Canada vs. U.S. Health Care: Comparative Analysis in 2017

PDF File Available for Download (Print Friendly)

Canada vs. U.S. Health Care: Lessons Learned – 2017.

Mike Magee M.D. (©HealthCommentary.org 2017)

America’s attention is once again on health reform. Even as Republican governors preach caution, the Republican controlled Congress continues to vow to repeal the Affordable Care Act and turn Medicaid into block grants.

I. Historical Perspective

The U.S. doesn’t exactly have a great track record when it comes to health policy decisions. Compared to Canada, we’ve consistently chosen “free enterprise” approaches that have been singularly disappointing in performance. Scientific progress has become unlinked from human progress. And the Medical-Industrial Complex continues to grow in size and appetite, while health outcomes and value for the dollar are hard to come by.

What can we learn in 2017 by taking close look at the Canadian health care system? We begin with an analysis of critical decisions at four moments in history – 1947, 1957, 1964, and 1984.

In 1947, in the wake of WW II, the Canadian Province of Saskatchewan launched the first provincial universal public hospital insurance plan. South of the border, the U.S. chose a very different path. With inducements in the tax code, and exemption from war time wage and salary controls, our government encouraged private employers to provide their workers with health insurance as part of what would become a standard benefit package.

A decade later in 1957, Canada passed the Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act which provided 50/50 cost sharing between the federal government and any of 13 provinces and territories that chose to participate in universal coverage of their respective populations. In the U.S. employer based insurance had now been extended to nearly 70% of Americans, pharmaceutical profiteers were being lined up for interrogation by Senator Kefauver’s Commission, and the AMA was mapping out its strategy to defeat “socialized medicine”.

In 1964, against the opposition of the Canadian Medical Society, Canada’s Royal Commission on Health Services, recommended and soon succeeded in launching a comprehensive and universal national health program. The program, called Medicare, covered everyone but not everything (pharmaceuticals, eyeglasses, dental care, and home care were exempted). They did however include federal planning and standards to promote and maintain optimal preventive health of all Canadians. A federal governance body was in charge of standards, but the delivery of care was strictly delegated to the provinces and territories which themselves managed and prioritized annual budgets, and designed their own governance systems.

In the U.S. at the same time, President Johnson in the wake of President Kennedy’s assassination, and with some skillful maneuvering by veteran legislator Wilbur Mills, passed our own Medicare, a universal program as well, but only for citizens over 65. It was federally funded and federally directed, having proven a few years earlier that voluntary enrollment programs controlled by individual states would fail. They also passed Medicaid, which like the Canadian program included a mix of federal and state funding, and delegation of responsibility for care delivery to the states. Standard setting was weak in Medicaid, and wide variability became immediately apparent both in the definition of who qualified, what was covered, and the level of each states financial commitment to services.

The Canadian government at the time held tightly to the principle of universality and public funding with federal and territorial governments contributing. All Canadians were covered for roughly 70% of services, and the national government itself (not private insurers) was the singe administrator and payer of these covered services. This decision was grounded in the philosophy that Canada’s success ultimately depended on the health of Canadians, that this health was a human right, and that excessive administration would drive up cost and complexity, placing an undue burden on their citizens.

Fee schedules were standard across each province’s geography and population, and negotiations with doctors and hospitals in each province or territory, as part of the budget setting process, allowed for prioritization and full transparency. Providers submitted bills for services. Government paid the bills. And the patient was left alone.

The U.S. chose an opposite course. With full faith in capitalism and competition, they reasoned that inclusion of private insurance companies, who were already deeply entrenched in their employer based health insurance system, would through competition with each other hold costs in check. U.S. doctors as well billed fees for services, but there were no annual budgets, highly variable rules and coverage, and remarkable complexity and variability that confused everyone. It also didn’t hold down costs, as insurers, responding to their shareholders managed to remove at their peak 25 cents on the dollar for their services.

In 1984, as part of their national commitment to continuous thoughtful evolution, the Canadian government passed the Canada Health Act which combined their hospital and medical acts and refined and reinforced their administration of the program as well as four anchoring pillars – portability, accessibility, universality and comprehensiveness. The deliberations were out in the open and fully transparent.

In 1984, with U.S. health care costs careening out of control, and an AIDS epidemic gaining steam absent government leadership, the U.S. once again placed all her cards on “private enterprise”. Four years earlier, in the waning days of a one-term presidency mired in recession, President Carter had reluctantly signed the Bayh-Dole Act. The legislation released 26,000 federal patents (derived from federally funded research) for private use by industry and academic health centers. The scientific progress unleashed was undeniable, but the loss of checks and balances and the realignment of values and power within premier academic health centers uncoupled entrepreneurship and scientific progress from human progress. An unholy alliance at the center of a medical-industrial complex had been consummated.

