June 9, 1954 – The Day America Slayed The Dragon.

Posted on | June 21, 2022 | Comments Off on June 9, 1954 – The Day America Slayed The Dragon.

Mike Magee

If you plan on tuning in to the 4th session of the January 6 Congressional hearings at 1 PM EST today, do yourself an enormous favor. Commit five minutes this morning to view a 5 minute online video of a Congressional hearing which is a Master class in “How to slay a dragon.”

The clip does not feature John Dean and his reading of a 245-page prepared summary on June 25, 1973 where he recounts advising Nixon of “a cancer on the presidency.” Nor is it a cameo of surprise witness, Alexander Butterfield, on July 16, 1973, revealing that the President maintained a taping system in the Oval Office.

No. This is from an earlier time. The date is June 9, 1954. This was over a year after Wisconsin Republican Senator Joseph R. McCarthy had assumed the chairmanship of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. The history shows that he had “rocketed to public attention in 1950 with his allegations that hundreds of Communists had infiltrated the State Department and other federal agencies.” Clearly a psychopath, he escaped control of moderating voices, biting off ever larger targets, including now the U.S. Army.

“Judge, jury, prosecutor, castigator, and press agent, all in one”, was how Harvard law dean Ervin Griswold described him. In 1954, McCarthy accused the army of “lax security at its top-secret army facilities” which he claimed were infiltrated by communists. The army responded by hiring veteran Boston lawyer Joseph Welch to defend itself.

As documentarians reported, “Mothers who never watched TV during the day were glued to watching the Army-McCarthy hearings.” McCarthy’s right-hand chief council that day was none other than Trump’s most favored personal bro-lawyer Roy Marcus Cohn. Pragmatic, ruthless, and evil to the core, Cohn’s career was launched by McCarthy, and his tainted touch destroyed lives and weakened the U.S. government for three more decades, straight up to the moment of his death from HIV/AIDS in 1986.

In this 5-minute summation of the televised events of June 9, 1954, you are allowed to witness an historic takedown of McCarthy by Welch (with Cohn as witness) – the “slaying of the dragon” that finally destroyed McCarthy once and for all. Cohn had reached an agreement with Welch that McCarthy would avoid attacking one particular Army service man as a communist if Welch remained civil. But Welch had laid a trap, and purposefully needled McCarthy into loosing his temper, and on camera, violating the agreement and “attacking the good lad”, who an outraged Welch tearfully defended in his historic and well-prepared retort.

As historian Thomas Doherty recalls, “It was as if the entire country had been waiting for somebody to finally say this line, ‘Have you no sense of decency.’” To which Jelani Cobb adds, “At the end of it, all the illusions, the comfortable illusions that McCarthy had cultivated about himself, had effectively been dispelled.”

Watch Welch pounce on his victim. Watch Cohn wince as his dragon is slain. Liz Cheney has likely viewed these 5 minutes more than once.

Tags: cohn > January 6 congressional hearings > Joe McCarthy > Joseph Welch > slay the dragon > trump

Patients Are Piling Up Credit Card Debt – Doctors, Hospitals, CVS*, and Other Grifters.

Posted on | June 20, 2022 | Comments Off on Patients Are Piling Up Credit Card Debt – Doctors, Hospitals, CVS*, and Other Grifters.

The Medical-Industrial Complex is swarming with grifters. This is to be expected when you build a purposefully complex system designed to advance profitability for small and large players alike. The $4T operation bankrolling 1 in 5 American workers is, in large part, a hidden economy, one built by professional tricksters, designed by Fortune 100 firms with mountains of lobbyists, but reinforced as well by friendly doctors and hospitals engaged in petty and small scale swindling who justify their predatory actions as entrepreneurial, innovative, and purposeful means of necessary financial survival.

When lobbyists for high-priced stakeholders get called before Congress, as they did on March 29, 2022 before the House Committee on Oversight and Reform, they make it sound like Americans should embrace the privilege of being screwed over by MIC elite. But as former Kaiser Permanente CEO, George Halvorson, recently reminded, “People are getting bankrupted when they get care, even if they have insurance.”

