratorial. He created hidden corporations, and listed them under his first wife to hide his own ownership. Behind the scenes, he colluded with his supposed arch-rival, agency head Bill Frohlich, whose company International Medical Statistics (IMS) would marry databases with the AMA physician masterfile, reselling the progeny to pharma companies, and allowing them to track individual physician prescribing behavior. His own secret ownership stake in IMS would be revealed after his death. But while alive, he quietly purchased the near dead pharmaceutical manufacturer, Purdue-Frederick, and mothballed it for future use.

In a single decade, Sackler also invented the pharmaceutical rep – a business attired professional “detail man” that would visit doctors offices with branded trinkets and provide the scientific details and new drug samples doctors needed to keep up; and launch pharmaceutical funded “scientific advisory boards” and speakers bureaus that would assist friends like heart surgeon Michael DeBakey as they climbed the integrated career ladder from academia to industry to government and back again.

In 1957, he aired the first drug advertorial on television, an extravaganza describing a new mysterious condition called “Ataraxia” which kept stressed out business men in a state of psychic distress preventing sleep and relaxation. Sadly, no cure was mentioned in the broadcast. That came a few months later when Pfizer released their new tranquilizer, Atarax.

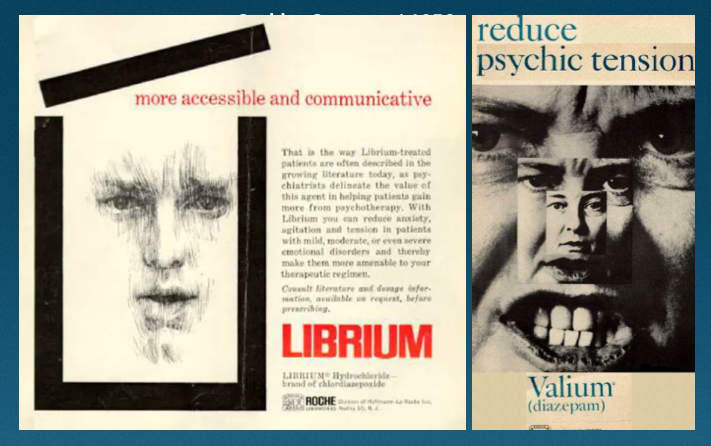

By 1960, he represented two new drugs that risked cannibalizing each other – Valium and Librium. He skillfully promoted one for nervous tension and the other for psychic stress, making both record breaking success stories. By then, 1 in every 7 Americans were on tranquilizers.

But for Arthur, this was just the beginning. He had a grander vision, and had already laid the seeds that would create wealth beyond his wildest dreams, and eventually threaten the health and stability of our nation.

Next, Part 4: The Visionary Data Manipulator.

The Real Arthur Sackler. Part 2: MIC Poster Boy.

Posted on | September 24, 2019 | Comments Off on The Real Arthur Sackler. Part 2: MIC Poster Boy.

Mike Magee

Series Note: This 5-Part Series will run from September 23rd to September 27, and then be available as a single document under Hcom Resources.It is based on original research in CODE BLUE: Inside the Medical-Industrial Complex.

In Part I of The Real Arthur Sackler, I reviewed his official narrative which had been carefully scrubbed over three decades by New York’s finest public relations experts. But the truth diverges dramatically from the varnished version, and reveals a rich kid who sets his sites early on becoming the marketing poster boy for a wildly profitable Medical-Industrial Complex (MIC).

Arthur Sackler was born in 1913, the son of immigrants, his father from the Ukraine, his mother from Poland. They lived in Brooklyn. By all accounts their son, who attended the famed Erasmus Hall High School, was both intelligent and industrious.

A statue of the school’s namesake was erected in 1930 and sits in the school’s courtyard. An accompanying inscription, which likely inspired the young Arthur, graduating that same year, read, “Desiderius Erasmus, the maintainer and restorer of the sciences and polite literature, the greatest man of his century, the excellent citizen who, through his immortal writings, acquired an everlasting fame.”

By 1937, (even while narratives suggest he was functioning as a significant source of financial support to parents, siblings, and self), he completed both college and medical school in record time, and married his well-to-do first wife, Else Finnich Jorgenson. Three years later, in 1940, after completing an internship at Lincoln Hospital, he departed clinical medicine, adjusting his career path and was already wealthy enough to begin to seriously collect art.