II. Canadian Health Care: Facts and Fiction.

During the Hillary Clinton health care debate of the 1990’s, our approach to health care delivery was compared to multiple other nations – including Canada. Supporters of our status quo worked hard to emphasize other nations differences and weaknesses.

The criticism of Canada, which even then was registering demonstrably better outcomes at a fraction of our cost, was twofold. First our health leaders accused the Canadians of rationing services and delaying life-saving treatments. And second, they claimed that our neighbors were able to get away with this because we were on their southern border, and Canadians in large numbers emigrated to our institutions to get access to services denied by their own niggardly system. Additionally we claimed that Canadian doctors were so dissatisfied with their system that they were routinely relocating to the U.S. to practice medicine.

These paired and interdependent false realities were presented with such certainty, and reinforced by our own medical elites so consistently, that physicians bought into the propaganda without critically examining the facts. It was a full decade before these false claims were analyzed in earnest. In 2002, four health policy experts, with the support of the Canadian Medical Council, which had renamed itself the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, established unequivocally that the claims of medical migration, by either patients or their doctors, were bogus.

The Health Affairs publication, titled “Phantoms in the Snow: Canadians’ Use of Health Care Services in the United States”, didn’t mince words. Backed up with an array of facts and figures, and exhaustive documentation, the authors stated, “Results from these sources do not support the widespread perception that Canadian residents seek care extensively in the United States. Indeed, the numbers found are so small as to be barely detectible relative to the use of care by Canadians at home.”

On the Canadian side, only 90 of 18,000 citizens surveyed had used American services, and the vast majority of these were tourists seeking emergency care while traveling. Surveys of major U.S. academic centers, including those in border states reinforced the same conclusion: few if any Canadians. In the end, the authors concluded, “The numbers of true medical refugees—Canadians coming south with their own money to purchase U.S. health care—appear to be handfuls rather than hordes.” The same held true for Canadian doctors who had little to no interest in relocating.

Concurrent studies did reveal that Canadian waits for certain elective procedures and access to high tech diagnostics were longer than in the U.S. This fully transparent trade-off, made by provincial and territorial health governing bodies, was largely supported by Canadians as necessary and responsible budget management of priorities. They never hid the fact, but rather raised it in the public square. And recent corrective measures have not been entirely successful. (Message: Canada’s health care system does continue to have its own challenges.)

Absent proof of an escape valve migration south, U.S. detractors continued to wave the bloody flag of rationing, even as studies of our own system revealed that our population is more likely than citizens from other developed nations to put off needed treatment because they can’t afford it – de-facto financial self-rationing if you will.

In 2003, the U.S. under President George W. Bush continued to struggle to control health care costs. The nation’s response, with the opaque support of PhARMA, the AMA and AAMC, and the hospital and insurance industries, was to approve Medicare Part D’s non-negotiable coverage of pharmaceuticals for seniors at prices roughly 150% of the cost of Canadian counterparts.

Gallup polls at the time found that 57% of Canadians were “very” or “somewhat” satisfied with their health care system compared to 25% of Americans. 44% of our citizens were “very dissatisfied” while only 17% of Canadians felt the same. Part of the reason for relative calm up north was that their system was continuing to evolve in the full light of day. What were they up to?

In 2004, Canada’s Prime Minister and the provincial and territorial leaders announced “A 10-Year Plan to Strengthen Health Care”. Their opening statement? “As a nation, we aspire to a Canada in which every person is as healthy as they can be-physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually.”

Their guiding principles don’t sound like ours – no words like innovation, entrepreneurship, precision health or highly leveraged technologic wonders; no battles for ever increasing research funding by competing diseases; no academic goliaths with million dollar CEO’s overseeing patent producing enterprises as patient care takes a back seat.

III. Scorecard.

In 2007, the Cambridge based National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), self-defined as “the nation’s leading nonprofit economic research organization”, produced a singularly myopic white paper comparing the U.S. and Canadian health care systems. Noting that Canada is a “single-payer and mostly publicly-funded system” while the U.S. is a “multi-payer, heavily private system”, NBER stated “Much of the appeal of the Canadian system is that it seems to do more for less.”

At the time of the paper, Canada was devoting about 10% of its GDP to health care versus 16% in the U.S. While spending less, Canada managed a significantly lower infant mortality rate, and higher life expectancy. The authors attempted to explain these negative findings by first noting that low birth weight is associated with high infant mortality, and then offering this analysis, “Low birth weight-a phenomenon known to be related to substance abuse and smoking-is more common in the U.S. For babies in the same birth weight range, infant mortality rates in the two countries are similar. In fact, if Canada had the same proportion of low birth weight babies as the U.S., the authors project that it would have a slightly higher infant mortality rate.”