It’s enough to draw a person back to the early 1950’s when Arthur Sackler helped launch the Medical-Industrial Complex. In fact, our modern day willingness to mask health care cruelty in high-minded language and miscarry justice is extreme enough to draw one back to June 9, 1954, when Boston attorney, Joseph Welch, hired by the U.S. Army to defend it against accusations of Communist infiltration, said to Sen. Joe McCarthy, “Little did I dream that you could be so reckless and so cruel…You’ve done enough. Have you, sir, no sense of decency at long last?”

Halvorson and others seem to be reaching a similar boiling point, ready to utter to controllers and apologists of the MIC – “Have you not done enough?”

The most recent tipping point comes in the form of a June 16, 2022 KFF poll revealing that more than 100 million Americans, including 41% of all adults, carry significant medical debt, much of it out-of-sight, carried on personal credit cards. Hospitals and doctors have been tapping into the patients cards for payments, leaving patients tapped out, with high interest plastic debt. 1 in 8 now owe more than $10,000, which nearly 20% say they will never be able to pay off.

The problem is accelerating as health insurers have pushed skimpy plans with deductibles that can legally reach $8,700 a year per individual. As I documented with Tenet Health Care Systems and their Conifer Collection System in 2018, the debt business has bailed out poor hospital practices and medical group mismanagement more than once. Now four years later, 58% of collection agency listed debt is medical in nature. One in 10 of the desperate debtors owe money to family members, and collective medical debt now tops $195 billion as of 2019.

As if it couldn’t get worse, the debt (as one might expect) is not spread evenly. Southern states are over-represented due to poor insurance protection laws, lack of Medicaid expansion, and greater presence of chronic disease in their populations. Medical debt is 50% more common in Blacks, and 35% more common in Hispanics, than in whites. If you live in an unhealthy county (measured by high rates of chronic diseases), 1 in 4 have medical debt, compared to 1 in 10 in healthy counties.

Of course, if you are unhealthy in the U.S., you are also in the cross-hairs of direct-to-consumer drug advertising. The practice of pushing medications through TV ads is only allowed in one other nation in the world.

More than 1 in 3 Americans will fill those prescriptions at CVS, where whistleblower, Alexandra Miller used to work. What is she blowing her whistle about? According to STAT’s uber-pharma investigative reporter, Ed Silverman, her lawsuit contends that “Starting in 2015, CVS allegedly coordinated an effort that relied not only on its SilverScript (Medicare Part D) subsidiary, but also its Caremark pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) and its chain of CVS retail pharmacies to prevent consumers from obtaining low-cost generics because the company profited from making only higher-priced brand-name medicines available to its customers….”

The kickback scheme involved CVS Health’s Part D plan sponsor, SilverScript; its pharmacy benefit manager, CVS Caremark, and CVS Pharmacies with hidden rewards flowing back and forth as patients credit card debt skyrocketed. As America proceeds headlong into a recession, and the economy becomes bedridden, the ghost of Arthur Sackler is rising from its gilded crypt and whispering, “It is your own health care system that is making you sick and broke.”

Tags: alexandra miller > arthur sackler > collection agencies > Conifer > credit card debt > cvs > CVS Caremark > ed silverman > Joe McCarthy > Joseph Welch > kickbacks > medical debt > SilverScript > STAT > Tenet > whistleblower

As The Bird Flies (and the planet burns)…So Does The Risk of Infectious Disease Grow.

Posted on | June 14, 2022 | 2 Comments

Mike Magee

A study eight years ago, published in Nature, was titled “Study revives bird origin for 1918 flu pandemic.” The study, which analyzed more than 80,000 gene sequences from flu viruses from humans., birds, horses, pigs, and bats, concluded the 1918 pandemic disaster “probably sprang from North American domestic and wild birds, not from the mixing of human and swine viruses.”

The search for origin in pandemics is not simply an esoteric academic exercise. It is practical, pragmatic, and hopefully preventive. The origin of our very own pandemic, now in its third year and claiming more than 1 million American lives, remains up in the air. Whether occurring “naturally” from an animal reservoir, or the progeny of an experimental lab engaged in U.S. funded “gain-of-function” research, we may never know. What we do know is that viruses move at the speed of light, or more accurately, at the speed of birds.

