Do You Know Your Blood Type?

Posted on | March 24, 2025 | 2 Comments

Mike Magee

Medical Science has made remarkable progress over the past 100 years, fueled by basic scientific discoveries, advances in medical technology, improved diagnostic testing, and public health programming to support, inform, and empower patients.

Progress has been sequential, with each new discovery and advance building on those preceding it. These have combined to lengthen lifespan in the U.S. by 70% since 1900. If one were to make a list of the top 10 medical advances in the 20th century, there would be a wealth of candidates, and great debate over which to include. But one candidate for certain would be safe and effective blood transfusions.

In the middle of the 20th century, most Americans knew their blood type. It was one of the earliest pieces of medical data shared with patients. Some of us may still have it enshrined on a Red Cross donor card, or remember learning it in preparation for surgery, as part of obstetrical care, or during hospitalization.

Nowadays, we know a great deal more, data-wise, about ourselves and can refresh our memories by accessing electronic health records. But, surprisingly, blood type is often absent.

Both my wife and I once knew our blood type, but were no longer certain. And blood type is not something you want to get partly right. For victims of major trauma, obstetrical patients, patients undergoing chemotherapy, and aging patients with chronic anemia, blood transfusions remain common.

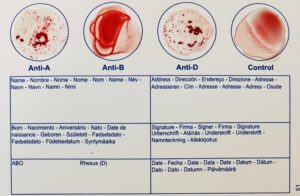

Unlike the past, you don’t need a doctor’s appointment to learn your blood type. My wife and I purchased a self-testing double kit on Amazon for $18.99. My result, A+, is enshrined on the home test card above, delivered in 10 painless minutes. How this was made possible however is part of a complex history that reaches back more than four centuries.

Unlike the past, you don’t need a doctor’s appointment to learn your blood type. My wife and I purchased a self-testing double kit on Amazon for $18.99. My result, A+, is enshrined on the home test card above, delivered in 10 painless minutes. How this was made possible however is part of a complex history that reaches back more than four centuries.

Over 7 million Americans donate blood each year in the United States. Worldwide the number rises to some 120 million donors annually. Together Americans contribute over 12 million units of blood each year. Every two seconds, an American receives a blood transfusion in a hospital, outpatient care unit, or home setting. Each day 30,000 units of whole blood or packed red blood cells, 6000 units of platelets, and 6000 units of plasma are transfused.

For hospital patients over 64, blood transfusion is the second most common hospital procedure. 16% of recipients are in critical care units, 11% in surgical operative suites, 13% in emergency departments, 13% in outpatient units (most in the service of cancer patients), and 1.5% associated with OB-Gyn procedures including 1 out of every 83 deliveries.

Hemorrhage is the most common cause of death in 1 to 40 year olds. In the first hour after arrival at a trauma center, 25% require a transfusion and 3% of victims require more than 10 units of blood. Gun violence is the largest net consumer of blood. Compared to victims of motor vehicle accidents, falls, or non-gun assaults, gun victims consume 10 times more blood, and are 14 times more likely to die in a trauma facility. Massive transfusions themselves carry a significant risk of consumption of clotting factors, acidosis, and hypothermia.

These are the major facts. But how did we arrive at this point in time. Where did the knowledge come from? When did we understand the human circulatory system, and the components and functions of blood itself? Who came up with the idea of transferring blood from one person to another, and how did we learn to do that safely? And who created “blood banks” and why?

An abbreviated history would have to begin with William Harvey who was born on April 1, 1578 in Folkestone, England, and had the good fortune of having the town’s mayor as his father. In his youth, he was described as a “humorous but extremely precise man” who loved coffee and combing his hair in public. He was privileged, curious and studious, a “dog on a pant’s leg” kind of guy when it came to understanding one thing in particular – the human circulation.

Without modern tools, he deduced from inference rather than direct observation (aided by observations and dissections of a wide range of fish and mammals) that blood was pumped by a four chamber heart through a “double circulation system” directed first to the lungs and back via a “closed system” and then out again to the brain and bodily organs.

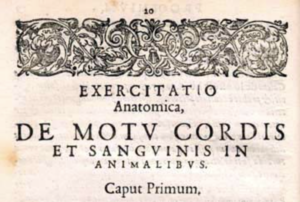

He correctly estimated human blood volume (10 pints or 5 liters), the number of heart contractions, the amount of blood ejected with each beat, and the fact that blood was continuously recirculated. He published all of the above in an epic volume, De Motu Cordis, in 1628. The only thing he didn’t nail down was the presence of tiny peripheral capillaries. That was added in 1660 by Marcello Malpighi who visualized the tiny channels in frog’s lungs.

He correctly estimated human blood volume (10 pints or 5 liters), the number of heart contractions, the amount of blood ejected with each beat, and the fact that blood was continuously recirculated. He published all of the above in an epic volume, De Motu Cordis, in 1628. The only thing he didn’t nail down was the presence of tiny peripheral capillaries. That was added in 1660 by Marcello Malpighi who visualized the tiny channels in frog’s lungs.