Moving next to the troublesome issue of life expectancy, they declared, “The gap in life expectancy among young adults is mostly explained by the higher rate of mortality in the U.S. from accidents and homicides. At older ages much of the gap is due to a higher rate of heart disease-related mortality in the U.S. While this could be related to better treatment of heart disease in Canada, factors such as the U.S.’s higher obesity rate (33 percent of U.S. women are obese, vs. 19 percent in Canada) surely play a role.”

That the NBER economists could present such arguments with a straight face well illustrates the remarkable disconnect between cause and effect, prevention and intervention, and scientific progress versus human progress in the U.S. health care system and its Medical-Industrial Complex. Eight years later Canada would boast a life expectancy of 82.2 years and an infant mortality rate of 4.9/1000 live births versus U.S. numbers of 79.3 years and 6.5/1000 live births. It should be noted as well that the per capita health care expenditure in Canada at the time was $5,292 compared to $9,403 in the U.S.

At the same time as the privately and opaquely funded NBER economists were penning their insights, actual public health leaders in Canada, after two years of thought and debate in the public square on a vision that would govern Canadian health care into the future, released its’ “ten year plan”. It included these five principles:

1)”Prevention is a priority. Canadians value their health.

2) They prefer to live a long life in good health while preventing disease or injury, rather than experiencing severe illness and the pain, suffering and loss of income that they can cause; they also want to avoid premature death.

3) Promoting good health just makes sense. While we have the means to prevent or delay many health problems, Canada’s current health system is mainly focused on diagnosis, treatment and care.

4) To create healthier populations, and to sustain our publicly funded health system, a better balance between prevention and treatment must be achieved.

5) Prevention is a hallmark of a quality health system. Internationally, health promotion and prevention are recognized as essential pieces of high-quality health systems.”

In a remarkably insightful summary, Canada’s national, provincial and territorial public health leaders declared:

“Health promotion is everyone’s business. While it is clear that health services are a determinant of health, they are just one among many. Others include:

1) environmental, social and economic conditions;

2) access to education;

3) the quality of the places where people live, learn, work and play;

4) and community resilience and capacity.

Because many of these determinants of health lie outside the reach of the health sector, many of the actions to improve health also lie outside the health sector, both within and beyond government. This means that many government departments and a wide range of people and organizations in communities and across society play a role in creating the conditions for good health that support individuals in adopting healthy lifestyles. Promoting health and preventing diseases is everyone’s business—individual Canadians, all levels of government, communities, researchers, the non-profit sector and the private sector each have a role to play.”

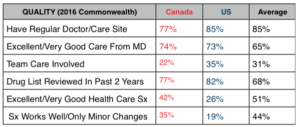

This is not to say that the Canadian health care system is perfect. Far from it. The Commonwealth Fund in 2016 compared performance of 11 developed nations on measures of quality, cost, access and communication. The charts below are derived from that survey and compare Canada, the U.S., and the average of all 11 nations.

On Quality: The U.S. compares favo rably on having a regular doctor, receiving good care, and having patients’ drug lists reviewed. We are also a bit ahead of Canada in team care since they rely more heavily on private fee-for -service doctors. But when patients assess whether our system as a whole is optimal and whether it works well and needs only minor changes, it is clear our citizens lack confidence compared to the Canadians, and that the Canadians trail the national average.

rably on having a regular doctor, receiving good care, and having patients’ drug lists reviewed. We are also a bit ahead of Canada in team care since they rely more heavily on private fee-for -service doctors. But when patients assess whether our system as a whole is optimal and whether it works well and needs only minor changes, it is clear our citizens lack confidence compared to the Canadians, and that the Canadians trail the national average.

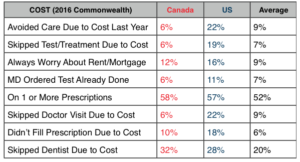

On Cost: The Canadian system does not cover dentists, eyeglasses or pharmaceuticals. If citizens want coverage for these they must purchase a private plan. Even so, the chart above clearly illustrates that U.S. citizens by significant margins feel greater financial stress than their neighbors to the north and purposefully ration their own care by avoiding necessary but expensive treatment.

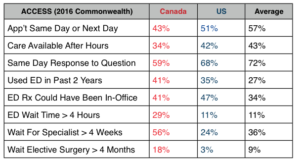

On Access: On nearly every measure, Canadians score worse on access to care than do the Americans. These are issues they have focused on for over a decade and not resolved. The waits are concentrated in the area of elective surgery and specialty referral. They have the same number of doctors per 100,000 as do Americans but have not added physician extenders and team approaches to the degree the U.S. has. Instead, they have fallen back on ED visits in the off hours, which are free, resulting in long waits after hours.