When Tippi Hedren and Rod Taylor headed indoors at Bodega Bay, California in a high-speed attempted escape from sudden violent bird attacks in the Alfred Hitchcock 1963 natural horror-thriller film, The Birds, it was beaks not bugs they were trying to avoid. But sixty years later, we may all soon find ourselves nodding in agreement with the Library of Congress which declared Hitchcock’s work to be “culturally, historically, and aesthetically significant.” Tourists on the national mall two weeks ago would agree. They discovered a dozen dead mallard ducklings in the national Reflecting Pool. Vets quickly determined the cause – avian flu virus.

Last month’s Nature publication, written by science journalist Brittney J. Miller, titled “Why unprecedented bird flu outbreaks sweeping the world are concerning scientists,” raised the alarm. As she writes “Mass infections in wild birds pose a significant risk to vulnerable species, are hard to contain and increase the opportunity for the virus to spill over into people.”

In the past 9 months, an H5N1 bird flu strain has ignited 3,000 outbreaks in domestic poultry populations across the globe – from Europe, Asia, Africa, and North America. Local governments have limited the damage by destroying (culling) over 77 million birds. But these chickens and turkeys don’t fly commercial, so how did their virus spread?

The answer lies in the dead bodies of another 400,000 wild birds, mostly water fowl, involved in another 2,600 outbreaks in 2022. So far, the virus doesn’t seem to like humans much. Only two human cases (one in the U.K. and another in the U.S.) have been flagged. But spillover, say experts, is inevitable with spread at this rate. A WHO representative says, “These viruses are like ticking time bombs. Occasional infections are not an issue – it’s the gradual gaining of function of these viruses” that’s makes everyone nervous.

Since 1996, wild birds have been in the cross-hairs. Back then, a pathogenic H5N1 bird flu appeared in geese in Asia. Within 5 years, it was all over Europe and Africa. Five years later, widespread mass deaths of wild birds appeared tracked back to the original geese. Within another 10 years, a worrying trend evolved. A strain throughout North America appeared that infected a range of wild birds but didn’t always kill them. For example, mallard ducks were routinely infected, but only 10% died. While good for the ducks, their survival fueled continued spread and reengineering through mutation of the virus.

As you might imagine, it’s not as easy to track and monitor wild birds as well as cooped up chickens. Nor is killing them in masse once infected a reasonable, or achievable option. From the wild bird’s perspective, these are not the best of times. If you are a ruddy turnstone or a resident duck on the Delaware Bay, things are heating up in more ways than one.

Global warming is affecting the timing of horseshoe crab spawning season at the Delaware Bay.

The northern Arctic migration (with a stopover at the Delaware Bay) of the ruddy turnstone (which feeds on the crab) has been prolonged as a result. Many of these birds are bird flu carriers. The longer they hang around, the more they infect the local water fowl residents – especially, ducks, swans, geese, shorebirds, and waders. On top of this, when the ruddy turnstone and other migrators reach the Arctic, they are staying longer thanks to moderating temperatures and ice melting. Scientists have concluded that “these conditions support maximal transmissions (of viruses) across wild water birds.”

Climate change not only leads to northward shifts, but expanded species diversity, accompanied by shorter migratory routes. Both spell greater mixing and exchange of viruses across avian species. Spring migrations are now taking place earlier, with age classes, species and flyways significantly altered. Extreme climatic events, more common in an age of “global weirding” of weather, are also more common. For example, a cold clip near the Caspian Sea in 2006 triggered a mass exodus of swan, which unleashed an H5N1 viral outbreak in domestic birds across Western Europe.

What ecologists are saying is that “A1 viruses have co-evolved with migratory waterfowl over millions of years and have survived and withstood many eras of climatic turbulence… An increase in the proportion and number of birds over-wintering in the subarctic areas may result in very high densities of birds competing for the limited feed resources available. This could potentially enhance interspecies virus transmission, involve a larger spectrum of avian host species or alter the virus transmissibility, both to wild birds and domestic poultry.”

As more and more Canadian geese set up permanent domicile in the grassy wonderlands of suburban America, they and their wild avian friends are increasingly settled in, crowding together in a new world, permanently residing in intimate contact with humans. The shrill alarms set off by environmental scientists have now been joined and reinforced by an increasingly alarmed global infectious disease community.