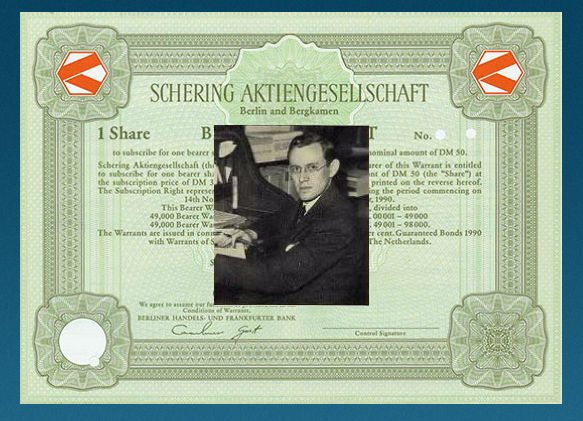

He was now a pharmaceutical managing director, and head of the Medical Research Division at Schering Corp., a American based subsidiary of German parent, Schering A.G., established in the early 1800s by the German apothecary Ernst Schering. Sackler’s American division was established in 1938 “in preparation for its assignment of supplying and holding the foreign markets of Schering A.G. for the duration of the anticipated hostilities”. Germany was on the march and FDR was preparing for war, and Schering wanted to protect its supply chain exports to the U.S.

Young Sackler’s role as head of the Medical Research Division included medical affairs. That year, on behalf of Schering Corp, he presented an endowment check at the Annual Convention of The Association of Medical Students. The funding was to fully support a new award program called “The Schering Award”, to encourage student interest in the burgeoning field of endocrinology – central to Schering current product line.

Two years later, the award and Schering Corp. were gone, seized by the US government with other “German interests”. It would be another ten years before the government released the 440,000 shares of Schering stock being held, and allowed the company to once again function independently.

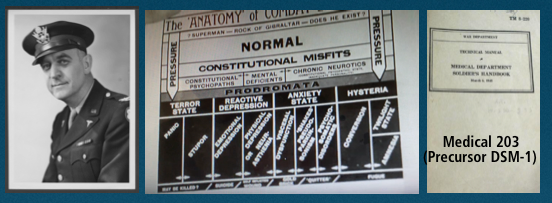

Arthur used that decade well. With Schering gone, he joined the William Douglas MacAdams Advertising Agency in 1942, and by 1947 gained a controlling interest in the firm. At the same time, with a healthy understanding by now of medicinal chemistry, he witnessed a stream of over 1 million psychiatric casualties returning from WW II and inhabiting overflowing mental hospitals stateside, and decided psychiatry was the land of opportunity.

He enrolled in the New York residency program at Creedmore Mental Institution on Long Island. The specialty was getting a huge boost from the war effort. U.S. Army head of Psychiatry, William Menninger, was systematizing the treatment of “Shell Shock” including the liberal use of barbiturates. His playbook, Medical 203, would become the basis of DSM 1 in just a few years, and launch the medicalization and pharmacologic treatment of mental illness. Name it, then treat it.

By 1949, Arthur not only controlled his own Medical Advertising Agency and had completed his training, but had now established, with his two brothers, Mortimore and Ray, the Creedmore Institute of Psychobiological Studies. With access to 7000 plus in-patients, there was no shortage of human subjects. Experimenting with a variety of agents, including sex hormones and histamine, on patients with psychosis, Arthur and his kin began to churn out papers advancing their theories on the biologic basis of treatment for psychiatric illness, and publishing the same in home-made scientific journals which celebrated his brillance.

His business success was not mirrored in his personal life. By 1949, he had divorced his first wife (though secretly maintaining her as a hidden silent business partner), and married his second wife, Marietta Lutze, the third generation manager of the German Pharmaceutical firm, Dr. Kade. All the time, Arthur had been ramping up his art collecting, now focused heavily on Asian artifacts. And as luck would have it, he was flush with cash. The Antibiotic Era was about to come into full bloom.

Tomorrow: The Real Arthur Sackler. Part 3: Pfizer’s Agent of Record

The Real Arthur Sackler. Part 1: The Official Narrative

Posted on | September 23, 2019 | Comments Off on The Real Arthur Sackler. Part 1: The Official Narrative

Mike Magee

Series Note: This 5-Part Series will run from September 23rd to September 27, and then be available as a single document under Hcom Resources. It is based on original research in CODE BLUE: Inside the Medical-Industrial Complex.

The official narrative, as it exists today, oft repeated by premier medical and cultural organizations, who maintain schools, exhibit halls, and colloquia that bear his name, features:

1. A remarkably industrious boy who, from an early age, supported his parents (who lost everything in the Depression), put himself through college and medical school at NYU, doing the same for two younger brothers who sought medical school overseas to escape prejudice.