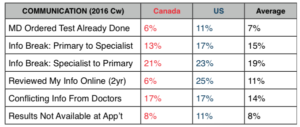

On Communications: The results are mixed. Canadians lag in their use of online medical records though the U.S. has a long way to go as well. The American system shows the signs of excessive complexity with more repeat and unnecessary tests, more breakdowns in communication between generalists and specialists, and information unavailable at the time of appointment.

On Communications: The results are mixed. Canadians lag in their use of online medical records though the U.S. has a long way to go as well. The American system shows the signs of excessive complexity with more repeat and unnecessary tests, more breakdowns in communication between generalists and specialists, and information unavailable at the time of appointment.

By moving toward universal care, adjusting our payment incentives, inserting performance bonuses to coax quality measures and electronic medical records, President Obama was heading in the right direction. But the Republicans seem determined to roll back the clock, insert even greater complexity, and place a greater burden on vulnerable populations who’s greatest need is simplicity and clarity.

IV. A Challenge of Culture.

In the 2008 classic movie, A Few Good Men, Jack Nicholson explodes under the relentless pressure of prosecutor Tom Cruise, and yells “You can’t handle the truth!” A careful critical examiner of the US health care dilemma in 2017, in the shadow of our neighbor to the north, might easily draw the same conclusion.

As the new Millennium approached and our health care costs escalated out of control, uninsured numbers rose and performance lagged, leaders expended energy defending our system as “the best health care in the world”, and defamed the Canadians and others with unsubstantiated claims that they were piggy-backing on our system to cover their own weaknesses.

In contrast to our own penchant for opaqueness, complexity and tolerance of conflict of interest, the Canadians – while far from perfect – have attempted to continuously and responsibly evolve their system and have transparently exposed their strengths and weaknesses to the light of day. As a result, Canadians support their system in far greater proportions that do the Americans.

The fact that Trump and the Republican Congress have no real plan beyond repealing Obamacare, or that the Democrats and President Obama did not manage perfection while facing constant and relentless opposition over eight years, could lead many to believe that this whole mess is just too complicated to understand let alone fix.

But the pathway out, on the surface, is pretty clear. Everyone needs to be covered to share risk. The administration of health coverage and a citizen’s choices need to be simple and clear so that the general public can understand and participate. Elements that add cost but not value must be eliminated. And accountability must be anchored by a strategic long term plan, committed national and regional leadership, and a vision and value proposition.

What is increasingly apparent, and the truth we refuse to acknowledge, is that the problem is not the system specifically, but rather our culture and values that have been hijacked. Beginning just after WWII, but accelerating in the 1970’s and 1980’s, cross-sector leaders in energy, finance, health care and the military coordinated a deliberate attempt to seize control of power in industry, non-profits and government in pursuit of career advancement, profits, and power. These “complexes” focused on dismantling checks and balances, and managed, in a twisted dialogue among themselves, to simultaneously chase government subsidies while excoriating government intervention.

As multi-nationals expanded so did large profit chasing, entrepreneurial “non-profits” who diligently avoided taxes while aiding and abetting the rapid expansion of poverty and income disparity. Between 1960 and 2015, “non-profits” percentage of the GDP grew three fold with 1.6 million “non-profits” now employing 10% of all American workers.

As boundaries blurred, associations of associations evolved to allow coordination of government relation’s strategies. Attendants at their conventions were multi-sector true believers in the free-market and profits. Their cover? The claim that entrepreneurial zeal and imagineering would, through discovery, solve all of America’s problems. And those problems were growing at an alarming rate, fueled by organizations like the U.S. Chamber of Congress that spent over $1 billion lobbying in the past decade.

With President Reagan in power, enabling legislation opened the floodgates. New laws, like the 1980 Bayh-Dole Act, actively incentivized government-industry-academic non-profit collusion. In its wake, community needs faded as corporations became persons and free speech morphed into free spending. This was an opaque and deliberate hostile takeover, executed by experts with patience and near unlimited resources. Bill Moyer’s notion of “public action for public good” became a quaint euphemism for old-fashioned, out-of-touch PBS dreamers.

What felt like progress was finally revealed for what it was in the 2008 financial crisis. But this near societal collapse at the hands of free-market zealots surprisingly only tightened the embrace between the state and the private sector. The 2010 Citizen United and 2014 McCutcheon decisions solidified an American world of opaque complexes, integrated cross-sector, conflicted and cooperative power elite who continued to shift the distribution of wealth to their own kind as everyday Americans became more and more disillusioned.

So the truth we can’t handle is that, unlike Canada, we have let our highest ideals slip away from us, and we’re not quite sure how to right this ship. And yet, until we acknowledge that truth, we can’t address U.S. health care that now encompasses nearly 1/5 of our economy.