Tags: 1918 flu > avian viruses > bird flu > Brittany J. Miller > CDC > changing migratory paths > covid > environmental science > global warming > infectious disease > Nature > pandemics

“Replacement Theory” from the BMJ

Posted on | June 8, 2022 | Comments Off on “Replacement Theory” from the BMJ

White Americans are dying (being “replaced”) at an alarming rate in Republican-led states since 2008? What’s the story?

Mike Magee

_____________________________________________________

“As I’ve said before, I believe Dr. Ladapo is an anti-science quack who doesn’t belong anywhere near our state’s Surgeon General office, let alone running it. But now that he’s been confirmed, it’s my sincere hope that he and Governor DeSantis choose to focus on saving lives and preventing unnecessary illness instead of continuing their absurd promotion of conspiracy theories and opposition to proven public health measures — but I’m not going to hold my breath.”

If you identified these as the words of former governor, and now Congressman Charlie Crisp, currently running to retake the office he once held, you’d be wrong. These are the words of another state Democrat who is running a distant 2nd in the Democratic primary battle set for this summer.

Her name is Nikki Fried, Florida’s Agricultural Commissioner, and the only Democrat in his Cabinet. This is not the first time she’s tangled with DeSantis over Joseph Ladapo. She vigorously opposed his nomination in October, 2021, citing among other deficits promoting Covid misinformation, discriminating against Black farmers, and refusing to wear a mask at the request of State Senator Tina Policy who was undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer.

By all accounts, the health department that Dr. Ladapo is supposed to be surgeon generaling is a mess. An investigative report in this week’s Tampa Bay News, found that in the past seven months as Covid variant cases topped 80,000 per week in the state, public health officials failed to report back positive tests to nearly a quarter of those infected, and failed to include 3,000 cases of COVID-19 deaths in the states mortality stats. During this same period, Ladapo, who earned his reputation for incompetence as a Trump sycophant, recommended that the state’s health departments cease all COVID contact tracing.

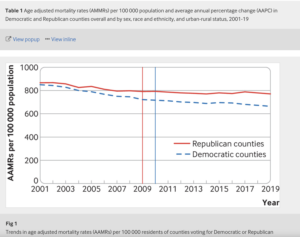

It would be comforting to imagine that politically motivated medical malfeasance is restricted to this one state, but a comprehensive article published this week in the BMJ, tracking U.S. health data from 2001 to 2019, finds that politics does indeed affect your health.

In a prior study published in JAMA the authors had established that there was a growing gap in morbidity and mortality between rural and urban areas in the U.S. As a follow-up, the lead author decided to explore whether county level political leadership affiliation positively correlated with poor medical outcomes.

In an article this week, the author, Haider J. Warraich, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, stated, “Regardless of whether we looked at urban or rural areas, people living in areas with Republican political preferences were more likely to die prematurely than those in areas with Democratic political preferences. There was no single cause of death driving this lethal wedge: The death rate due to all 10 of the most common causes of death has widened between Republican and Democratic areas… Based on statistical testing, the gap in mortality appeared to particularly widen after 2008, which corresponds to the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, a major part of which was Medicaid expansion.”

As expected, the poorest performing areas coincided with those under the control of Republican governors who refused to accept federally subsidized expansion of Medicaid services for their citizens.

While DeSantis and his fellow governors fan the flames of “replacement theory” and gratefully accept the unwavering support of the Trump base, they may want to focus on this surprise finding in the BMJ data – The “fourfold growth in the gap in death rates between white residents of Democratic and Republican areas seems to be driving most of the overall expanding chasm between Democratic and Republican areas.”

In 2005, I gave a speech at the Library of Congress that caused a stir. Its title was “Health is Political.” Dr. Warraich’s work adds concrete data in support of the argument. As he recently wrote, “In an ideal world, public health would be independent of politics. Yet recent events in the U.S., such as the Supreme Court’s impending repeal of Roe v. Wade, the spike in gun violence across the country, and the stark partisan divide on the response to the Covid-19 pandemic, are putting public health on a collision course with politics. Although this may seem like a new phenomenon, American politics has been creating a deep fissure in the health of Americans over the past two decades.”

