Retail Pharmacy: The Nucleus of the Pharmaceutical Industry. Part 2. Crossing The Pond.

Posted on | September 7, 2019 | 1 Comment

Mike Magee

By the 18th century, in Germany, England, France and Switzerland, says one British historian, “a man practicing pharmacy, whether apothecary or chemist and druggist”, saw his retail operation as the cornerstone of a potential wholesale gold mine.

What is it they produced back then? Well at least in Britain, the answer is, quite a lot of what is affectionately termed today “little technology”. From the same British historian, “Pills and boluses could be made by hand, tinctures by the simple process of maceration or the slightly more complex one of percolation, infusions were more than making a cup of tea, and ointments merely used mortar and pestle. Few chemists and druggists were content with just dispensing, but developed what has been termed their ‘own lines’, that is the pharmacists own formulation for a soothing cough mixture, a worm eradicator, an ointment for scabies, but not too griping purge. Many hoped to make a fortune.”

So in one sense, Mr. Jones’s philosophy of never leaving a penny on the floor, undeveloped, was an inherited value dating back a century or two. These were versatile and imaginative entrepreneurs, experimenters with high productivity, if not uniform quality. One pharmacy in Birkenshaw, Yorkshire, had a handwritten formulary that included 534 discreet formulas – 316 medicinal, 69 cosmetic, 68 veterinary, and 81 “domestic”. Among the lot were compressed tablets, cold creams, lotions, essence of smelling salts, powders of all types, and brandy. But of course, there were other offerings considerably more exotic like cockroach bait, glove cleaner and non-mercurial plate powder.

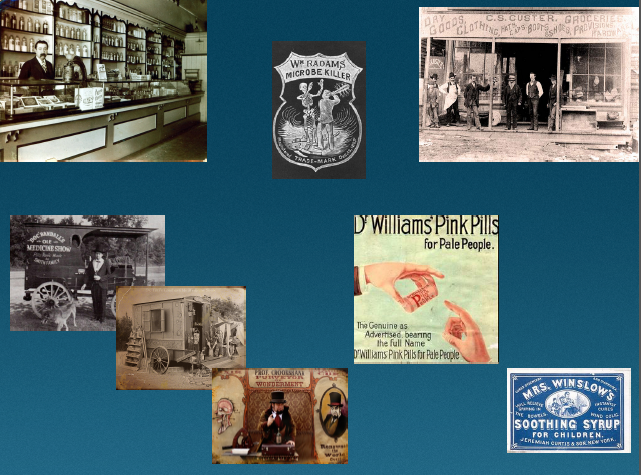

Simple discoveries in delivery systems expanded the market. Cocoa butter introduced in 1852 launched a worldwide surge in suppositories. The soft gelatin capsule opened all new possibilities in 1834. Subcutaneous injections followed in 1855. By then, some medicines were described as patent or proprietary, but most were simple ‘secret formula’ concoctions that were not registered. As one expert noted, “The ‘quack’ medicines would have had little, if any, therapeutic value, but then neither had most of those prescribed by physician or surgeon apothecary; indeed there was often little to tell between them. The ‘patent’ medicine trade at least had the merit of passing on the knowledge of how to manipulate equipment and mix ingredients in bulk.”

These larger scale and more methodical chemists became increasingly prominent in Europe, and to a much lesser extent in America, in the second half of the 19th century. They produced three general types of products – those derived from simple compounds of vegetable substances (examples being ginger or aloes); those generic substances listed in the official country’s Pharmacopoeia, a document of “real medicines” carrying the imprimatur of the country Medical Society (like morphine and quinine); and those that were being developed increasingly according to new industry standards which emphasized systematic chemical research and laboratory development (such as new sera and vaccines).

Prominent as leaders of the 3rd group in 1880 in Britain was Burroughs Wellcome. While London based, it was the brainchild of two American entrepreneurs, Silas Burroughs and Henry Wellcome. Marketers at heart, they were the originators of sales visits to doctors offices and free samples left behind – a practice that would a century later be tangled up in a contentious debate over conflict of interest and direct advertisements to patients themselves.

Flowing in the other direction of Burrough and Welcome were chemists and scientists like German immigrants Charles Pfizer and Charles Erhardt who saw immense opportunity in America as this energetic nation took its first transformational steps into the Industrial Age. Still others, like fellow German immigrant Willliam Radam, saw in America the “Wild West”, and the opportunity to make a killing. And he literally did. Marketing a dilute solution of sulfuric acid colored with red wine, his “Microbe Killer”, widely advertised and sold often in religious/theatrical “fire and brimstone” revival sessions (promising to “Cure All Diseases” – a phrase embossed on its glass bottle), he made a quick fortune. Taken in high doses, it also killed a few people.

Comments

One Response to “Retail Pharmacy: The Nucleus of the Pharmaceutical Industry. Part 2. Crossing The Pond.”

September 8th, 2019 @ 11:15 am

Again, thank you for interesting and useful information. Peace,

Chuck