This is a nation where business and government are now largely indistinguishable from one another. This is a nation where checks and balances have melted in the face of a half-century of deliberate assault creating a world absent countervailing self-correcting instincts. This is a world that for the chosen few celebrates individualism in the extreme and survival of the financially fittest, an environment where free-market ideologies routinely fail us, but then are re-subsidized and reinforced and recast by compromised insiders.

Under these conditions, we should not be surprised that the Trump administration and Congressional Republicans are now presenting health policy solutions that would increase complexity, further burden the poor and disadvantaged, and add cost at every turn.

As one commentator concluded, “Today health care in America is dominated by the medical-industrial complex…a mix of intimately interacting for-profit businesses, non-profit enterprises, and government agencies…every part of it is completely dependent on government spending and completely integrated with public-sector institutions and programs. Huge non-profit enterprises play a central role not just in the actual administration of health services but also in the generation of profits for the for-profit sector…the American health care system is both built on and reinforces an individualistic, free market ideology that simultaneous embraces government subsidization and scorns government intervention.”

Further tinkering with our broken health care system will almost certainly add cost and undermine quality and coverage. To begin to define a way back home, we need to initially focus on two fundamental challenges.

Problem 1: Defining a National Health Care Vision:

There is an actual “American Dream”. The phrase is attributed to New England social historian and writer James Truslow Adams. In 1931, he wrote The Epic of America in which he described “a dream of a social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable, and be recognized by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position.”

When Canada embarked on developing its national health care system in 1947, they identified the most knowledgeable and respected leaders they could find on the national, provincial, and territorial stages, and empowered them to create a mission and vision for Canadian health care.

Their output, reaffirmed in 2005, mirrored Adams vision. It said, in part, “As a nation, we aspire to a Canada in which every person is as healthy as they can be—physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually.”

They defined a healthy nation as “one in which all Canadians experience the conditions that support the attainment of good health. The strategy identifies two goals: improved overall health and reduced health disparities.”

The U.S. skipped this critical strategic planning step and has been paying the price every since. Our government needs to appoint a representative body and charge them to create a consensus national vision and guiding principles for our nation’s health.

Problem 2: Disentangling the Medical Industrial Complex:

Seeing the premier academic medical institutions to the south veering off into speculative entrepreneurism, patent seeking, and fortune hunting, Canadian health leaders took the time to define the social accountability responsibilities of their medical schools. The set of principles linked the schools to the national health care system and stated in part that:

“Medical schools respond to the changing needs of the community by developing formal mechanisms to maintain awareness of these needs and advocate for them to be met”, and “Medical schools work together and in partnership with their affiliated health care organizations, the community, other professional groups, policy makers and governments to develop a shared vision of an evolving and sustainable health care system for the future.” In contrast, America’s premier academic health care systems chased the golden patent ring and research discovery laden profitability, leaving patient care and medical education in the wake.

Our “system” began as a series of self-interested professional guilds, industries, hospitals, insurers and government agencies that together formed a messy, unruly aggressive complex. For a time their conflicts with each other created some element of informal checks and balances on the system. But in the past half century, the major players in the sector infiltrated the government, and cross-fertilized each other to the point that they realized it was better and more profitable in the long run to collude behind closed doors than to fight with each other out in the open. Cooperating as an invisible united front, they now maintain control of policy, legislation and future profitability.

V. Common Wealth

Piecemeal attempts by reformers have been easily repulsed. In 2008, Don Berwick acknowledged an absolute need for universal coverage and for organizational leadership. He called his leader an “integrator” who’s roles included guiding individual and family partnerships, primary care network building, population health, finances, and macro system integration. But compared to the Canadians, his faith in prevention versus carefully re-engineered high-tech intervention was qualified. His words: “Good preventive care may take years to yield returns in cost or population health.”

At around the same time Mayo Clinic’s CEO Denis Cortese, now director of Health Care Delivery and Policy at Arizona State University, endorsed “a U.S. Health Board modeled after the Federal Reserve Board… An independent board made up of providers, payers, and patients could focus on the complex decision making that must be insulated from the politics of Capitol Hill.” Yet, as we see today, politics remain front and center.

A few years earlier, two former NEJM editors offered their prescriptions for change inside the Medical-Industrial Complex. In 2004, Marcia Angell zeroed in appropriately on the pharmaceutical industry defining “how they deceive us and what to do about it”. But she appeared to deliberately leave academic medicine’s culpability unaddressed. A year later, Jerome Kassirer filled in the dots, focusing on “how medicine’s complicity with big business can endanger your health”.

He correctly concluded, “Like-minded people with ‘unique’ knowledge may have similarities of thought and come up with a uniform conclusion that is biased (or even completely wrong)”. Lending a term from the military, he highlighted “incestuous amplification” and recommended that, when filling governmental medical science advisory boards, the nation “save such ‘prizes’ for those with no financial ties, that is, to reward people who stay free of personal financial entanglements with industry.”