Tags: bmj > charlie crisp > gun violence > Haider Warraich > JAMA > joseph ladapo > medicaid expansion > Obamacare > replacement theory > Republican health policy > Roe v. Wade > Ron DeSantis > Tampa Bay News

POST-Uvalde, TX – Caring Vs. Killing.

Posted on | May 30, 2022 | Comments Off on POST-Uvalde, TX – Caring Vs. Killing.

Mike Magee

With the Uvalde, TX massacre etched in the American psyche and the smug image of Wayne LaPierre firmly emblazoned on the NRA stage this week, good-willed Americans are in search of our true center. As a physician, I recall patients whose goodness and courage and kindness brought out the best in me and my colleagues. That after all is the true privilege and reward for doctors and nurses and all health professionals – the right to care.

Collectively health professionals have a unique role in American society. Across cities and counties, rural and urban, we are asked to be available and accessible to help keep people well and respond when they are sick or injured. Those wounds come in all shapes and sizes – wounds to the body, wounds to the mind, wounds to the spirit.

As important as are our diagnostic and therapeutic interventions to society, they pale in comparison to a larger, often over-looked function. Together, collectively, we process day to day, hour after hour, the fears and worries of our people, and in performing this function, create a more stable, more secure, more accepting and more loving nation. Our jobs are made so much more difficult by politicians who support destructive policies.

Along with other Americans this week, I have struggled to accept that our nation seems willing to once again accept the sacrifice of our young, innocent children to assure an 18 year old’s right to a weapon of war. I have settled on a different set of images, and a very different narrative – a counter-point if you will – to share.

Eleven years ago, my wife and I were blessed with the arrival of our eighth and ninth grandchildren – two little girls, Charlotte and Luca. We were also introduced, for the first time as health consumers, to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). The girls came early, at 34 weeks, and struggled to work their way back up to their due date. They are about to enter Middle School, but in those early days, it wasn’t easy on them or their parents or the care teams committed to their well being.

Viewing them from my grandparent perch, the Connecticut Children’s Hospital Center NICU team at Hartford Hospital did a great job, balancing high tech with high touch, providing wisdom and reassurance, encouragement and training to the girls’ parents, who were inclusively inducted as part of the team on day one. It was really a holy thing to observe.

Politicians like Greg Abbott and Ted Cruz might want to visit a NICU without their donors. They would encounter health professionals fully capable of collaborative and humanistic care, especially when faced with a complex threats and families in crisis. They would witness:

1. Inclusion: For most humans, the first instinct when faced with trauma or threat is flight. And yet, these NICU professionals’ first instinct is inclusion. With IVs running, and still groggy from her C-section, our daughter and son-in-law were escorted to the NICU and introduced to their 3 lb. daughters. They were shown how to wash their hands carefully, how to hold the babies safely and without fear, and – while given no guarantees – experienced the transfer of confidence from the loving and capable caring professionals to them. Those were remarkable first day gifts to this young couple.

2. Knowledge: Coincident with the compassionate introduction to their daughters, there was a seamless transfer of information – each of their daughter’s current conditions, an explanation of the machines and their purposes, the potential threats that were being actively managed, and the likely chance of an excellent outcome. This knowledge – clear, concise, unvarnished, understandable – delivered softly, calmly, and compassionately, reinforced these young and fearful parents’ confidence and trust in each other, and in their care team, on whose performance their newborn daughters’ lives now depended.

3. Accessibility: The members of their care team needed to demonstrate “presence.” The outreach needed to be “personal.” This was not a rote exercise for them, not just another set of parents, not just another set of tiny babies. These were these specific parents’ precious children, their lives, their futures were now in the balance. And the performance needed to be “professional.” The team needed to be consistent and collaborative, with systems and processes in place, no descent and little variability in performance, rapid response, anticipatory diagnostics and confident timely management of issues as they arose.

As we attempt to recover once again from a senseless massacre of the tiny victims of Uvalde, from poor leadership and self-inflicted wounds, we need to be reminded that there is a beating heart and a feeling soul in America. There is a better way – holistic and inclusive, humanistic and scientific, where goodness and fairness reside side-by-side.

