Science as a Tool of Diplomacy. The Brief History of Balloon Angioplasty.

Posted on | March 17, 2025 | No Comments

Mike Magee

“Navigating Uncertainty: The recently announced limitation from the NIH on grants is an example that will significantly reduce essential funding for research at Emory.”

Gregory L. Fenes, President, Emory University, March 5, 2025

In 1900, the U.S. life expectancy was 47 years. Between maternal deaths in child birth and infectious diseases, it is no wonder that cardiovascular disease (barely understood at the time) was an afterthought. But by 1930, as life expectancy approached 60 years, Americans stood up and took notice. They were literally dropping dead on softball fields of heart attacks.

Remarkably, despite scientific advances, nearly 1 million Americans ( 931,578) died of heart disease in 2024. That is 28% of the 3,279,857 deaths last year.

The main cause of a heart attack, as every high school student knows today, is blockage of one or more of the three main coronary arteries – each 5 to 10 centimeters long and four millimeters wide. But at the turn of the century, experts didn’t have a clue. When James Herrick first suggested blockage of the coronaries as a cause of “heart seizures” in 1912, the suggestion was met with disbelief. Seven years later, in 1919, the clinical findings for “myocardial infarction” were confirmed and now correlated with ECG abnormalities for the first time.

Scientists for some time had been aware of the anatomy of the human heart, but it wasn’t until 1929 that they actually were able to see it in action. That was when a 24-year old German medical intern in training named Werner Forssmann came up with the idea of threading a ureteral catheter through a vein in the arm into his heart.

His superiors refused permission for the experiment. But with junior accomplices, including an enamored nurse, and a radiologist in training, he secretly catheterized his own heart and injected dye revealing for the first time a live 4-chamber heart. Werner Forssmann’s “reckless action” was eventually rewarded with the 1956 Nobel Prize in Medicine. Another two years would pass before the dynamic Mason Sones, Cleveland Clinic’s director of cardiovascular disease, successfully (if inadvertently) imaged the coronary arteries themselves without inducing a heart attack in his 26-year old patient with rheumatic heart disease.

But it was the American head of all Allied Forces in World War II, turned President of the United States, Dwight D.Eisenhower, who arguably had the greatest impact on the world focus on this “public enemy #1.” His seven heart attacks, in full public view, have been credited with increasing public awareness of the condition which finally claimed his life in1969.

Cardiac catheterization soon became a relatively standard affair. Not surprisingly, less than a decade later, on September 16, 1977, anther young East German physician, Andreas Gruntzig, performed the first ballon angioplasty, but not without a bit of drama.

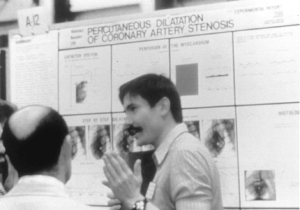

Dr. Gruntzig had moved to Zurich, Switzerland in pursuit of this new, non-invasive technique for opening blocked arteries. But first, he had to manufacture his own catheters. He tested them out on dogs in 1976, and excitedly shared his positive results in November that year at the 49th Scientific Session of the American Heart Association in Miami Beach.

Poster Session, Miami Beach, 1976

Poster Session, Miami Beach, 1976

He returned to Zurich that year expecting swift approval to perform the procedure on a human candidate. But a year later, the Switzerland Board had still not given him a green light to use his newly improved double lumen catheter. Instead he had been invited by Dr. Richard Myler at the San Francisco Heart Institute to perform the first ever balloon coronary artery angioplasty on a wake patient.

Gruntzig arrived in May, 1977, with equipment in hand. He was able to successfully dilate the arteries of several anesthetized patients who were undergoing open heart coronary bypass surgery. But sadly, after two weeks on hold there, no appropriate candidates had emerged for a minimally invasive balloon angioplasty in a non-anesthetized heart attack patient.

In the meantime, a 38-year-old insurance salesman, Adolf Bachmann, with severe coronary artery stenosis, angina, and ECG changes had surfaced in Zurich. With verbal assurances that he might proceed, Gruntzig rushed back to Zurich. The landmark procedure at Zurich University Hospital went off without a hitch, and the rest is history.

Within a few years, Gruntzig accepted a professorship at Emory University and relocated with his family. He was welcomed as the Director of Interventional Cardiovascular Medicine.

As the Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine reported in 2014: “Unlike Switzerland, the United States immediately realized Grüntzig’s capacity and potential to advance cardiovascular medicine. Grüntzig was classified as a ‘national treasure’ by the authorities in 1980; however, he was never granted United States citizenship. Emory University had just received a donation of 105 million USD from the Coca-Cola Foundation (an amount which in 2014 would equal approximately 250 million USD), one of the biggest research grants ever given to an academic institution, which allowed the hospital to expand on treatment of coronary artery disease using balloon angioplasty technology.”

Gruntzig’s star rose quickly in Atlanta. His combination of showmanship, technical expertise, looks and communication skills drew an immediate response. Historians saw him as a personification of the American dream. As they recounted, “The first annual course in Atlanta was held in February 1981. More than 200 cardiologists from around the world came to see the brilliant teacher in action. The course lasted 3 and 1/2 days with one live teaching case per half day and, with each subsequent course, the momentum for angioplasty increased.”

According to Emory records, “In less than 5 years at Emory, Grüntzig performed more than 3,000 PTCA procedures, without losing a single patient.” Remarkably, after 10 symptom free years, Gruntzig’s original patient, Adolf Bachmann, allowed interventional cardiologists from Emory to re-catheterize him on September 16, 1987, the 10-year anniversary of his original procedure. The formal report documented that the artery remained open, and the patient was symptom free.

As this brief history well illustrates, science has historically been a collaborative and shared affair on the world stage. In an age where Trump simultaneously is disassembling America’s scientific discovery capabilities, undermining historic cooperation between nations, and leaving international public health initiatives in shambles, it useful to remember that institutions like Emory have well understood that science requires international cooperation, and not only has the power to heal individuals, but also is a critical tool of diplomacy.

Video: Andreas Gruntzig (in his own words).

Tags: Adolf Bachmann > Andreas Gruntzig > balloon angioplasty > cardiac catheterization > Cleveland Clinic > Dwight D. Eisenhower > Emory University > Gregory Fenes > James Herrick > Mason Sones > Richard Myler > Werner Forssmann

Comments

Leave a Reply