This is not the place, nor is there adequate space here to address how best to disentangle co-conspirators from industry, academic medicine and government. I will only say that where there is a will there’s a way – many ways.

President Obama realized, in looking for a starting point, that Governor Romney was on the right track in Massachusetts in 2006. Republican or not, the governor realized there had to be a plan; leaders had to held accountable; all citizens had to have mandated coverage because history had proven more than once they would not do so voluntarily. Channeling the spirit of our northern neighbors, Romney ally, Democratic Speaker of the House (MA), Sal DiMasi, spoke truth to power. “It was supposed to be a community of people where laws were made for the common wealth. That’s why we became a ‘commonwealth’. Nobody in Massachusetts will ever be turned away for health care”.

VI. Federal Governance:

As we have seen, America’s health care system – disintegrated, opaque and heavily conflicted – didn’t just happen. It is the result of thousands of conscious decisions over nearly a century. Choices made have tipped the scale toward intervention, technology, and medicalization at every turn. Peggy Noonan recently suggested that Paul Ryan’s bill will likely hyper-accelerate income disparity that she highlights as the most pressing threat to American democracy. Granted, that’s depressing.

But strangely enough and contrary to prevailing views, there are three reasons. The first is that we already expend more resources than necessary to lead the world in health performance. The silver lining of our remarkably inefficient delivery system is that we need not raise additional funds but simply reallocate them. After all, we expend just under $3 trillion a year on health care.

The second encouraging finding is that the pathway to solutions involves less complexity, not more. This is primarily an exercise in governance and editing. Our comparison with Canada reveals obvious course corrections that, until now, we have avoided. We currently lack a concise, long-term plan for a healthy America.

Finally, the MIC’s power and influence derives from secret collusion, limited checks and balances, and an integrated career ladder, all of which are amenable to policy corrections. Segregating research/discoveries from education and patient care will take us 90% of the way. Transparency and appropriate independent checks and balances should do the rest.

So let’s take a critical look at our current organizational assets – first national with state to follow.

Guilds and Unions:

Our nation is rich in guilds and unions that represent segments of our health care sector. They are interested foremost in advocating for their members financial needs and privileges. And there is nothing wrong with that. Foremost among the group are the AMA, ANA, AHA, PhRMA, AHIP and their distributive federation members. Add to these players multi-focused organizations like the AAMC which sees itself as the champion of post-Flexner quality medical education, but has yielded considerable high ground to its own Council on Teaching Hospitals and Health Systems which primarily seeks federal research and education dollars with few strings attached. Then there are the historic non-profits like the American Cancer Society and the American Heart Association, and the more recent collection of industry funded advocacy organizations.

These bodies need to play a critical participatory role in the provision of care. But it is important to recognize that they are neither independent nor an adequate substitute for an official national body to guide our health care future.

Governmental Entities:

America has a range of governmental bodies that have developed and evolved over the past half century. In general, they lack clarity, focus and long-term visions, and have long ago lost their independence. Rather than being planned deliberately, these bodies have “happened”, usually in response to crisis or politics.

FDA:

The FDA’s three major evolutions – the 1906 Food and Drug Act, the 1938 Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, and the 1962 Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendments – were all in response to tragedies, namely tetanus-laced vaccines, childhood deaths from antifreeze tainted sulfonamide elixir, and thalidomide.

In the mid 20th century, free-marketers used “Red” baiting” and the Soviet Sputnik lead in space to bolster charges of a U.S. “drug lag”, and to justify green-lighting new drugs to the market. The late 1970’s recession offered another opening for industry intrusion. Today that push is on again, and yielding the same questionable results – for example, the use of “golden vouchers” to push generics with stratospheric prices. Through it all, the creation of new “diseases” and intrusive professional marketing of cures for these maladies has reinforced physicians and patients addiction to drugs and quick fixes.

NIH:

The same players who have infiltrated the FDA do double time on Advisory Committees and Foundations at the NIH. The NIH, strangely enough, owes its odd existence as a conglomerate of “Institutes” to two middle-aged women philanthropists, Mary Lasker and Florence Mahoney who with the help of their fabulously wealthy PR/Media magnate husbands first staged a takeover of the American Cancer Society in the late ‘40’s, replacing its doctor Board members with New York City businessmen, and then pushed through an unprecedented federal infusion of cash into “research institutes” whose purposes matched their own parochial interests.

To pull off this feat, they engaged academicians, who in later decades would be called “thought leaders”. As the NIH grew, it remained true to form – medicalized and specialized – a career escalator.