How might each of us actively demonstrate a commitment to inclusion, knowledge transfer and accessibility, and in doing so, assure that these latest 19 children, and all those whose senseless slaughter preceded them, were not in vain? Our politicians, on state and federal levels, need to channel a NICU professional – not a RAMBO – when they next vote on gun policy. After all, our lives depend on it.

Tags: Greg Abbott > gun violence > health care professionals > NRA > ted cruz > Texas > Uvalde

Arthur Sackler’s Ghost Has Access To Your Personal Health Data.

Posted on | May 25, 2022 | Comments Off on Arthur Sackler’s Ghost Has Access To Your Personal Health Data.

Mike Magee

When Americans first bet the nation’s health on an entrepreneurial system of care, we grossly underestimated just how far certain individuals and institutions would go in pursuing financial incentives, how benefits might be overstated and risks downplayed, and how side effects including drug addiction and lost productivity could bring a large portion of society to its knees. We also grossly underestimated just how much such a system could be gamed and, in that gaming of the system, how pivotal a player one highly determined individual might be. But in this market-driven health care system, Arthur Sackler continues to demonstrate just how wealthy one can become by advantaging patients and their diseases.

He’s been dead since 1987, but his ghost continues to access your personal health data, pushes medical consumption and over-utilization, and expands profits exponentially for data abusers well beyond his wildest dreams. Back in 1954, he and his friend and secret business partner, Bill Frohlich, were the first to realize that individual health data could be a goldmine. That relationship would still be a secret had it not been exposed in a messy family inheritance feud unleashed by his third wife after Sackler’s death.

That company, IMS Health, was taken public and listed on the NYSE on April 4, 2014, transferring $1.3 billion in stock. I’ll come back to that in a moment. But in the early years, the pair realized that the data they were collecting would multiply in value if it could be correlated with a second data set. That dataset was the AMA’s Physician Masterfile that tracked the identity and location of all physicians in America from the time they entered medical school.

Those doctors were largely unaware that they had been assigned an identifier number early in their career, or that they were being tracked, or that the AMA was profiting from the sales of their information. With this additional information, IMS information products helped inform companies commercialization plans, their pharmaceutical marketing and sales, and eventually the targeting of physicians most likely to overprescribe Oxycontin.

After Arthur Sackler’s death, the company was sliced and diced, sold and resold, merged and divested. In May 2016, IMS merged with Quintiles with ownership at 51.4% IMS and 48.6% Quintiles. The resulting company was valued at $17.6 billion and called QuintilesIMS. On November 6, 2017, it was renamed IQVIA.

Two decades earlier, Congress had passed HIPAA , designed to protect patient’s personal health information, but leaving health care organizations (not patients) in control of that data. In a compromise, those organizations were permitted to sell and mine aggregate data as long as it was detached from personal identifiers such as names, birthdates and ZIP codes.

Under the mantra of “de-identification,” the Medical-Industrial Complex went to work. One of the most successful of the lot was a West Coast start-up, MedicaLogic, which created a shared patient case database fed by thousands of doctors nationwide. The doctors were assured that the data housed in their proprietary medical record system was de-identified and intended for altruistic purposes. But its commercial worth quickly became evident resulting in a sale to GE Health in 2002, becoming the “must-have” MQIC database.

By 2013, it had been six-figure licensed to over 500 corporate clients and included focused marketing and sales insights from data mining the records of 25 million de-identified Americans over a 15 year span. Its premier customer was QuintilesIMS, now generating $4 billion in annual revenue, employing 33,000 employees and running the clinical research (largely overseas) operations for 20 of the largest pharmaceutical companies.

QuintilesIMS, now IQVIA, was the owner of MarketScan, the domicile for a 270 million Americans-strong health insurance claims repository. The original creator of MarketScan was Truven Health Analytics. IQVIA took the data from GE’s MQIC database and merged it with Truven’s MarketScan with an aim of re-identifying your health data, thus vastly expanding its commercial value. The results were alarming. As an internal GE memo later revealed, the cross reference with Tureen data allowed re-identification of the original patient source with “95% accuracy.”As one investigative report noted, “The unsettling part was how precisely the patients were flagged in another dataset, with near perfect accuracy…”

GE’s internal investigation caused some consternation in the firms legal wing, but they eventually concluded they had not technically violated HIPAA because the manipulations were one step removed from direct patient data collection. GE’s finance department was much relieved. GE’s health database and proprietary software was sold to New York private equity firm Veritas Capital, (who in the past had also bought and sold Truven) which in turn resold the entire medical records business for $17 billion on the open market.