All this occurred without an understanding of what blood was. It was only in 1658 that Dutch biologist Jan Swammerdam and his microscope described red blood cells.The notion of possible benefits of transfusions emerged within this same time frame. In 1667, someone tried infusing sheep blood into a sick 15-year old child. The child survived, but not for long. Other animals were attempted as well without success. Over many years other liquids were infused including human, goat, and cow milk, which yielded “adverse effects,” and led others to try saline as a blood substitute in 1884.

The problems with human to human transfusion were threefold. First, between collection form donor to delivery to recipient, the blood tended to clot. Second, there was no way of preserving non-contaminated blood for future use. And finally, the infused blood inexplicably often triggered life-threatening reactions.

Anti-coagulants, like sodium citrate, came into use at the turn of the century, addressing issue number one. The other two issues owe their resolutions in large part to an Austrian biologist named Karl Landsteiner. Through a series of experiments in 1901, he was able to recognize protein and carbohydrate appendages (or antigens) on red blood cell surfaces which were physiologically significant. He defined the main blood antigen types – A, B, AB and O – and proved that success in human blood transfusion would rely in the future on correctly matching blood types of donors and recipients. In 1923, he and his family emigrated to the U.S. where he joined the Rockefeller Institute and defined the Rh Antigen (the + and – familiar to all on their blood types) in 1937. For his efforts, he received the Nobel Prize in Physiology.

Human to human blood transfusions, from healthy to wounded serviceman, proved life-saving in WW I. But the invention of “blood banks” would not arrive until 1937. Credit goes to Bernard Fantus, a physician and Director of Therapeutics at Cook County Hospital in Chicago. A year earlier, he had studied the use of preserved blood by the warring factions in the Spanish Revolution. He was convinced that collecting donated containers of blood, correctly typed and preserved, could be life saving for subsequent well-matched recipients. His daughter, Ruth, noting that the scheme of “donors” and future “lenders” resembled a bank, is credited with the label “blood bank.”

In his first year of operation, Fantus’s “blood bank” averaged 70 transfusions a month. Techniques for separating and preserving red cells, plasma, and platelets evolved after that. And real life tragedies like the Texas City, Texas wharf fire of 1947 with mass injuries tested the system with 1,888 150cc units of pooled plasma administered to survivors of that disaster.

Additional breakthroughs came in response to the demands of WW II. Blood fractionation allowed albumin to be separated from plasma in 1940. Techniques to freeze-dry and package plasma for rapid reconstitution became essential to Navy and Army units in combat. 400cc glass bottles were finally replaced by durable and transportable plastic bags in 1947. And blood warming became the standard of care by 1963. By 1979, the shelf life of whole blood had been extended to 42 days through the use of.an anticoagulant preservative, CPDA-1 and refrigeration. Platelets are more susceptible to contamination and are generally preserved for only 7 days. The components preserved were also prescreened for a wide variety of infectious agents including HIV in 1985.

This brief history illustrates how complex and interwoven, hard-fought and critically important, are the advances in medical science. Empowered citizens today are not only the beneficiaries of these discoveries, but contributors as well. The history of blood transfusion perfectly illustrates this point. If you don’t know your blood type, finding out is a useful starting point, and donating blood remains a remarkable act of good citizenship and a lasting contribution to the health of our nation.

This brief history illustrates how complex and interwoven, hard-fought and critically important, are the advances in medical science. Empowered citizens today are not only the beneficiaries of these discoveries, but contributors as well. The history of blood transfusion perfectly illustrates this point. If you don’t know your blood type, finding out is a useful starting point, and donating blood remains a remarkable act of good citizenship and a lasting contribution to the health of our nation.

Tags: anti-coagulent > bernard fantus > blood > blood band > de motu cordis > hemorrhage > medical discovery > medical history > red cross > transfusion > william harvey

Comments

2 Responses to “Do You Know Your Blood Type?”

Leave a Reply

March 25th, 2025 @ 5:24 pm

“The first systematic description of the movement of the blood came to us from Galen, a famous philosopher/physician who lived in the second century A.D. Unfortunately, it was riddled with errors. ..

Galen’s findings were first challenged in the 1200s by an Arab physician, Ibn-al-Nafiz, who insisted there were no invisible passages from the right side to the left side of the heart and he also correctly traced the pulmonary circulation. But Nafiz’s writings were ignored until the twentieth century, even in the Arab world…”

https://www.aaas.org/taxonomy/term/10/circulatory-system-galen-harvey

Scientists always stand on the shoulders of those who came before them.

March 25th, 2025 @ 7:01 pm

Absolutely correct, Dr. J. Appreciate your highlighting these contributions, and the important tenet of history that many innovations provide the foundation for what is often remembered as the “original discovery.”