Today you will find descendants of Mary and Florence on NIH Boards, funding colloquia, and attending government/industry/academia galas hosted by Research America! and Friends of Cancer Research. Genomics, Precision Medicine, and yet another “War on Cancer” are today’s darlings – again, fine. But from a national health governance standpoint, it would be a huge mistake to confuse scientific progress with human progress.

HHS:

And then there is the Health and Human Services Department or HHS. Way back in 1798, our early leaders were worried about sick and disabled seamen. They passed an act and funded their care. That was the early beginnings of what became the U.S. Public Health Service. A half century later, President Lincoln launched the Bureau of Chemistry within the powerful Agriculture Department. As the new century approached, the focus was on immigrants and communicable diseases. We had the National Quarantine Act of 1878 and a one room research lab set up on Staten Island a decade later.

The Flexner medical education reforms would come and go before the single “National Institute of Health” name was placed on the Public Health Service’s Hygienic Laboratory in 1930. In the middle of the Great Depression in 1935, we passed the Social Security Act, and a decade later created the CDC. By 1953, it seemed time to consolidate. So Eisenhower created the Cabinet-level Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) Department.

When a separate Department of Education was created in 1980, HEW became the Department of Health and Human Services. By then we had Head Start, Medicare, Medicaid, funding formulas for medical education, Community Health Programs, the National Health Services Corps, a National Cancer Act, and a Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) to manage Medicare and Medicaid separate from Social Security. After that came AIDS, DRG’s, HMO’s, Organ Transplantation, Health Care Policy and Research (now AHRQ), Ryan White, Nutritional Labeling, the Human Genome Project, HIPAA, SCHIP, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (instead of HCFA), Medicare Part D…and on and on.

So you see what I mean. Canada planned its health system. Our’s just happened. Our major bodies now under HHS include the FDA, NIH, and CDC. They are non-transparent, MIC infiltrated, expansive, expensive enterprises. They scream for editing and focus.

Shuffling The Deck:

FDA needs to drop the gimmicks, focus on risk/benefit, and eliminate from its advisory and evaluative bodies any individuals with financial conflicts. Period. Do your job. Make sure our drugs are safe and effective. You are not an agent of industry. Attention Scott Gottlieb: Nowhere in your job description does it say “Make the American pharmaceutical, biotech and medical device industries great again!”

CDC needs to admit that there is more to creating a preventive health care system than adding an initial to your name. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is good at infectious disease, food borne pathogens, environmental health, occupational safety and health. Their Epidemic Intelligence Service is the best in the world. But agents in the transformation of U.S. health delivery from intervention to prevention, they are not. Programs like “winnable battles” which focuses on a few issues like obesity feel like add-on’s at best, and have yielded spotty results. Better to split off Prevention, bump it up, and give it some real resources and status.

NIH needs to own its “for-profit” status. You have become a national gold mine for innovative, transformational medical science and entrepreneurial marketable ideas. And that’s just fine. We gave you Bayh-Dole and along with collaborators in industry and academic medicine, you’ve mined it brilliantly. Keep up the good work!

But from now on your grants can only go to “for-profit” arms of the non-profits and will be taxable. That’s only fair since the recipients get to keep the profits and patents derived. Let’s be transparent here, and call your multi-sector collaboration what it is now – an engine of American industry. As speculative scientists, don’t complain that our checks and balances to protect the public from over steps in pursuit of fame and fortune will treat you as business rather than health professionals.

With those new rules, we’ll trust that at least some of the valuable scientific progress you uncover will lead to broad human progress. Also, stop asking for more and more money. Your partners in the “for-profit” arms of academic medical centers and industry can help your budgeting and prioritizing better than the descendants of Mary Lasker.

HHS? You need to proceed on two fronts if the U.S. is to reach its’ health delivery potential. First, re-focus and re-form the CDC, NIH, and FDA as I’ve suggested above. Second, create a consensus national vision and guiding principles for our nation’s health, and appropriately organize and resource prevention. In this regard, Health Canada (their version of HHS), has a piece titled “Health Canada – a partner in health for all Canadians” that should be required reading.

VII: State Governance.

One of the most enduring myths that we Americans support when it comes to Canadian health care is that it is a nationally run, monolithic offering with little variability. That is patently false.

In fact, Canada’s official beginnings in health governance began in the province of Saskatchewan in 1946. For several decades they had been struggling to improve access to medical care, and then took their learnings and passed the Saskatchewan Hospitalization Act that provided universal coverage for hospital care to its citizens. Four years later, the province of Alberta followed suit with a public health plan that eventually covered medical services for 90% of its population.

In 1957, the national government upped the ante by offering to cover 50% of the cost of health care to provinces and territories that embraced their Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act, which eventually formed the pillars of the current Canada Health Act. By 1961, all ten provinces were aboard, and surprisingly controlled their own budgeting, priority setting, licensing, and provider participation within their territories. The national government set the mission and vision and agreed to pay part of the bill as well as administer the insurance details of the program. But the provinces did the rest.