Channeling their inner Arthur Sackler, IQVIA (formerly Quintiles, formerly IMS) justified their actions, saying they are all about improving patient outcomes by identifying what treatments work best for what diseases. What all now admit behind closed doors is that HIPAA is hopelessly outdated, and that the glaring loopholes have been identified and commercially advantaged.

In many respects, this is old news. In 1957, when Arthur Sackler appeared under oath before the Kefauver Commission in January, 1962, he lied through his teeth, denying his ownership of IMS. Now 35 years later, his ghost and the IMS progeny continue to haunt our personal health data.

What Have We Learned About Epidemics in America?

Posted on | May 16, 2022 | Comments Off on What Have We Learned About Epidemics in America?

Mike Magee

Listen to Lecture (1 hour) HERE.

Last week’s online lecture, The History of Epidemics in America, sponsored by LeMoyne College, was a great success, attended by well over one hundred registrants. The transcript of the entire lecture is available online for those interested in a relatively deep dive. But for those who are interested and time-limited, here is the content of the final two slides summarizing in 15 learnings and takeaways from six months of research.

- Epidemics, as historians have emphasized are “social, political, philosophical, medical, and above all ecological events.”

- Competing and complimentary species cycles, in pursuit of nutrition and reproduction, maintain or distort ecological balance.

- Populations initially respond to epidemics with fear and flight. Scapegoating and societal turmoil are common features. Diseases disadvantage the poor, the weak, and those without immunity or prior exposure.

- Epidemics often travel side by side with warfare in transmitting and carrying microbes, and exposing vulnerable populations. Historically, epidemics have repeatedly played a role in determining the ultimate outcomes of warfare and conflict.

- Throughout history, scientific advances have – by enabling travel, congregation, and entry into virgin territory – triggered epidemics, but also provided the knowledge and tools to combat epidemics.

- Domestication and sharing of animals has enhanced the introduction of microbes to populations vulnerable to epidemic disease.

- Disease, accompanied by aggression, has been the major factor in the destruction of native cultures and has decimated native populations in the Americas.

- Slavery was in large part a response to workforce demands created by the epidemic eradication of native populations intended to serve as indentured servants on large agricultural plantations that raised and exported highly lucrative products into Old World markets.

- Epidemics often result in secondary consequences. For example, Yellow Fever and the defeat of the French in Saint-Domingue led to Napoleon’s divestment of the Louisiana Territory. Struggles to control and explain the Yellow Fever outbreak in Philadelphia in 1793 helped define the emergence of two very different branches of American Medicine over the next century.

- Scientists defining “germ theory” and social engineers leading the “sanitary movement” reinforced each other’s efforts to lessen urban centers vulnerability to epidemics.

- Immunization has a long and controversial history. As enlightened public policy, it has saved countless lives. It can, as illustrated by Justice John Marshall Harlan’s 1905 decision in Jacobson v. Massachusetts, create uncomfortable legal precedents and unintended consequences as in Justice Oliver Wendall Holmes 1927 decision in Buck v. Bell.

- The U.S. scientific community prematurely declared victory over communicable diseases in the early 1960’s.

- In the wake of HIV/AIDS, some scientific leaders actively warned of ongoing population wide vulnerabilities beginning in 1992.

- Genetic reverse engineering technologies empowering “gain-of-function” led to Consensus Statements in 2014 of potential disastrous consequences, and epidemics that would be difficult to control. High speed travel, climate change, warfare induced human migration, and dysfunctional health care systems make epidemics more likely in the future.

- The U.S. Health Care System in initial Presidential leadership, strategic operation, mitigation, and delivery of acute services failed on a large scale when confronted with the Covid-19 pandemic. Many of the over 1 million U.S. casualties were preventable.