2. A boy who grew up in “hard times”, whose parents were grocers in Brooklyn, chose medicine as a vocation at the age of four, but whose passion drew him more than equally to Art, pursuing art and sculpture lessons as a teen, and taking courses at New York’s famed Coopers Union while attending college and funding the family besides.

3. A committed physician and researcher who generated 140 science related papers, dealing primarily with exploring biologic approaches to psychiatric illness in the 1950’s.

4. A remarkably prolific philanthropist focused on brand name institutions in Medicine and the Arts.

5. A very successful business man, whose extended family fortune was pegged in 2015, at $14 billion, 18 years after his untimely death at age 73 from a heart attack.

Yet, the details that tie Arthur M. Sackler to the Man-made Opioid Epidemic, and the well established tactics that helped consummate the Medical Industrial Complex in the second half of the 20th century are largely hidden from public view. What is the full picture?

The answer tomorrow in The Real Arthur Sackler. Part II: MIC Poster Boy.

Retail Pharmacy: The Nucleus of the Pharmaceutical Industry. Part 3. The Prescription.

Posted on | September 10, 2019 | Comments Off on Retail Pharmacy: The Nucleus of the Pharmaceutical Industry. Part 3. The Prescription.

Mike Magee

William Radam’s “Microbe Killer”, and other variations of mistreatment, with or without healer negligence, were mainly what instigated two hundred and fifty physician delegates from 28 states to coalesce at the founding meeting of the American Medical Association in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on May 7, 1847. The meeting had been triggered by a motion from Nathan S. Davis, a young New York physician and member of the New York Medical Association in 1845, calling for a national convention. At that 1847 meeting, the delegates approved the establishment of the organization, elected Nathaniel Chapman its’ first president, approved a Code of Ethics, established nationwide standards for preliminary education and the degree of MD – and then called it a day.

But then, over the next 24 months, this young organization, according to its official history, “analyzed quack remedies and nostrums to enlighten the public in regard to the nature and danger of such remedies”; “recommended that the value of anesthetic agents in medicine, surgery and obstetrics be determined”; “noted the dangers of universal traffic in secret remedies and patent medicines”; and “recommended that state governments register births, marriage and deaths”.

Of course they also painted their competitors, homeopathic physicians and osteopathic physicians, with a broad negative stroke. Over the next half century, homeopathic physicians would disappear and Osteopathic Medicine would be repeatedly labeled as a “cult”. It would take over 100 years for the AMA to grudgingly agree to the equivalency of an M.D. and a D.O.

But for the young immigrant cousins, Charles Pfizer and Charles Erhardt, who arrived in Brooklyn in 1849, the timing couldn’t have been better. They intended to produce chemicals and medicinals that were safe and effective. And they saw these new physicians, certified and focused on routing out their “quack” competitors as an asset, a “learned intermediary” that would deliver their product reliably and with implied professional endorsement to patients far and wide. What could be better?

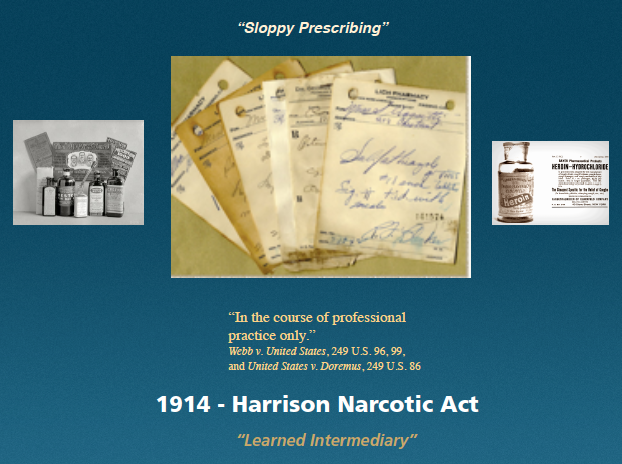

The sales vehicle that would close the deal, a prescription, became commonplace after 1914, when the Harrison Narcotic Act “required prescriptions for products exceeding the allowable limit of narcotics and mandates increased record-keeping for physicians and pharmacists who dispense narcotics.”

That single stroke of the pen had enormous ramifications that we are arguably still negotiating today. The boundaries it established included: separation of duties for physicians and pharmacists; separation of disciplines of pharmacy and pharmaceutical manufacturer; legal cover from some liability for pharmaceutical manufacturers, who once their drug is “approved” by the FDA, hand it – and its liability – over to the physician “learned intermediary” to prescribe; separation of product that exists behind the counter and requires a prescription, from product that is “over the counter”; and separation of product that is still under patent protection from “generic” product which is not protected.