In doing so, Canada traded control and systematic predictability for local support, involvement, and sustainability. What happened over the next few decades in terms of cost sharing, governance and variability well informs the current raging debate over replacement of Obamacare, and especially the fate of Medicaid in the U.S.

First the finances. To begin with, Canada never agreed to pay the entire health care bill for its citizens. In fact, national and provincial governments pay about 70% of the bill, and coverage is excluded for pharmaceuticals (although nationally negotiated pricing puts their cost at roughly ½ to 2/3 of ours), dentistry, and optometry. The remaining 30% falls on Canadian’s shoulders, covered either by private supplemental plans or out of pocket.

Of the portion the government does pay, the original deal was that this would be a 50/50 split. But as in the U.S. after the institution of Medicare and Medicaid, costs rapidly escalated. Within a few years, the national government retreated to block grants, making these a line item in their budget. In the years that followed they first trimmed this line by 5% and later by 30%. The net effect was to alter the 50/50 bargain to 30/70, and finally to 15/85 today.

The individual provinces and territories then primarily control the decisions and most of the cost burden of their programs. There is considerable variability. In cost for example, Alberta pays roughly 20% more per capita than Quebec. In governance, some use province wide boards, and others rely on local hospital boards. And in outcomes, performance varies widely. Such is the price of a distributive system.

What is uniform is that all Canadians have coverage of the 70%, and this is provided through a single insurance plan administered by Canada itself. By doing this, Canada reinforces a national vision and basic access to services for all its citizens. As important, it eliminates some of the cost shifting and payer-mix selection problems that have plagued the U.S. private insurer based model from the beginning. Stated plainly, we need charity care because: 1) Someone doesn’t have insurance, or/and 2) Someone has lousy insurance, or/and 3) doctors and hospital leave the poor and vulnerable in the lurch.

When President Obama chose the course he chose for the ACA, and Governor Romney chose the course he chose for Massachusetts, both were following, in part, the Canadian playbook. The starting point for both was, as in Saskatchewan, coverage. Broad participation by all would be necessary. The costs of the old and sick, needed to be counter-balanced by the contributions of the young and well. Both chose to use carrots and sticks to empower their mandates.

Massachusetts had the opportunity to adjust and fine-tune theirs. Obama, in the face of 8 years of determined and relentless opposition to kill his signature program, was never afforded the same opportunity. Specifically, 19 states not only didn’t stay neutral, they went nuclear. Many sat on their hands rather than work on state exchanges. 19 refused what became a 100/0 deal to cover cost of expansion of Medicaid. Remarkably, 20 million Americans still participated. Both legs of the program, as in Canada, embraced local control, and were provided a relatively free hand. For example, appeals for experimental models, as with Arkansas’s use of private insurers for Medicaid, were given a green light and proved successful, in part because it shielded and protected their poor and vulnerable citizens from discrimination by local providers.

But that was then and this is now. Paul Ryan’s plan, including caps on Medicaid, has run into stiff Republican head wins. This is not because the CBO (which they preemptively undermined) believes 24 million will ultimately be uncovered as they once again arrive in desperation on ED doorsteps across the nation (the good old days.) Rather its because analysts, with near uniformity, are predicting disaster – especially for the rural and elderly poor who figured prominently in their own and Trump’s election.

So what should we do?

As in Canada, we need to embrace local support, involvement, and sustainability. That means dealing the states in, but remaining united.

We do need a mandate. All citizens must contribute up to their means. This means fine-tuning the incentives so that people, especially young people, act.

We also need to help fund our health programs with graduated taxes on our most wealthy. Income disparity is now the greatest threat to our democracy. Supporting national health helps spread the wealth in more ways then one.

We need to build on the Medicaid success, and continue to support state waivers in the interest of openness and experimentation.

We should not move to block grants. That just passes the buck. Instead let’s work with state leaders to incentivize the creation of compassionate financial brakes on the system. We are all in this together, and we’ve proven that some states, if left in the darkness, will tolerate great suffering of their people rather than share resources or responsibility.

We need to be confident that many of the 19 state hold-outs will now choose to participate. If they do not, we need a back-up plan that does not depend on the largess of private insurers.

We need to call the private insurers bluff. They want to get out of the business. Fine. Get our best national and state public health financial people on the first plane to Canada, and figure out what they did to make Canada the top payer. If our private insurers wilt, we will have gained resources not lost them.

The U.S. health care system is at a turning point. On that we can all agree. Our problem is not lack of resources or options. Our problem is largely cultural and historical. Canada’s health care system is by no means perfect. But as we have seen, in their embrace of universality, diversity, transparency and flexibility, their experience could well inform this nation’s next steps.