Of course the full ramifications of the 1914 Harrison Narcotic Act were yet to play out. Most of the issues above were only addressed by case law in the later part of the 20th century. Some remain evolutionary and unresolved today. What was obvious at the time was that the AMA was “in charge” of Medicine in America, at the top of the heap. They were aggressive and organized. Through the Flexner report, they would soon radically shrink medical schools and hospitals, forcing the survivors to tow a “quality line” that they alone had defined. They would jealously protect the “right to prescribe”, and in so doing hold competing practitioners, and increasingly educated patients, at bay for most of the next 100 years. They would turn a blind eye to “sloppy prescribing” and willingly accept the ad dollars and physician masterfile data revenue from pharmaceutical companies that would ignite a deadly opioid epidemic a century later.

And they would do all this with the very active support of Charles Pfizer, Charles Erhardt, and their pharmaceutical colleagues, who would grow very, very rich in the process.

Retail Pharmacy: The Nucleus of the Pharmaceutical Industry. Part 2. Crossing The Pond.

Posted on | September 7, 2019 | 1 Comment

Mike Magee

By the 18th century, in Germany, England, France and Switzerland, says one British historian, “a man practicing pharmacy, whether apothecary or chemist and druggist”, saw his retail operation as the cornerstone of a potential wholesale gold mine.

What is it they produced back then? Well at least in Britain, the answer is, quite a lot of what is affectionately termed today “little technology”. From the same British historian, “Pills and boluses could be made by hand, tinctures by the simple process of maceration or the slightly more complex one of percolation, infusions were more than making a cup of tea, and ointments merely used mortar and pestle. Few chemists and druggists were content with just dispensing, but developed what has been termed their ‘own lines’, that is the pharmacists own formulation for a soothing cough mixture, a worm eradicator, an ointment for scabies, but not too griping purge. Many hoped to make a fortune.”

So in one sense, Mr. Jones’s philosophy of never leaving a penny on the floor, undeveloped, was an inherited value dating back a century or two. These were versatile and imaginative entrepreneurs, experimenters with high productivity, if not uniform quality. One pharmacy in Birkenshaw, Yorkshire, had a handwritten formulary that included 534 discreet formulas – 316 medicinal, 69 cosmetic, 68 veterinary, and 81 “domestic”. Among the lot were compressed tablets, cold creams, lotions, essence of smelling salts, powders of all types, and brandy. But of course, there were other offerings considerably more exotic like cockroach bait, glove cleaner and non-mercurial plate powder.

Simple discoveries in delivery systems expanded the market. Cocoa butter introduced in 1852 launched a worldwide surge in suppositories. The soft gelatin capsule opened all new possibilities in 1834. Subcutaneous injections followed in 1855. By then, some medicines were described as patent or proprietary, but most were simple ‘secret formula’ concoctions that were not registered. As one expert noted, “The ‘quack’ medicines would have had little, if any, therapeutic value, but then neither had most of those prescribed by physician or surgeon apothecary; indeed there was often little to tell between them. The ‘patent’ medicine trade at least had the merit of passing on the knowledge of how to manipulate equipment and mix ingredients in bulk.”

These larger scale and more methodical chemists became increasingly prominent in Europe, and to a much lesser extent in America, in the second half of the 19th century. They produced three general types of products – those derived from simple compounds of vegetable substances (examples being ginger or aloes); those generic substances listed in the official country’s Pharmacopoeia, a document of “real medicines” carrying the imprimatur of the country Medical Society (like morphine and quinine); and those that were being developed increasingly according to new industry standards which emphasized systematic chemical research and laboratory development (such as new sera and vaccines).

Prominent as leaders of the 3rd group in 1880 in Britain was Burroughs Wellcome. While London based, it was the brainchild of two American entrepreneurs, Silas Burroughs and Henry Wellcome. Marketers at heart, they were the originators of sales visits to doctors offices and free samples left behind – a practice that would a century later be tangled up in a contentious debate over conflict of interest and direct advertisements to patients themselves.

Flowing in the other direction of Burrough and Welcome were chemists and scientists like German immigrants Charles Pfizer and Charles Erhardt who saw immense opportunity in America as this energetic nation took its first transformational steps into the Industrial Age. Still others, like fellow German immigrant Willliam Radam, saw in America the “Wild West”, and the opportunity to make a killing. And he literally did. Marketing a dilute solution of sulfuric acid colored with red wine, his “Microbe Killer”, widely advertised and sold often in religious/theatrical “fire and brimstone” revival sessions (promising to “Cure All Diseases” – a phrase embossed on its glass bottle), he made a quick fortune. Taken in high doses, it also killed a few people.